By Rahul Desai

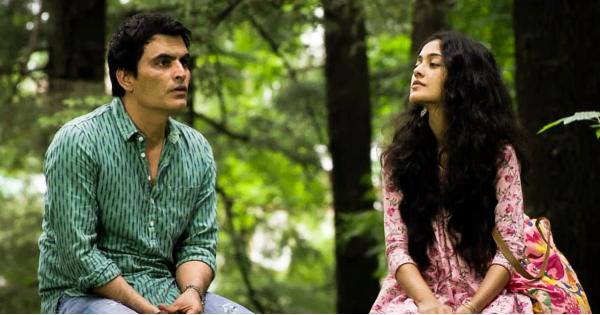

On first impression, Sarthak Dasgupta’s Music Teacher emerges as a tender tale about waiting. Or its more romantic cousin: longing. A middle-aged, Shimla-based music teacher pines for his now-famous student, who had left the Himalayan town eight years ago to become a Bollywood playback singer. Beni Madhab Singh (Manav Kaul) is presented as a man in the valley. He remembers Jyotsna (Amrita Bagchi), the talented Bengali girl whose voice – and heart – he had fine-tuned on a younger mountain. He remembers the day she asked him to quit smoking. The morning she enthralled the judges. The evening she hugged her Beni da.

Everyone thinks Beni is waiting for his Jyotsna. Even Beni thinks he is waiting for his Jyotsna. We feel for the aging mentor and his muted resentments. We empathize with his dignified silence. We root for his unloved neighbour, Geeta, to rescue him with her affection. But look deeper, and there is more to Music Teacher than his sad magnanimity.

What perhaps defines this film is its acknowledgment of modern loneliness as a derivative construct. Manav Kaul’s tortured turn paints loneliness – longing, abandonment, closure – as a ruse for those who cannot tolerate their own failure. This is not a story of a waiting man; it is the story of a man who embraces the romanticized notion of waiting in order to hide under the weight of unfulfilled adulthood. He waits not like himself, but like the sad hero of the screen or the old loner of literature; he even speaks to himself, stylishly chucks away his cigarette and drinks at a bar like a man who views – exploits – isolation as more of a performative artform. A man who fools himself, and his watchers, into believing that he is the victim. The martyr.

In Shoojit Sircar’s October, Varun Dhawan’s Dan subconsciously uses love as a similar device. He cares for a comatose girl as an escape from his own inadequacies; he builds castles in his mind to escape the dungeon of his own incompleteness. Just as Dan turns to an unresponsive Shuili to disguise his lack of maturity, Beni turns to a story of an absent – and unresponsive – Jyotsna to justify his mediocrity. To the film’s credit, this isn’t immediately apparent. The filmmaker beautifully intersperses the narrative with Beni’s eight-year-old memories in a way that lets his dormant persecution complex slowly dawn upon us. He lives for so long with his own guilt that it metamorphosizes into a projection of the rumours that plague his town; he, too, begins to believe that he was betrayed. In fragmented flashbacks, we see that he was once an aspiring singer who failed to make it in Bombay. The death of his father might have forced him to return, but one senses it was also the perfect excuse for him to “sacrifice” his lofty ambitions. Jyotsna, in fact, falls in love with the image of that man.

A devastating scene at a waterfall shatters this image. He tutors her, leading her to win a contest that hands her a major industry contract. When she offers to give it all up, Beni’s eyes acquire the fire of a father who is desperate to live his dream through his unprepared child. In a moment that truly unmasks him, he requests her to aid his career once she is there. “Ask the producers to hear my tapes,” he sheepishly whispers, breaking her heart so loudly that his farewell is barely audible to her ears. Perhaps Jyotsna sees poetic irony in the act of a teacher who wants to use a playback singer – an artist whose voice is borrowed by actors – to broadcast his own voice to a tone-deaf world. In his head, and by extension the heads of those who surround him, a privileged Jyotsna is lip-syncing to his words.

His delusions are visible to those familiar enough to recognize them. Beni’s childhood friend, a no-nonsense politico, is the only one who can see through him. He notices how, once Jyotsna is slated to grace Shimla as a superstar, Beni feels obligated to resurrect his image. He cringes at how Beni, spurred on by his phantom reputation, seems to be persuading himself of an undying love.

When the two finally meet, backstage in the green room, with vanity mirror lights separating their reflections, Manav Kaul’s body language exudes the aura of a loner who has been consumed by a makeshift personality. He expresses his desire to leave, and live, with her. But Jyotsna, like all those years ago at the waterfall, still looks heartbroken. Maybe she senses that Beni da, again, isn’t here for her but for himself. He does not try hard. “Waiting for you has been beautiful,” he concludes. She senses that he is not here to be accepted, but to be rejected, so that his story achieves the circularity of renouncement. So that he can preserve an image of hers – of being the leaver and not the lover – that spares him the ignominy of being the loser.

Beni walks away, somewhat relieved, equipped with an excuse that exempts him from life’s ratrace. His performance is complete. Because, you see, he waited. Long enough to become a tragedy. And nobody questions the sanctity of tragedy. Nobody doubts the mess of a sufferer. Nobody expects a dead man to sing.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.