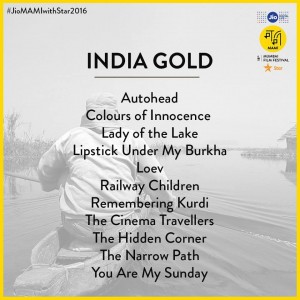

After first making waves at the 19th Black Nights Film Festival in Tallin (Estonia) last year, and proceeding to many prestigious LGBT festivals across the globe, Sudhanshu Saria’s LOEV — the hypnotic story of a weekend exploring the complex equation between three Indian friends — is finally coming home. It will have its Indian premiere at the 18th edition of the Mumbai Film Festival, Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival With Star 2016, as part of the much-anticipated INDIA GOLD section. The film stars three young actors: Shiv Pandit (Shaitaan, Boss), Dhruv Ganesh (Teen Patti, Table No. 21) and Siddharth Menon (Peddlers, Rajwade and Sons).

Insisting that there’s more to the world than “cliched stories of gay men being persecuted and ostrasized,” Sudhanshu refers to LOEV as a ‘post-gay’ film, where characters aren’t defined by their sexuality. A difficult thought to digest in this country, he admits, but his film — unlike many others in the genre — does not really focus on homosexuality as the primary issue. It remains about human relationships and its various hues.

The debutant director spoke to us a while back soon after the World Premiere, where he elaborates further about his experience making this film, his ambitions and an unerring commitment to simplicity.

Tell us a bit about your journey so far.

A. I was born in Darjeeling to a Marwari family, as far away from the world of films as you can imagine. I grew up on a steady diet of Bollywood and Filmfare/MOVIE magazines, but actually working in the industry just never occurred to me. I didn’t even consider it as a means of livelihood. It wasn’t until I was in college in upstate New York (Ithaca) and I saw some film students spooling film into their Bolex that I understood I could actually pursue film professionally. Once I figured that out, like many others, it was just about applying all my stubborn, obstinate energy towards it and et-voila! Here I am!

How and why did LOEV happen?

A. All good films come from something personal, something real. I was dealing with personal heartache too, and decided to deal with it through my writing. The script just poured out of me. Setting it in this milieu, and picking male protagonists, gave it an exciting energy. Moreover, and this point becomes clearer once you’ve seen the film, I wanted the characters to be completely responsible for their actions; I didn’t want audiences to allocate any blame or excuse any behaviour because of their gender. I liked how making them all of the same gender made them each completely responsible for their actions.

It’s unfortunate that any film that deals with themes of homosexuality is called ‘brave’ here. Much like honesty is treated as a heroic deed here. Did you set out to be brave, or just to make a multi-textured road movie?

A. Maybe the actors were being brave by risking a certain typecasting, and I know as producers we were being brave by putting money into something that doesn’t really have an obvious exit strategy. But as a director, I am so so grateful this story fell into my lap. It’s been a joy to tell, so simple and yet powerful. When I look around me, I don’t see any simple definitions of love, no set patterns in how relationships flow and I just wanted to capture that. Something nuanced, simple and honest. That’s all.

Can’t have been easy to shoot in this country. However, the film looks planned, and not guerrilla or such. Any major problems during production?

A. I was pretty clear from the outset that the only way to make this film would be the tough way. Given the subject matter, I couldn’t afford to spend lavish amounts of money. We had to plan well, be extremely frugal, count every penny and make sure it all ended up on the screen. The film belongs as much to my crew — some of them invested their salaries back into the production to help this thing get made. It was obvious to all of us that if we wanted this story to be told, we would have to help it get to the finish line. The ‘permits’ bits were tough. We didn’t really know how authorities would behave once they found out what we were up to, so we always had a more diluted script with us. Some of the crew only found out about the sexual orientation of these characters as they saw the story unfold during the production.

Tell us about how you got your actors in place. The inherent awkwardness sometimes seems to work with such themes…because nobody is quite sure how open to be about their sexuality in India anymore. Even acting flaws can sometimes be passed off as character deficiencies.

A. Since I’m quite new to Mumbai, it’s not like I knew too many people. Shiv Pandit was on my radar because we had attended the same boarding school. I thought he had an interesting look, like a quiet anger inside him. But I also was told by a lot of casting directors and friends that he would never agree to do something like this. We were keeping the script quite close to our vests, so I didn’t want to waste a narration on an actor who might say no and potentially gossip about what we were doing. But Shiv surprised me. He was persistent about hearing the film and just delivered the goods during our meetings.

For the other two actors, we must have met with every single young male actor in Mumbai. I was looking for a fierce naturalism; they had to hold the camera for ten minutes without blinking an eyelid and it was quite aggravating. I didn’t want that demonstrative, high-pitch acting that has come to be associated with our cinema here. One of our producers had put Siddharth Menon on the short-list. When he walked in, I immediately recognized him from his miraculous work in Vasan Bala’s (unreleased) Peddlers. I had seen it some years back in LA and it had really left a mark. So the moment he walked in, I sort of knew he was in. We found Dhruv Ganesh through auditions. Nicest guy, so sincere and when he started the scene, it was just so obvious that he was the very best Mumbai had to offer. His choices were so original. I’m just thrilled I got to collaborate with these guys — they truly are the soul of the film.

There’s always this problem of making Indian films with English-speaking Indian actors. Doesn’t seem natural. Despite your film’s distinctly urban roots and setup, were you a bit apprehensive about this?

A. Hmm. It’s not really something I thought about. I’ve only been in Mumbai two years and the language in the film is really the language I hear around me. It reflects how my local friends and relatives here talk. Despite having spent all those years outside Mumbai, I can still speak and write better Hindi than most of them. So it was just about paying attention to detail and making sure the words flowed and felt natural to them. Shiv’s character lives in Manhattan so that was a bit more work for Shiv. We spent a fair bit of time separating the nuances of the English spoken there versus how we use the language here in Mumbai.

Good films make viewers forget that they’re watching two men or two women fall in love. However, here, that is exactly what such films get noticed for. The whole equation changes. What do you expect when the film opens in India?

A. This country is crazy about love stories and I imagine they are quite tired of the same old stuff. So I expect they’re going to really go for this film. It’s different, it’s original, it’s heartfelt…it just reflects the world around them. They’re tired of the same old garbage. Our audiences are smart and when we respect them, they always respond.

Do you think the criminalisation of homosexuality in India will affect the way they view the film here? It won’t be just another love story for many.

A. Maybe it will make those outside the LGBT community empathise more with these characters? I hope it helps viewers recognise how brutal, confusing, merciless, unrelenting love is on its own terms, even without society’s interference and all these rules and perceptions. I hope it makes them feel empathy and love towards anyone in love. We don’t need to make things any more difficult for them.

Any particular filmmaking influences or inspirations over the years?

A. Dardenne Brothers. Eric Rohmer. Hrishikesh Mukherjee. I’ve truly come to respect, love and worship simplicity. It’s the hallmark of masters. My needs and my own ego are irrelevant — I simply want to tell the story and get the hell out of there.

What have the reactions been like so far? How receptive have people been?

A. It’s been overwhelming. They are seeing every detail, all the design present in this very simple movie. While we were editing, we hosted a bunch of small screenings to gauge how the characters were being perceived, and the reactions were always amazing. We’ve had groups arguing over who was right and who was wrong, whose fault it was and so on for hours after it ended. When we started, I thought I was making an obtuse, art-house movie for European audiences but it’s turned out to be more desi than I thought. Given the characters are men, I was warned that women might not be into the film, but they’ve been the most passionate about LOEV so far.

What kind of storyteller are you?

A. Honesty. Transparency. Truth. The subjects can change but I would always like to approach every film with these core values, and just really try to get to the core of what the film or the character is about. It’s a lot of work. It takes a lot of resources and uses up a lot of people’s time. I want to make sure the movies I make do more than just entertain. And I want to try and pick subjects that have a lot of me in them; films that wouldn’t be as good if I wasn’t involved. It’s too much work to just be a cog in the machine.

The title is striking. Significance?

A. This is a mature, complicated, nuanced story about a different kind of love. It covers all the loves outside that Yash Chopra love; the sort of love I find quite common in the people around me. Confused love, misguided love, misplaced love, love motivated by other factors — stuff that looks (like) love but isn’t. So the title sort of acknowledges that.

What was the reaction at the Tallinn World Premiere?

A. It’s my first time, so it’s hard to contextualise. Perhaps when it opens here (India), and people like you react to it, I’d get a better idea. Estonians are known to be quite reserved and stoic. We had to cancel the Q-and-A afterwards because of how emotional everyone got. The audience stood up for a minute in silence for these characters. Lots of hugging and tears after. Hard to understand, even for me, what this film is. It’s just a personal photograph. But I have no way of knowing, yet, why/how/if it will resonate with anyone else. In any case, I’m grateful and surprised from the reactions so far.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.