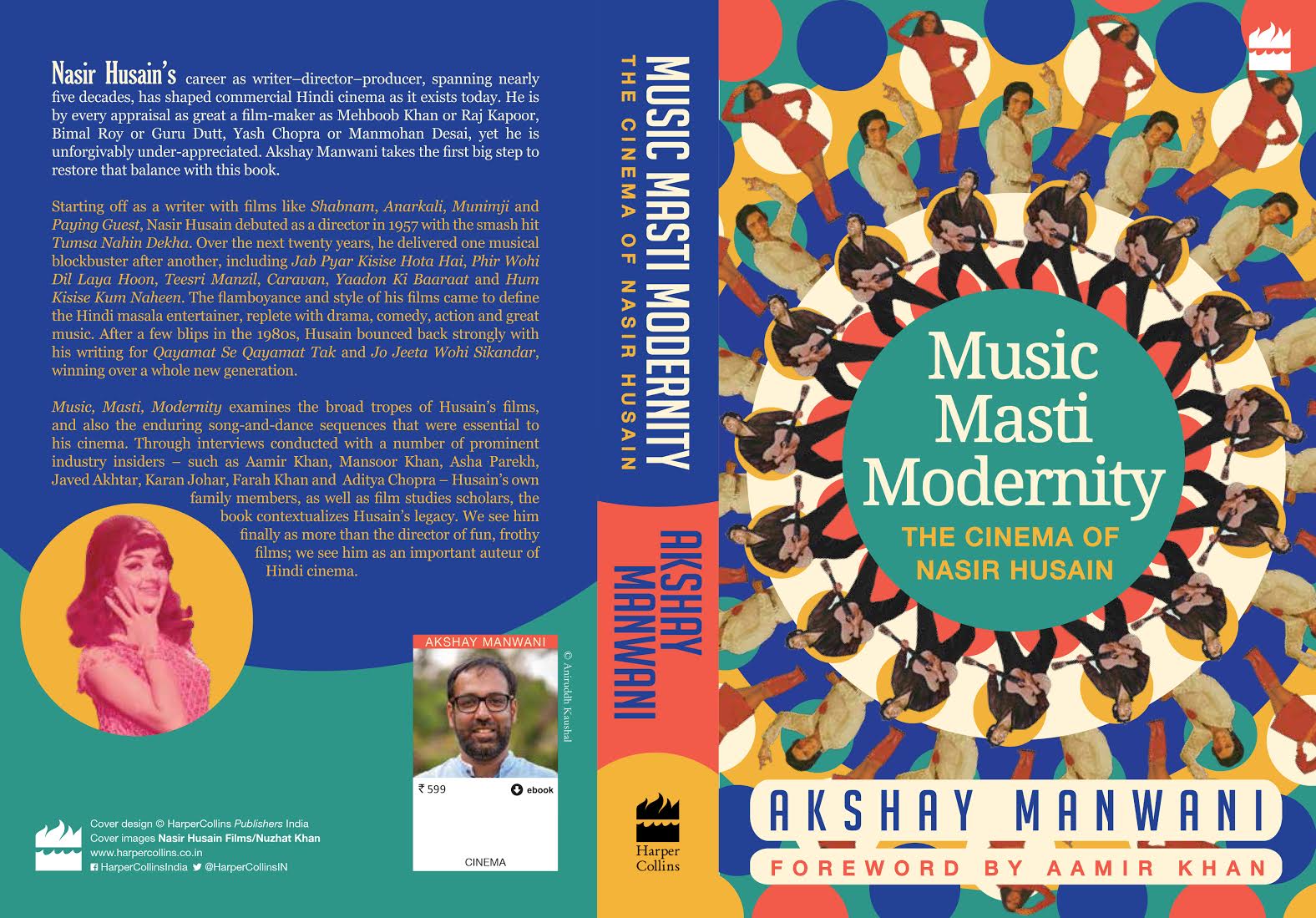

After his first, Sahir Ludhianvi: The People’s Poet, writer/author Akshay Manwani is back with his sophomore cinema-specific book: a thoroughly compiled, non-celebratory and informatively balanced exploration of the career of writer-filmmaker Nasir Husain, aptly titled Music, Masti and Modernity: The Cinema of Nasir Husain.

Published by HarperCollins India, the 402-page book is available for purchase online and in stores.

Here is a fascinating excerpt from a book, that is as much a well-informed, detailed critique as it is an analytical argument of Husain as an important Indian auteur far too underrated in his time:

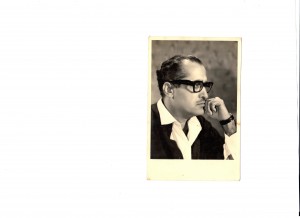

Image courtesy: NH Films

Hindi films of the late-1940s right up to the mid-1950s had the hero and heroine fall in love almost instantly. There was no elaborate courtship between the film’s protagonists. The narratives concentrated on what happened after the film’s protagonists fell in love or the obstacles that came in the way of realizing their romance. There were exceptions like Aan (1952), Mr. & Mrs. ’55 (1955) and Chori Chori (1956), but such films were few and far between.

In Dev Anand’s Ziddi, for instance, his character and Kamini Kaushal’s character are shown to fall in love and talk marriage within the first twenty minutes of the film. In Awara, Raj (Raj Kapoor) and Rita (Nargis) fall in love with each other the moment they realize they were childhood friends. Filmistan’s Nagin was perhaps the most bizarre. Here, two ethnic communities are locked in enmity for several years when the film begins. Against this background, Mala (Vyjayanthimala) and Sanatan (Pradeep Kumar), the respective successors to both clans, make grand declarations of heaping more misery on the other community at the start of the film, but take precisely seven cinematic minutes from their first acquaintance to fall in love.

This instant romance irked Husain. He told Nasreen, ‘One thing I did not like about the films in those days was that in all the films there was this usual scene that the hero is sitting and the heroine comes from behind. She then puts her hands on the hero’s eyes and asks, “Bolo main kaun hoon? (Guess, who?)” I don’t remember how many times I had seen this scene. Bezaar ho gaya thaa main. (I was completely frustrated.) I wanted to do this in a more modern way.’

He did. For him, the wooing was an important part of his narrative. ‘It’s the process of falling in love that’s more exciting than the romance itself,’ he said. He would have the lead pair acquainted early in the film, but with the hero (always) initially irritating the heroine with his demeanour or tricks. The heroine would resist the hero, even loathe him, but only until he rescues her from a tricky situation or has built up empathy in her heart through one of his ploys (such as terminal illness) after which she reciprocates his affection.

Although this can be seen in Munimji and Paying Guest, it is in Tumsa Nahin Dekha that the romance between Meena and Shankar played out for a far longer duration. Bear in mind that in Munimji, Roopa has fallen for Raj before the halfway mark in the film. Something similar happens in Paying Guest, where Shanti and Ramesh sing the wonderful duet ‘Chhod do aanchal zamaana kya kahega’ just after the forty-five-minute mark. In both films, the storyline takes a different turn once the romance between the protagonists has been established.

Tumsa Nahin Dekha is different. Here Meena and Shankar come into contact quite early in the film. But it isn’t until late in the second half, after Shankar has rescued Meena from being held hostage by Bhola, that Meena has a change of heart. Before that, the two are at loggerheads, beginning from the time that they meet at the station and, by sheer coincidence, share a train journey while making their way to Ghatpur. Their constant bickering, moments of madness and battle of wits, even through a song, ‘Aaye hain door se’, make Tumsa Nahin Dekha a fun film. Take the exchange the two have immediately at Soona Nagar station, fighting for the only tonga available that can take them to Ghatpur, with a hapless tongawallah caught in the crossfire.

Meena: Aye, aye! Yeh taanga mera hai. Tum ismey nahin ja saktey. (Hey, hey! This is my tonga. You cannot take it.)

Shankar: Kyun nahin ja sakta? Aapse pehley mera saamaan pahuncha hai. (Why can’t I? My luggage was loaded on it before you reached.)

Meena: Taangeywaaley, mera saamaan rakho. (Tongawallah, load up my luggage.)

Shankar: Taangeywaaley, khabardaar! Agar inn madam ka saamaan iss taangey mein rakha toh tumhaari yeh lambi moochhey ukhaad loonga. (Tongawallah, beware! If you place this lady’s luggage in the tonga, I will rip your long moustache off.)

Taangeywaala: Yeh kya kar rahe hain, huzoor? Jhagda aap dono ka hai aur dushmani meri moochhon se? (What are you doing, sir? Why direct your ire at my moustache when it is the two of you fighting?)

Shankar: Aisa hi hoga. Military mein reh chuka hoon pyaare, pehla waar moochhon pe karta hoon. (That’s how it is. I have served in the military, my dear, I always attack the moustache first.)

Meena: Sahaab military ke hajaam thay. Tum iski fikra na karo. Mera saamaan rakho warna tumhaara keema nikaal diya jaayega. (The gentleman was a barber in the army. Don’t you worry about him! Load my luggage or I will make mincemeat of you.)

Shankar: Ha ha, memsa’ab ki gosht ki dukaan hai… (Ha, ha, the lady appears to be a butcher…)

[Meena cuts Shankar off by lunging for his throat.]

A similar banter between the hero and the heroine played out pretty much in each Husain film. The nok-jhonk between the protagonists kept the audience riveted. The hero’s puckishness matched the heroine’s feisty, will-tolerate-no-nonsense attitude and formed the bulk of Husain’s narratives. ‘Add to that good music, a lot of humour and the audience enjoys it,’ Husain said.

The crucial point here is that Husain didn’t patent the lengthening of the wooing process. It is his style that was different. Films like Albela (1951), Dholak (1951) and Mr. & Mrs. ’55 had already started breaking from the mould. However, in these films, the onset of romance happened on a slow boil. It wasn’t until much later in the film that the crucial admission of love happened.

In Husain’s films, the hero almost immediately falls in love with the heroine. The heroine hates the sight of him initially only to have a change of heart midway or closer to the film’s climax. ‘The “hate” or “pretend hate” is not mutual, as in the other films,’ noted Madhulika Liddle.

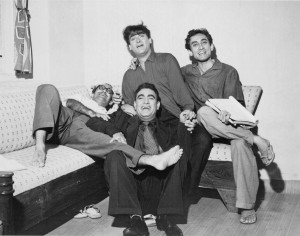

Image courtesy: Rauf Ahmed

According to Rauf Ahmed, ‘He wanted to make the hero bold and aggressive. The hero would have to really fight for her. He will sing and dance. He will not be ashamed of himself. The earlier concept was that singing and dancing were all for women.’ But Rauf also recalled Shammi’s complaint with this elongated courtship approach pursued by the hero: ‘Shammi Kapoor would say, “Yes, I will have to fight for her, but by the time I win, the villain comes. I don’t get any time with her.”’

But Husain did give his protagonists a few tender moments together. In Jab Pyar Kisise Hota Hai, when Sunder (Dev Anand) and Nisha (Asha Parekh) spend a day out in Neelgaon’s idyllic environs, Nisha asks Sunder, ‘Kahiye, dekhi hai issey zyaada khoobsurat cheez? (Tell me, have you seen anything more beautiful?)’ Sunder responds in the affirmative. When Nisha says he is lying and asks where he has seen such a place, he responds, turning to Nisha, ‘Jab gardann ghumaata hoon, dekh leta hoon (When I turn my head, I see it).’ Husain also used poetry in such moments as seen from his dialogues across films. This ability to build romance with a certain delicate touch is what ultimately helped Husain bounce back at the fag end of his career.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.