By KENNY BASUMATARY

Whew.

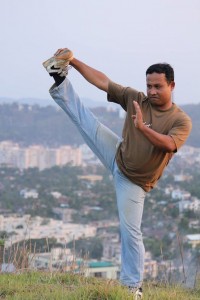

Starting with a production budget of Rs 95,000 (believe it), it’s almost unreal that (arrogant though it may sound) it seems like almost every young person in Assam has seen my first feature film, the martial-arts comedy, ‘Local Kung Fu’, by now. I go there just a few times a year, but my friends and family who acted in it are constantly recognized wherever they go. I’m really happy for them; I couldn’t pay them anything beyond peanuts, so at least fame is proving to be some form of remuneration. I myself didn’t gain financially from the film, but it opened a lot of doors and led to a couple of very decent gigs – which were lucrative enough to not have time to think of a second feature for a while.

But now that the time is here and I need to write something intelligent-sounding for this website, I thought I would write about what I would do differently if I had to do it again and what I wouldn’t.

The first one will probably be of some use to people undertaking the foolhardy journey of making their first film, and the second one is for myself so that I don’t lose track of the basic things that should never be forgotten. I’ve learned it the hard way, even though the outcome was more satisfactory than I could have ever imagined.

THINGS I’D DO DIFFERENTLY

1. Get a trained camera person

NEVER compromise on such technicalities, just because it’s the DIY brand we’ve embraced. This would’ve saved a whole crapload of heartburn and being on the learning curve for a long time. I did look for a DoP, but I wouldn’t have been able to pay them an amount that would enable me to look them in the eye with some amount of self-respect, and secondly, there was no way we could operate on a fixed schedule. Out of our 95k budget, 58k was for the Canon 550 D, a lens and accessories, and a considerable chunk for momos, noodles and rice cakes. As for scheduling, we would co-ordinate one cousin’s drum class, another’s tuition and a friend’s office or school schedule and shoot whenever depending on whoever was free. Being unable to hire a pro camera person, I started learning from Guru Youtube about composition, lighting, lensing – whatever I could. Among the first scenes we shot was the sparring between the two main villains. This was shot in broad daylight with the sun burning out all the highlights, and I had no idea what to do about it (embarrassing to admit it now). Later I learnt about shutter speeds and apertures, and adjusted accordingly. Needless to mention again, a pro DoP would’ve really helped here.

2. Have someone handle costumes and art – preferably someone with a good sense of aesthetics

My sense of production design was limited to reading somewhere that white walls are very boring, and therefore sticking DC comics posters on the walls of what would be my character’s room.

3. Have an all-rounder assistant

To worry about scheduling, food and transportation, storing footage, charging batteries, and to remind you of things you might have forgotten, like an reaction shot or a bit of dialog. A multi-tasking all-in-one Man Friday is of prime importance.

That makes it a crew of 4, which in practical terms means you need to have access to a car or two bikes. Well, you can make it even as a crew of one, like I did, but having these three additional people will reduce headaches tremendously. (The day I had only a bike, I wore the huge bag with the fighting gear in front and the camera bag on my back.)

4. Don’t drag out the schedule over too long

For the final fight, we shot the reaction shots in November and the actual fight in May-June. Now, no one actually notices this, but the walls of the school where we shot had peeling old paint in the November shots and fresh paint in May-June. Obviously we couldn’t tell the school not to get a fresh layer of paint. Not just that, within the same scene, my cousin Jonny’s hair length goes from long to short to long to short. A corollary to this also is: don’t work non-stop.

THINGS I WOULD DO AGAIN

1. Edit on set

I didn’t edit on set, but for the fight scenes, I would convert the footage to very low-res wmv files and edit them on Windows Movie Maker on my cousin’s 128 mb RAM desktop! This was invaluable to make the fights work, because we could see what was working and what wasn’t clear, and reshoot soon after. It’s one thing to visualise certain sequences and actions, and another to execute and seamlessly stitch them together. I can think of at least one very important elbow strike which we shot this way – because without it, a fighting transition wasn’t making sense. I also favour editing soon after shooting, so that the memory of good takes and moments is fresh. Furthermore, there are things one sees on a monitor that one doesn’t notice on a small camera display, such as a non-actor furtively glancing at the camera.

2. Don’t be in a hurry

Our shooting days weren’t chock-a-block with 6 am to 6 pm schedules. It was more like – okay, in the morning, we’ll go to Flower Lane and shoot the fight with Gobinda and Bimal, then in the afternoon, we’ll pick up Deepa and go to Bob’s place to shoot the scene with him. This really really helped because we had some freedom to relax and come up with new gags on the spot that might not have been there at the scripting stage. For example, in the Flower Lane fight, Bonzo hides behind a stack of bricks that we didn’t know was going to be there. But even then, it’s important to respect people’s time and not have them waiting around or delayed. And over and above all this, it is also about whether you can afford the time. I wasn’t paying anyone on a daily basis – no light boys, no drivers, hell, not even a camera vendor – so I could afford to take my time. Things would be quite different if we had the resources only for, say, 20 days, so one needs to find out where to compromise.

3. The characters should be in a hurry

In formal terms, actors and writers call this “urgency”, and it’s intricately linked to “energy”. For several scenes, I very consciously had the characters needing to be in a hurry to do something or get somewhere. Importantly, I think one reason ‘Local Kung Fu’ works is that the main characters have very clearly defined wants. Charlie wants to patao his girlfriend’s family, Dulu wants the liquor license, Bonzo wants to be the number one under-18 don (which morphs into wanting to bash up Charlie). Any time I set out to write something, this is the first thing I try to figure out (and I’d better never forget this): what do the characters want? Their wants are what will drive everything in the story. The simpler, the better.

4. Take a long time to edit

From the time I had a complete first cut to the time I submitted the final cut to Scrabble for the PVR release, it was about a year. Over the course of that year, I showed the film many times to many people – at home, at my brother’s workplace, to solitary people, to small groups of people. And I would always sit at the back and watch their cheeks. People’s cheeks go up when they smile or laugh. More than any kind of feedback people gave, their cheeks were the best barometer of how they were receiving the film, along with other subtle bits and pieces of body language – shifting in their seats, stifling yawns, etc.

It was this unspoken feedback that helped me recognize which parts of the film needed trimming, and which gags might need to be recut. After a year of editing and screening and chopping and changing, the film finally had a pace that didn’t have any lagging bits, at least in my opinion. I have also noticed a curious thing: a film always seems to be be faster when the audience is larger. I guess even if a joke doesn’t work for one person, it works for another, and that sustains the overall energy of the audience.

One of the big advantages I had while making Local Kung Fu was that I had no idea of just how huge a task I was getting myself into. Ignorance was indeed bliss at the time. If I’d known everything that I know now about what goes into making a film look and sound professional and polished, I might never have even started – paralysis by analysis. I only knew a few basic things about camerawork, I had an editing software that couldn’t handle action scenes more than 30 seconds at a time, and I was only thinking of an online release. I took it one day’s work at a time, one shot at a time, one fight move at a time. After all, we did have all the time in the world.

I had no idea about the seven stages of paperwork hell that I would have to go through to secure a theatrical release. That deserves a separate chapter. But in the end, it all worked out when the first major validation came – with acceptance into the Osian’s Cinefan Film Festival. Later, thanks to Shiladitya Bora, then at PVR Director’s Rare, the film was released in 6 metros across the country.

Oh, and the most important lesson of all, which I realized long ago and must remind myself of: NO ONE GIVES A @#$% ABOUT THE STRUGGLE! And neither should they.

As an audience member, I myself don’t care how much trouble someone went through to make something. The only thing I care about is whether I’m engaged or bored.

(The author is an Indian writer & director, and has acted in TV serials, commercials and films like SHANGHAI and MARY KOM. You can watch his whacky martial-arts comedy ‘Local Kung Fu’ here.)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.