By Priya Bhattacharji

A daily scroll on social media ensures an encounter with polymaths from various spheres.

It’s impossible not to chance upon hyphenated self-descriptions that express prolificacy. You know what I’m talking about, right? Doctor| Runner| Wanderer| Lover of Life, FilmLover.Father.Fanboy of Techno, Travel, and Tacos– Economical Bios that describe the multitudinous are ubiquities on social network

It’d be exceptionally lazy of me to state that Utpal Borpujari needs no introduction.

He holds an unusually remarkable accomplishment in the field of cinema. In 2003, he earned a National Award for Best Film Critic. Fifteen years later, his debut feature film “Ishu” fetched him the country’s most coveted award, again. A propelling force for the erstwhile neglected cinema from the Seven Sister States, his various pursuits as a journalist, film critic, scriptwriter, documentarian, curator, and filmmaker speaks volumes for his steadfast love for cinema.

We speak to him to know more about his exceptional contribution to cinema, and viewpoints on cinema from the North East:

Your Twitter bio reads: National Award-winning Filmmaker-Film critic. IIT-Roorkee Alumnus. Firstly, filmmaker-film critic. Secondly, MTech in Applied Geology from IIT-Roorkee. Some interesting career oscillations, or gradual progressions, to speak about.

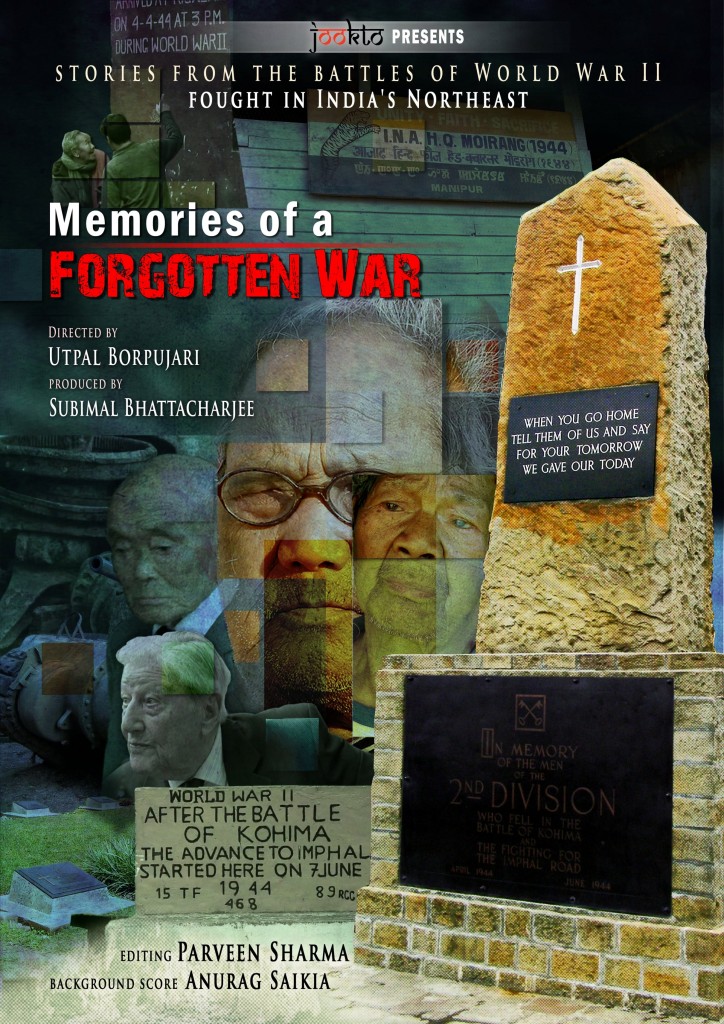

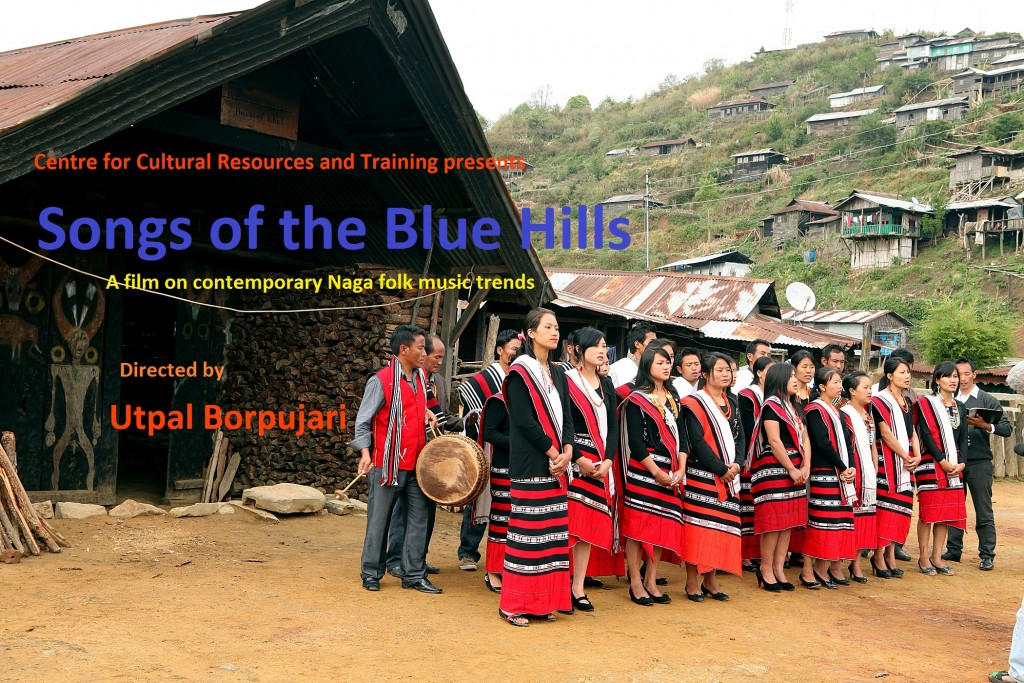

The answer is simple – if one is passionate about cinema you invariably explore its various facets. I started watching films at an early age at the screenings and festivals of Assam Cine Art Society (ACAS), a film society in Guwahati. You could call that experience ‘serious watching’ as it acquainted me with various kinds of cinema. Then when I started as a freelance journalist, I wrote on culture, cinema, politics: the view became more serious, more analytical, an academic pursuit where you study cinema as an art form. In 1994, I shifted base to Delhi, where I was exposed to a wide spectrum of cinema and viewing experience. Apart from attending various film festivals – the IFFI used to be held in Delhi back then, and there used to be the Osean’s Cinefan Film Festival that is no longer held, there are some cultural centres – India Habitat Centre, Hungarian Cultural Centre, Max Mueller Bhawan, the British Council, Italian Cultural Centre, etc., where I regularly watched films. In 2003, when I won the National Award for Best Critic I felt what I was doing was right. Towards 2010, I wanted to start making films as I felt there was a lack of space in print media for certain subjects and issues about the North East that I wanted to talk about. I couldn’t get to write and talk about them the way I wanted to as a journalist working for a publication. That led to my first documentary in 2012 – Mayong: Myth/Reality. Before I got to make my first feature Ishu, I made four more documentaries (Songs of the Blue Hills, Soccer Queens of Rani, For a Durbar of the People, Memories of a Forgotten War). As a filmmaker, my work deals with untold stories – something my work till then could not deal with earlier as a journalist. They aren’t films that are merely based in Northeast India but about incidents, practices, and people about which little is known or written about.

What about curating?

It comes naturally, I’d say. As a critic, you are used to watching 4-5 films a day, so selection becomes a natural after-process. As a filmmaker, you tend to look for subjects that are lesser known and can resonate widely. As a result, I got into the role of Curator/Consultant for various Northeast-centric programming at numerous editions of the IFFI. I also worked as the Artistic Director of the now-defunct Guwahati CineASA International Film Festival, which started in 2009 but got discontinued after 7 years because of lack of funding. Recently, I got associated with the Pondicherry International Film Festival, which had its first edition in 2018, as an advisor.

As a film critic, what was your approach of analysis? What do you have to say about the current state of film analysis?

With the Internet, writing about cinema has been democratised in numerous ways. Some of the new critics who write online write very well and in depth. You no longer need a column in a newspaper to write about cinema. Not only are there more avenues to write about it, but there are also several points of views, tones, and styles to write and discuss cinema, along with other content that’s widely available.

For me, writing about cinema, first and foremost, it is to look at it as an art form – above the science and commerce that are invested in it. Cinema has and will be remembered for the art in it – the art of storytelling, how it explores visual storytelling, how it captures the changing facets of society. I think that’s where the lasting impact of cinema lies. To me, it is reading and understanding a human document.

In the past five years, there has been a lot of talk about “Cinema from the North East”. What I find fascinating are the fine examples of independent filmmaking that have come from the region – Village Rockstars, Local Kungfu, besides the independent ‘superstar’ Adil Hussain.

See, only two states of the North-East have had long cinematic journeys. The first Assamese film, Joymoti, was made in 1935. Manipur had its first in 1972 (Matamgi Manipur). As for the rest of the NE, cinema is not dominant as communities are small. In a state like Arunachal Pradesh, tribes range from 5000-50,0000. As an ethnically diverse region with many dialects, it is hard for films made in one region to find wide audiences in other parts of the North East because of linguistic barriers. Unless it has subtitles, a Khasi film might not make sense in Manipur. Why Manipur, it would not make sense even in the Garo Hills district of Meghalaya itself. Making or distributing cinema has not been commercially sustainable in the region because of the limited commercial prospect arising out of this fact.

But what is happening in recent times is quite interesting: a new kind of cinema has emerged in the region – films that are shot in the Northeast with the intent of building a universal appeal. The hope is that once the film passes the borders of India, it will sail. Apart from the films you mentioned – Kothanadi (Assam), Loktak Lairembee (Manipur), Crossing Bridges (Shertukpen dialect of Arunachal Pradesh), Onataah (Khasi, Meghalaya) are examples of stories and storytellers rooted to their soil yet universal in nature. They have travelled far and wide to festivals worldwide and online platforms and in some exceptionally fortunate cases, got a theatrical release. I suppose the general idea is to make films about subjects that are personal and treat them in a way to get noticed by uninitiated audiences.

What about the ecosystem for both mainstream and independent films to be accessed within the region?

It’s been the lack of screens that have hindered the widespread distribution of films. The topography, the political climate, the presence of many languages and dialects has resulted in limited screens. The traveling cinema model that is in existence in parts lacks commercial prospects. However, things are changing. Local people and organizations and various platforms outside of NE are trying to do something out of the box – for example, the platform 1018mb.com took ‘Local Kungfu 2’ to other cities outside the region. A few other films have also got commercial screenings in various parts of India like this. Films from the region are also getting onto various OTT platforms.

Guwahati has had several film festivals and film societies. The Assam government has in recent times announced incentives for the revival of local cinema. The Guwahati international Film Festival, for example, is in its third year of running. The last edition had more than 100 films from 50 countries showcased that ranged from children’s cinema, animation to short films. Then you have the Adda Short Film Festival and the Brahmaputra Valley Film festival which are specifically serving as platforms to showcase films from the region. The Assam government recently also started the Guwahati International Children’s Film Festival and the Guwahati International Documentary and Short Film Festival, which have had very good response from the public.

What makes you enthusiastic about cinema from the North-east?

In the last three-four years, it has seen several quality films made by young, upcoming filmmakers. Every year I have had the chance to watch at least 8-10 good short films, made by first-timers or college students. Most of them are films about local stories or are based on short stories from the region. Also, with spaces opening up for domestic distribution, with increased connectivity the growing penetration of Amazon Prime and Netflix in the region holds hope for local films to be consumed within the region – one that makes commercial sense for the filmmakers and gives audiences a chance to watch films made about their region and culture.

Tell us something about your feature ‘Ishu’.

It is a film based on a novel by noted writer Manikuntala Bhattacharjya and produced by the Children’s Film Society, India. It reflects on a grim social issue – witch-hunting – which is practiced among certain communities in Assam and Meghalaya. Through the eyes of 10-year-old, the film offers insight into this despicable practice. Besides winning a National Award and a special Jury Award at the Bengaluru International Film Festival, it has won several honours in the Assam State Film Awards. It has also travelled to a number of international film festivals. However, what I am enthused about is that it got a very good response in a few screenings that were organised in rural parts of Assam. I am looking forward to taking the film to rural Assam extensively soon. I feel the film will serve a purpose if it travels to the places it draws inspiration from and can connect with the people it wishes to talk to.

You know “social” and “political” have become trendy terms in mainstream Hindi stream. Coming from a region of political unrest, an experience of understanding, sieving, and creating socially charged cinema, what are your views?

There are no real political films in India, barring a few, in recent times. What currently exists are oblique commentaries or propaganda. I see no quality political films. I mean you forget them after one viewing. Artistically and theoretically, there is nothing for the audience to retain. It’s not that quality socio-political films have never been made – there have been films by Govind Nihalani, Shyam Benegal, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, G Aravindan, et al. that are a far cry from the ’political’ films of today. The political chaos naturally tinges films from the North-east, so there is always a socio-political context in most films. I find Pradip Kurbah’s Ri — Homeland Of Uncertainty that looks at insurgency and reconciliation in North-East India a good example among recent films. Not only did it fetch a National Award, but it was this rare Indian film that was adapted into a book. I feel current mainstream political films tackle issues in a wishy-washy manner. Some of these films have been a commercial success. Apart from the immediate box office aspect, will these films be remembered, cited as commentaries or viewpoints, or generally stand the test of time – I’m not convinced.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.