By Sushma Khadepaun

A few summers ago, I was the definition of cool – a single filmmaker at an Ivy League University, living in a studio in New York City. (This could very well be the bio of a character from “Friends” or “Sex and the City”)

One evening, I met a friend who was visiting NYC and wanted to know all about this cool life I was leading. Knowing a little bit of my background, she thought she was hanging out with the newly liberated, divorced Indian woman in her thirties who no longer gave a f*ck about the traditions she grew up with. She said to me filled with pride – “You’re the one who ‘got out’”- referring to my rather humble and conservative small-town upbringing. I stared at her blankly, in return.

The truth was, that summer I was ridden with anxiety. I was lonely and broke from making a short film with rent money. The shoot was a disaster and I ended up in the Emergency Room after a panic attack at 4am. I walked to the ER myself. I couldn’t call home, because that would mean my parents would flip out and I didn’t want to give them any opportunity to summon me back to India. It was enough that I was a single, divorced woman in my thirties choosing my own life. I wasn’t allowed to have bad days on top of that.

So, here I was 36-hours later, sitting across from a friend who thought of me as the liberated woman. But I felt caged. And the most frustrating part was that the cage had no lock. No one was holding me at gunpoint to live this life. So why couldn’t I just get out? Why wouldn’t I go back to India? It was home. But was it home? Naguib Mahfouz, the Egyptian Nobel laureate says “Home is not where you are born; home is where all your attempts to escape cease”.

Growing up in Gujarat, it was hard to miss the “foren returns” (expats) – anyone carrying bottled water (Bisleri), men wearing cargo shorts with a t-shirt that read “I <3 <place any-American-city-here>”, people who used English words in every Gujarati sentence or those that used a hand-sanitizer. (pre-COVID, hand sanitizer users were an exclusive NRI club.)

The idea of going away to “foren” – as we say in Gujarati – for a better, more independent life is something of a preoccupation of mine for a long time (No prizes to guess why). This concept, that in order to live one’s best life (sometimes, simply to live a life), one should go far away from home, from everything that’s familiar and comforting, feels bizarre. Yet it is a reality for so many women and a dream for many many more.

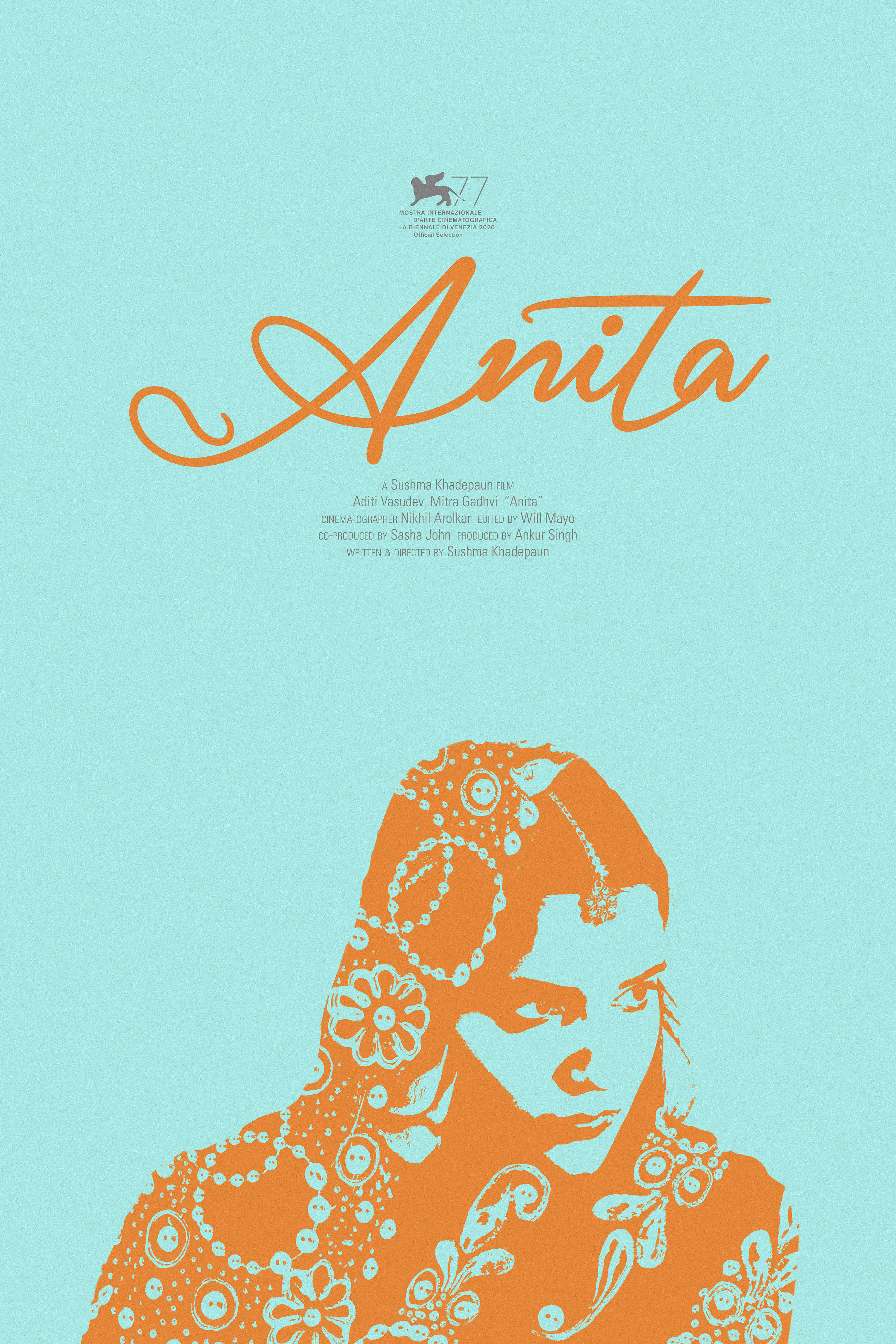

In my recent short film, “Anita”, I dare to explore this idea of a woman returning home after getting the taste for a more “liberated” life. Through this short, I question: is it really possible to “get out” of years of conditioning? Leave behind the misogyny, the patriarchy we grow up with? Or do we find ourselves clinging to what’s familiar, even if the familiar is toxic?

The film offers no easy answers.

In a future, feature version of this short, titled “Salt”, I hope to examine if this escape to another country is a solution at all. And what do you do if you find yourself trapped in your own escape?

As I look up from my computer, I find myself staring at a picture of Virginia Woolf on my desk. I am reminded of a quote by her “As a woman I have no country. As a woman I want no country. As a woman, my country is the whole world.”

[Anita has been selected in the short film section of the 2020 Venice International Festival. It is the only Indian short in the line-up, and the first-ever Gujarati film to qualify for Venice.]

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.