During my internship at Leo Burnett in Bangalore (India), I was voraciously lapping up experimental and alternative short film content. I was drowned in National Film Board of Canada films, Films Division (India) and watching rare masterpieces such as A Szel by Varga Csaba, Repete by Michaela Pavlátová, Zbigniew Rybcznski’s Tango and other classics by Norman McLaren and Ryan Larkin. I was on a quest to understand how different forms, mediums and styles can be used to tell stories more effectively and convey deeper emotion in a scene, as opposed to conventional narratives.

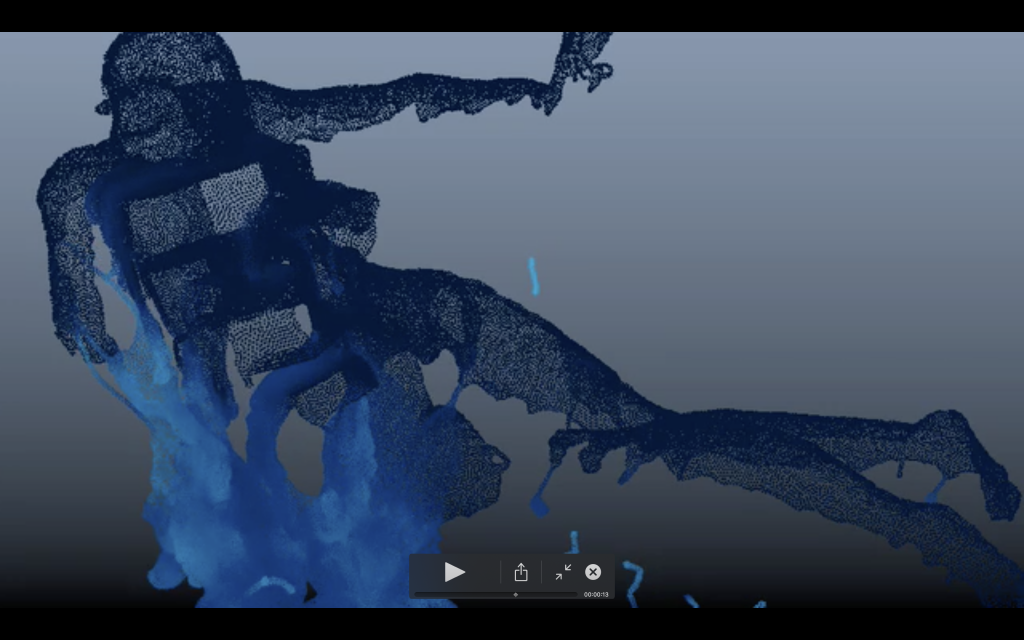

I recall writing articles for online publications to deconstruct imaginative storytelling, and experiment with different techniques to create greater visceral impact. My long-drawn passion towards animation, too, made me watch a tonne of sand animation, puppet and shadow animation, pixelation, mixed-media films, bead animation and classical hand-drawn work. However, when I stumbled upon Choros by Michael Langan and Terah Mayer, it instantly reminded me of the Navrasas, or the journey of the nine emotions, expressed through mesmerising strobing. The only earlier film I recall which had effectively used strobing was McLaren’s Pas de Deux. The film had blown my mind. In any form of storytelling, be it cinema, singing or the performing arts, what connects to the soul the most is the way the story is expressed, or rather what the Natya Shastra calls the nine moods, sentiments and phases that the soul goes through on a daily basis. Choros, uses image multiplication, dance and music to convey the dancer’s (Mayer) experience of discovery, euphoria, and rebirth through the surreal imagery of a single dancer and a chorus of women which emerge from her.

At 17, I had directed a challenging, experimental pixelation film called Religion for Dummies. I wanted to be more ambitious in my next short film and pay a tribute to the great masters, McLaren and Langan & Mayer. It was during this time that I happened to have read about the tempestuous and surreal relationship of Gala and Salvador Dali, the Spanish surreal painter. It is said that without Gala, who eventually became his manager, Dali wouldn’t have been an icon of the modern art movement that he became. In his Secret Life, Dali wrote: “She was destined to be my Gradiva, the one who moves forward, my victory, my wife.” Gradiva came from a novel in which she was a character who brought psychological healing to the protagonist. Gala also became a frequent model in Dali’s work and in the 1930s, Dali even started to sign his paintings with his and her name. He proclaimed, “It is mostly with your blood, Gala, that I paint my pictures.” It was this that inspired me to embark on Dali, a musical short film that I directed in 2018, which was to capture the Navrasas in Dali’s life, right through his poetic relationship with Gala. Perhaps I had bitten more than I could chew.

As if attempting something like Choros was not challenging enough, I decided to complicate the technical aspects of making the film further. On instagram, a few months later, after having written the first draft of the film, I stumbled upon a video which displayed some anamorphic sculptures. These sculptures were basically distorted projections which required the viewer to occupy a specific vantage point to view a recognisable image. I decided to re-write the script and include Dali’s original artworks in the film as anamorphic sculptures. What this meant was that the artworks would be broken into several separate planes that were at certain distances from each other in a three-dimensional space. Only when the camera tracked to a specific point, would the whole artwork be visible and take form. The idea of doing this fascinated me, but I didn’t realise how technically complex it was to execute. I dived in nonetheless, knowing little or nothing about visual effects. What excited me about this venture was that I knew this film would be the first and only Indian short film that would have used image multiplication and anamorphic sculptures.

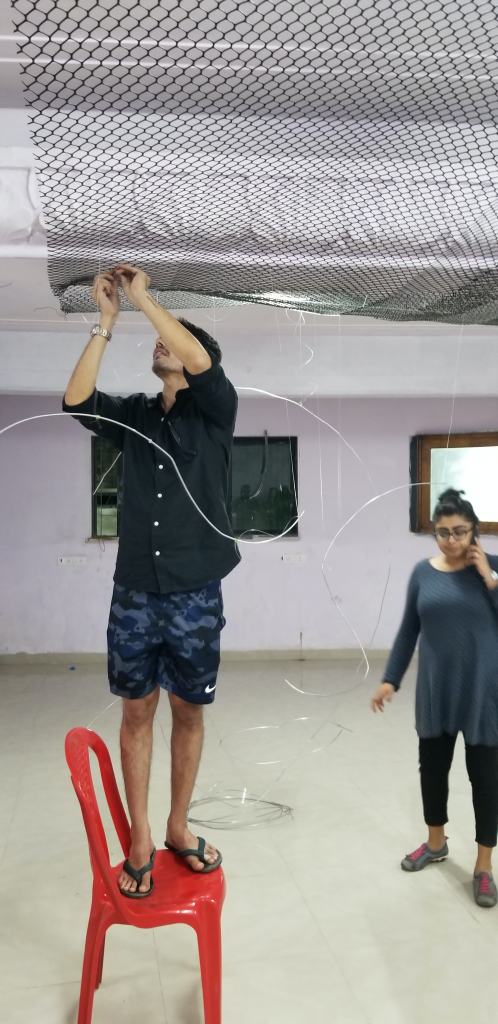

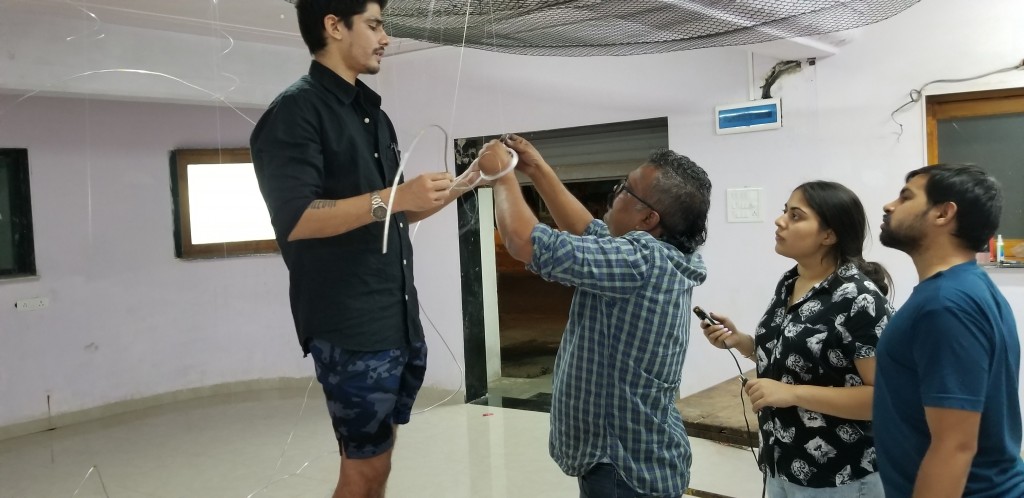

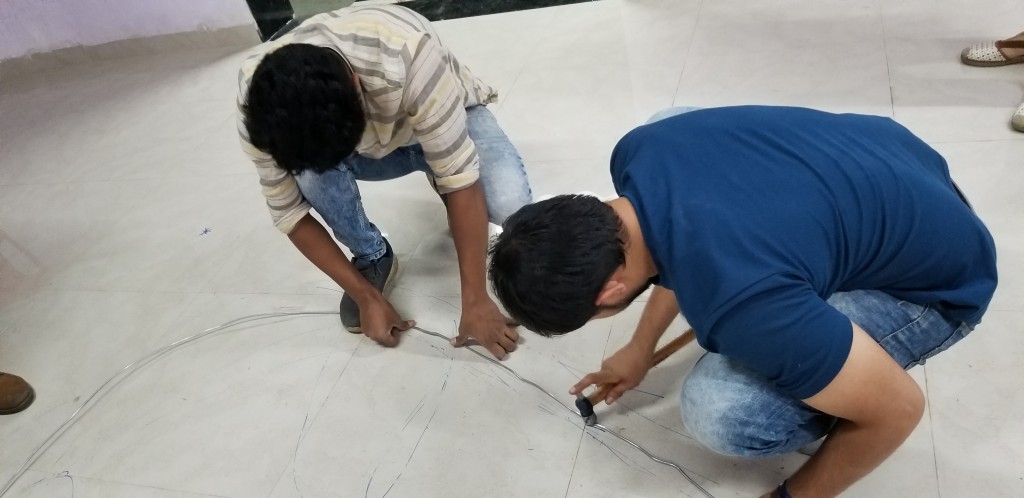

To achieve these two experiments, we did several test shoots initially and a month or more of prepping in the art department. As researched showed us, first to create each anamorphic sculpture on screen required us to split the outline of the artwork up digitally into five parts. Each part of the outline would be made into scaled-up wire frames, which were hung up and placed a certain distances from each other which were measured.

We used conventional methods of eyeballing to ensure that from the final vantage point, the entire outline of the artwork was visible. Now, the next step was to shoot the dancers against chroma, following the movement that the wire frames set for them as reference in their choreography. The camera would start moving from the side and track till the final vantage point in the shoot. The wire frames were then keyed out on After Effects and replaced with brush strokes, before the colours bled in to the final image and the artwork formed on screen. We used several 3D mapping and modelling softwares to calculate the distance at which these wire frames were to be placed from each other. Also since these wire frames were large and fragile, they had to be lugged to the studio and hung from 17ft height using transparent fishnets each time.

For the strobing/image multiplications too, we initially began with some test shoots to experiment on how it was to be done. We would shoot each shot five times or more, to get more echoes in their movements. Soon enough, we realised it could be done digitally as well. For the story to organically develop through dance, we had a month of intense rehearsals with the two actors to ensure that the story was coming through in their movements. The music too had to have multiple mood changeovers, and the initial score was composed and finalised before the film was shot.

The entire 9-minute nugget, shot entirely against chroma, dragged on for a year and a half with a crew of 170 people working on pre-production, shoot and post. At times, it just seemed impossible and a foolhardy attempt to complete the film. Weighed in by the enormity of the task, I almost abandoned the project several times along the way. The rotoscopy drudgery took the wind out of the sails as we had several issues keying out the chroma in many shots, especially around the hair and the feet of the two actors. It was an excruciatingly long and frustrating process, especially since at the time I was still in college, and remotely trying to direct the post-production and complete the entire film. The final piece of music was recomposed by Emiliano Mazzenga at the University of Southern California (USC).

But once the film was done, it was a fulfilling experience. Well appreciated and awarded, Dali is a film that I am proud of.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.