By Rahul Desai

Devashish Makhija has been around. Some of us have been following this journey, subconsciously even. After watching a couple of good shorts by him over the last few years — some of which I hoped would be translated into full-length dramas — I learned that he was finally making his micro-budget feature-length film. His assistant, Arun Fulara, documented the making of this film in a series of informative, difficult articles.

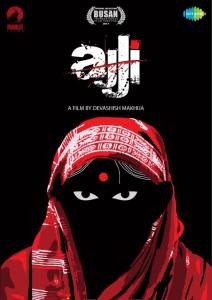

AJJI will compete at the Busan Film Festival and the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival, and has its Indian premiere at next week’s JIO MAMI MUMBAI FILM FESTIVAL 2017.

I spoke to Makhija at length after an early screening of AJJI. He opens up about the experience and about the conversation he hopes to have through his film:

Usually when we think of rape-and-revenge thrillers, it’s either a mother or someone “young” as the wronged protagonist. A grandmother here — how did you get *that* idea?

DM: I have always wanted to tell a story where I take the weakest link in the social chain, put that individual in a situation where the odds are stacked the highest against them, take away every possible crutch/convenience/privilege from that person, and then see how they can achieve what the story needs them to achieve. With ‘Ajji’ I got that opportunity. In a family with a girl, a boy, a father, a mother, a grandfather and a grandmother, we wondered – who is the LEAST likely to be able to take something as dramatic and difficult as revenge. The answer is obvious.

AJJI is the fifth film this year alone in the genre (rape-revenge) in Hindi cinema. Yet the other four (Kaabil, Mom, Maatr, Bhoomi) are unmistakably mainstream, and most filmmakers here consider the ‘vigilantism’ tone distinctly heightened to play on public sentiment. But AJJI is different, and perhaps the most “practical” in terms of its possibility and setting — and hence very uncomfortable. Was this always a conscious choice?

DM: Always. My single-minded intent with this film was to take an archetypical character journey (rape – revenge to be specific) so the viewer would have preconceived expectations of the story, and see if I can subvert those expectations. It’s a very different challenge, this – to take a formula and undo it piece by piece.

The ‘practical’ you speak of comes perhaps from my obsession with exploring the helplessness of individuals who are deprived of opportunities…marginalized by the ‘mainstream’…disenfranchised because of inequalities. Ajji is one such individual. She is a woman in a fiercely patriarchal social framework. She is poor in a city that celebrates wealth as an indicator of a better life. She is frail in a world where the rules are made by those with brute strength. And she is ageing. She is ‘unequal’ in every way. And watching someone like her ‘take on’ forces beyond her capacity will always be uncomfortable, simply because if the fight seeks to be ‘authentic’ she most probably will NOT succeed.

Does it say something about the country’s current climate that this concept is suddenly a cinematically prolific one?

DM: Yes. Stories must reflect the zeitgeist. Otherwise what’s the point of telling them? Even stories that seek to provide an ‘escape’ from reality, do so by first acknowledging that reality, before proceeding to depart from it. By default therefore, reflecting it, although obtusely.

‘Ajji’ is a response to what has always been happening in our country. Gender bigotry has always been one of India’s biggest tragedies. In the last few years it’s just happened to get reported more, because of the freedom of reportage the online space allows. So we’ve been hearing more about episodes of sexual violence recently. This doesn’t mean it’s been happening more in recent times. It has always been this bad, perhaps worse.

We had had this story idea for a long time. But films need that dreaded M word to find fruition – Money. And money comes to films that carry the promise of the other dreaded M word – Market. It was perhaps because ‘rapes’ were ‘in the news’ that our story suddenly found producers willing to put money in it. I know it sounds brutal, but I’m trying to say it like it is, without beating around the proverbial bush. ‘Saying it like it is’ is the spirit with which this film was made.

Most of it is shot at night. Being a low-budget film has its own set of logistical issues, but shooting at night in remote spaces is an extra layer of problems. Is that why most scenes tend to play longer at a single location, riffing more on atmosphere and mood rather than flow?

DM: The choice of night was simply to make Ajji’s journey more difficult. How does an arthritic, domesticated, introverted grandmother navigate the unpredictable dangers of the urban underbelly at night? She would be a most obtrusive sight. And she doesn’t have any of the tools one needs to survive that world. It was insanely difficult, given we had a frighteningly sparse budget. Most of the exterior scenes are shot ONLY by tubelights.

I am not a big fan of films in which locations change every minute or so (I’m not talking about road-trip films here, those need that). The constant ‘displacement’ often doesn’t allow the mood and tone to seep from the character into the action. In films with shorter scenes where the action often shifts locations, the action dictates the tone. And ‘mood’ is often compromised.

Some of my favourite filmmakers – Kieslowski, Aronofsky, Hitchcock, Kubrick, even Umesh Kulkarni – can make an entire film riff compellingly off a single location. It boils down then to the characters – and what one can draw from them to build the atmosphere and narrative drama with. Tarantino does that spectacularly, in long drawn-out dialogue scenes in a single room sometimes.

Although I admit did use that approach also to achieve a film as ambitious as this one in the shockingly low budget we had.

Tell us a little about the trials of making such a film. Physically, yes, but even mentally, given that it is such a difficult subject. Does it take a toll on the people involved, waking up every day and creating a world that is virtually unbearable to occupy?

DM: At the rapist’s lair – a construction site – I needed to create an alternation of light and shadow – to make Ajji’s navigation of the place difficult, dangerous, eerie even. I wanted to create alternating pockets of light and shadow, like in a jungle, where the moonlight filtering through the branches of trees allows one to see some bits of the jungle floor, but the bits the light doesn’t reach are pitch-dark, and that’s where the beasts of prey lurk.

To create that we would’ve needed many lights, rostrums, generators, the works. There was money for none of that. There was only enough money for about half a dozen tubelights.

What to do?

It struck me that I was trying to create this alternation of light and shadow in the dimension of SPACE. What if I utilized the other dimension – that of TIME! What we did then was to simply FLICKER one of those half a dozen tubelights! Constantly. And I got what I needed…only, the light and shadow alternated over Time now, and not Space.

Challenges like these were merely logistical ones though.

This particular film had more dangerous repercussions on the minds and bodies of those involved. Some actors suffered behavioural issues during the making of the film. Some of my team, too. The pressure of achieving the near-impossible aside, the narrative material we were working with was a tight slap in the face of any and all ‘life-affirmation’. Every day this story reminded us that we are arguably the most vile, the most self-serving, most ruthless, unkindest, most conniving, greedy species on this earth. Its not easy to go through your days with that knowledge sitting tight on the tip of your nose.

I’m having an honest moment here, so I’ll share something which has been very private all this time. In the few months we spent researching this film, we made contact with some young victims of rape, their parents, the lawyers and NGOs representing their cases. Each story was more heartbreaking than the last. I reached a point in the middle of last year when every woman I spoke to had a personal story of abuse to share. I came to realize that we men spare no woman the ignominy of transgression. It might be at the hands of an uncle, a grandfather, a cousin brother, a neighbourhood shopkeeper, a teacher, a stranger, a thug or a father. But no woman is exempt. I started to hate myself for being a man. I didn’t realize the effect that was going to have on me. We finished the script by early August. I was to shoot in November.

In September I pissed blood.

I was in unbelievable pain for weeks. Amongst a host of tests, a doctor prescribed I get my prostate tested. The counts were so haywire that the urologist at Hinduja declared I might have Prostate cancer. Procured over the last few months perhaps. I was asked to get a host of tests done, urgently. I was to shoot in 5 weeks. I begged for medication that would see me through my shoot. I’d waited too long to make a film. At the risk of sounding dramatic, If I was to die, I chose to die shooting Ajji.

I shot the film…on 2000 mg antibiotics a day, still unsure of what I was going to do about my prostate cancer(?) once I finished the film (IF I finished the film). A dear friend who believes in holistic healing sent me something wonderful. She connected my prostate problem with me hating on my masculinity. That’s when it all fell into place. I was so angry at Men, that I had imploded. I had directed the anger of Ajji deep within myself. And it went and nearly destroyed the seat of my own male-ness – my prostate.

Over the post-production of Ajji I worked on healing myself. I can talk about this now because miraculously my prostate counts have plummeted to normal levels. It is no longer a cancer, probably never was. It was a horrific prostatitis – that dissipated when my anger found channeling outwards through this film perhaps.

I don’t know what this film will do for those that watch it. But I know that it almost killed me. And since it didn’t, it has made me stronger. But I’m still very ashamed of being a man in a world where men are slaves to their penises.

Did you worry about the Censors while writing/conceptualising? Was there any point during production when you had your doubts?

DM: Yoodlee Films originally planned to release their films digitally only. That would not put this film at the mercy of the certification board (not ‘censor’ mind you). They gave me the freedom to push this film off the edge. Also, since the material I was working with had disturbed me at such a deep level, it made no sense to me to not disturb the viewer to that same extent (if possible) too. If I didn’t, it would be a disservice to the very intent of this film.

It also helped that – like I said earlier – I was trying to subvert the archetype of rape and revenge. Often such films make either the rape or the revenge (or both) ‘sexy’. And I refused to do that. I wanted the horror – of the act, and the (lifelong?) aftermath – to transfer to the viewer. For that, I would have to toss all doubts into the trashcan, and leap off the edge.

Are you worried about people terming this as “exploitative” or tasteless? Most audiences here — unlike maybe the South-East Asian countries — aren’t quite conditioned to such uncompromising images.

DM: “Uncompromising images” is an eloquent choice of words. Like I said I needed to transfer the horror to the viewer. I admit that can be unpalatable to most viewers, since we’re not conditioned to consume such through our Cinema. I’m prepared for the film being called all sorts of things. One gets ‘worried’ when one doesn’t want to deal with something. I’m eager for people to question me about my choices in this film. I’m also hopeful of frank, open and unhindered debate. The only way forward from injustice is Dialogue. If this film – by being called all sorts of things – could open up conduits for dialogue and debate it’ll all have been worth it.

Tell us about the casting process. How did Sushma Deshpande react to the script, and the possibility of such necessary graphic enactments? What was your brief to Abhishek Bannerjee?

DM: Sushama is the guardian spirit of ‘Ajji’. I did not know that a woman existed in the universe who had been born to play Ajji, and had been lying in wait all this time for their paths to cross. I feel like merely a channel that was chosen to make Ajji and Sushama coincide. I know I sound like a silly fool saying all this, but this comes from a place of deep love for the immense artist that Sushama is. This is her first ever lead role in a film. It’s practically her first bonafide feature film. And we didn’t even audition her.

My casting directors – Abhishek Banerjee and Anmol Ahuja – had gone through many options. Several wonderful actresses turned down the part because they disagreed with the morality of the film. Suruchi, a friend of my co-writer Mirat, recommended we check out Sushama. Sushama was reluctant to meet even. It’s not something she does – meet people for film. She’s primarily a theatre artist. But she came for a lark. And when we met, something shifted. In me, and in her.

After that one meeting, she questioned nothing. She surrendered herself to the service of the film. We made her chop mutton, halaal a cock on camera, carve a goat. And she never once showed even a flicker of reluctance. Given that she’s a vegetarian!

She had worked extensively with feminist themes all her life. She has written, directed and performed the one-woman play ‘Savitri’ for over 35 years now. She believed in the graphic-ness of this film as much as I did, if not more. She doesn’t mince her words. And that spirit found resonance perhaps in the spirit of this film. Amongst many other subtexts, this film is also a reimagining of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ – that treatise on child abuse in the garb of a bedtime story.

So I asked Abhishek Banerjee to play Dhavle (the rapist) as a lascivious, fanged, cocky, prowling WOLF…always hungry for flesh. To a rapist a woman is not a woman, she gets abstracted into a ‘body’…into ‘flesh’…with no identity or consciousness…she’s simply a piece of meat to be consumed. I needed Dhavle to epitomize that – to distil a rapist down to the most basic idea that constitutes him = a consumer of meat…the woman being the meat. Dhavle the wolf is king of his little concrete-jungle lair, lying in wait every night for his lackey Umya to bring him his meat for the night.

You’ve come from an assisting and short-film background. The short-film landscape has changed a lot in the last few years (digital boom, viral etc). You’ve been recognised for them. Has that helped you a lot — both craft-wise and exposure-wise — to take the plunge with feature-length ambitions?

DM: Actually not. Mine is a strangely reverse journey. I was in the feature film space for almost a decade. I had over a dozen films get shelved in different stages of production, including a big budget animation film I was writing and directing for three years for the YRF-Disney combine which also churned out the abysmal ‘Roadside Romeo’ – the disastrous film that ensured that my under-production film would be shut down in the last stages of animation.

The first film I saw to completion though – Oonga – too didn’t work out as I intended. The producer and I – after a point – were trying to make two different films. My desperation to make the film (since I’d seen so many films bite the dust before this) made me weak. And I couldn’t fight to protect the film. It wasn’t shot the way I intended, and I wasn’t allowed to edit it my way either. The final film is not really my film. For a couple of years after that experience I had severe self-doubt. I wondered if perhaps I wasn’t a filmmaker at all. I needed to prove to myself – and to the world – that perhaps I did have it in me to make films my way. Short films allowed me that.

Today I can look back with some clarity on my Oonga experience and recognize it for the mistake it was. If I had not been made helpless by my own desperation I feel sure today that I could have made Oonga a much much better film than it turned out to be. My short films have done more for my viewers and prospective producers than they have for me. Prospective producers probably give me the little money they do now because they believe there is a small ‘audience’ for my films?

What is the most important thing that you have learned from AJJI? And what next?

DM: Learning is something one does in retrospect. If the film fails spectacularly, there might be no learning perhaps. I cannot tell right now. If certain things end up seeming like ‘mistakes’ I might still proceed to repeat those mistakes, because what seems like a mistake on one film might actually serve the next one well — because each film is a wholly different organic beast.

I’m two weeks from the main shoot schedule of ‘Bhonsle,’ the feature Manoj Bajpai and I have been trying to make together for almost 4 years now. This is the feature that spawned Taandav early last year. We’re still struggling to keep the finance in place. But with over a decade of watching my films crash and burn over and over, in different ways, for different reasons, there’s one thing I’ve learnt well – it’s to take the film fight strictly: One.Day.At.A.Time.

AJJI screenings at the Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival, 2017:

October 13, Friday, PVR ICON 1 (8.25 PM)

October 14, Saturday, PVR KURLA 8 (7.15 PM)

October 16, Monday, PVR ICON 4 (5.45 PM) *Q&A

October 17, Tuesday, PVR ECX 5 (8.40 PM) *Q&A

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.