Last year, Shyam Benegal and a few industry veterans had a panel discussion about the meaning and language of Indian Independent cinema. None of them, including the audience, came back any wiser, writes Tanul Thakur.

Everybody loves a good underdog story. The vicarious joys of watching the Davids take over the Goliaths are undeniable because, let’s face it, a majority of us have convinced ourselves that we are indeed the Davids — powerless, ignored and tottering on the edges.

When it comes to films, this perception is not markedly different.

For the last 10 years or so, terms such as “independent cinema” or “New Bollywood” have been frequently and casually tossed around to describe films that are even slightly different from the mainstream.

In the recent years, buoyed by some impressive successes, the commentary on Indian independent cinema has also undergone a marked shift — from genuine excitement to naive banality, where the majority are running around in circles, repeating the same things, without really understanding the origin and import of this “movement”. Let’s get the basics out of the way first: what do we really mean when we say “independent” cinema? Does independent mean producing films without the help of established production houses? Or does it refer to films made with different aesthetics — employing cinematic grammar, storylines that are beyond the realms of the mainstream cinema?

Earlier this week, I attended one of the panel discussions at the Jagran Film Festival in New Delhi, whose topic had puerility and naivety written all over it.

The talk was titled: “Is independent cinema taking over Bollywood?” In my opinion, it’s precisely these kinds of overly simplified declarations that taint the real meaning of a change.

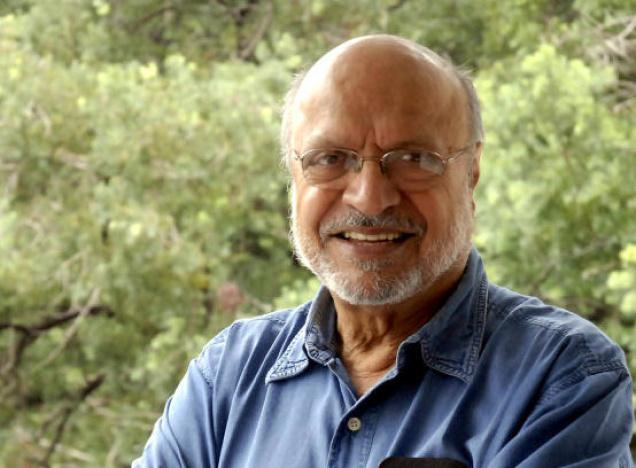

Held at Siri Fort Auditorium, the panel was moderated by Atul Tiwari (screenplay and dialogue writer of films such as Droh Kaal, Mission Kashmir, Vishwaroopam), and its participants included Shyam Benegal, Pavan Malhotra and T.P. Agarwal. As the discussion began, Tiwari clarified at the outset: “I am only a moderator; I haven’t decided the topic. It’s been decided by the Jagran group.” This clarification was necessary because if a bunch of industry veterans are really contemplating — without any tinge of irony — whether the independent cinema is “taking over” Bollywood, then you can do nothing, but shake your head slowly in disbelief.

“I am confused by the term ‘independent cinema’,” said Shyam Benegal, as the discussion began. “Because the studio collapsed by the late ’50s; films or filmmakers have been independent since then. However, a distinction must be made about the different kinds of films — certain kinds of films that followed the format of popular entertainment were of one kind, and those who broke away from that, those who used different narrative styles started to be clubbed under ‘parallel cinema’. So you have to make those little distinctions; you can’t automatically assume it’s such a simple thing. I want to make it very clear that when we talk about independent cinema, we are talking about a person who’s primarily looking at films as an aesthetic product, and secondarily as something that would make money and return investors their money.”

Pavan Malhotra, who began his career with offbeat films in the ’80s, and who has successfully transitioned to mainstream films since, said, “Independent cinema is not at all taking over mainstream films. Even today, ‘proposal making’ is in vogue — ‘take a star, we will talk about the script later; we will have five action sequences, five songs’. It’s prevalent even today. But then those filmmakers must be asked: why is your ratio of success still the same? If one Rowdy Rathore is successful, then there are 10 more films on similar lines, out of which eight flop.”

The topic veered to the industry behemoths — the towering Goliaths — who dictate terms to producers and filmmakers, almost forbidding an alternate cinema to flourish. “I went to Akshay Kumar a few years back. He told me, ‘You invest money. I will give you the story, the director, other actors, and we will make a film.’ In that case, what film will I make?” said T.P. Agarwal, a Bollywood producer who has backed films such as Policegiri, Red Alert: The War Within. “For instance, Hansal Mehta made a film like Shahid. The lead of the film (Rajkummar Rao) was signed on for just Rs 10 lakh. Now, he’s asking for Rs 2 crore. Now, you tell me, how can you make a film like Shahid in Rs 70-80 lakh?” Pavan Malhotra intervenes a little later: “Like how Agarwal saab was saying, ‘that actor is charging Rs 2 crore.’ Well, that actor is asking for Rs 2 crore because you are ready to give someone else Rs 50 crore.” Agarwal replies, “But it’s not like the bigger stars can guarantee hits. I am not objecting to that Rs 2 crore. But those actors should first deliver at least give six-seven quality films.” “So you are saying, after acting in one film, I should look for something else?” The audience chuckles. Benegal comes back to this later: “There must be a certain basis on which actors or technicians are paid. Currently, the system is meaningless; it shouldn’t be like a lottery.”

Besides the lack of funds, a major conflict for independent filmmakers is content — the kind of films they want to make, and the kind of films the audience wants to see. The National Film Development Corporation of India (NFDC) was founded in 1975 to address a similar concern: “to create domestic and global appreciation and celebration of independent Indian cinema”. Through the years, the NFDC has helped produce a lot of offbeat films. It has been a noteworthy chapter in Indian cinema because it at least signalled intent of changing times.

However, Benegal feels the NFDC could have done a lot better: “We had this problem with NFDC-financed films at one time; you had filmmakers who came and made films, who were struck with this sense of them being geniuses of one kind or the other, and then they made the kind of films no one wanted to see, except themselves. Cinema is ‘public art’; it becomes fulfilled only with an audience. Films have to be entertaining.”

It’s the kind of statement you expect from inept, mainstream Bollywood filmmakers. So coming from someone like Benegal, this disconcerts you for a moment. Because the real meanings of “entertaining” and “boring” films are at best nebulous, and if some filmmakers won’t make personal films that play around with both content and form, then the film industry runs the risk of being stagnant, or to use a much abused word — “boring”.

However, Benegal does clarify himself a little afterwards, when he says films — irrespective of what kind — have to primarily “communicate” to the audience. That’s a little better argument than making sweeping generalisations about “entertaining or boring” films.

Malhotra, who was also a production assistant at the NFDC at one point, has some additional gripes with the organisation: “Of course, it’s true that the NFDC has given actors and filmmakers to the industry, but at the same time they did a horrible job with the distribution. I acted in a film called Bagh Bahadur (1990), which won a National Award. Till date, its DVD has not been sold. Don’t tell me there were no buyers. I also remember there being no hoardings for Bagh Bahadur when the film hit the theatres. So there was huge mismanagement. Now Anurag Kashyap can go abroad to sell his films, but the NFDC wasn’t successful in selling its films.” Benegal agrees: “When it comes to the marketing of films, the NFDC was totally incapable and found wanting from the very beginning.”

The questions about independent cinema are way too many to be neatly addressed by a 60-minute conversation.

And I went into this panel discussion with a healthy dose of scepticism, but by the time it got over, I wasn’t disappointed. Mostly because the panellists acknowledged that there are no definite, immediate solutions to the question posed at them, and perhaps that’s how these conversations are best approached.

A thing in transition is often beautiful, mostly because it’s unpredictable, even unsure of itself; its inchoate identity keeps telling you to not simplify, to understand the intricacies. It’s in situations like these where quiet observations are as powerful — sometimes, even more — as assertive, declarative opinions.

Or as Benegal says in the course of the discussion: “The final word on this has not been spoken yet.”

(This piece was originally published in The Sunday Guardian)

Tanul Thakur (@Plebian42) is an award-winning film critic and journalist. To read more, visit his blog at https://tanulthakur.wordpress.com

Tanul Thakur (@Plebian42) is an award-winning film critic and journalist. To read more, visit his blog at https://tanulthakur.wordpress.com

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.