By Priya Bhattacharji

The question you get to hear these days that both annoys and amuses: “What’s wrong with this country?”

Whenever the nation’s horrors creep into media feeds, the woke folk on social media are ever-ready to prod and preach. Arguably, the most flammable topic of debate for urban Indians is “Real India”. Social networks fiercely rage with a multitude of conflicting discourses and histories about “Real India”. Living in tinted glass buildings, sitting behind the bunkers of our screen in air-purified spaces, Urban India is beset to operate at low-visibility. It’s rather easy to be in denial about social deformities that have long existed in the hidden and camouflaged in certain pockets of the country.

What’s refreshing to see, though, is filmmakers of privilege mount off their high horses and dare to befriend this ‘Real India’. The recent past has witnessed a wide range of shorts, films, documentaries making a notable effort to explore various socio-cultural debilitations of India.

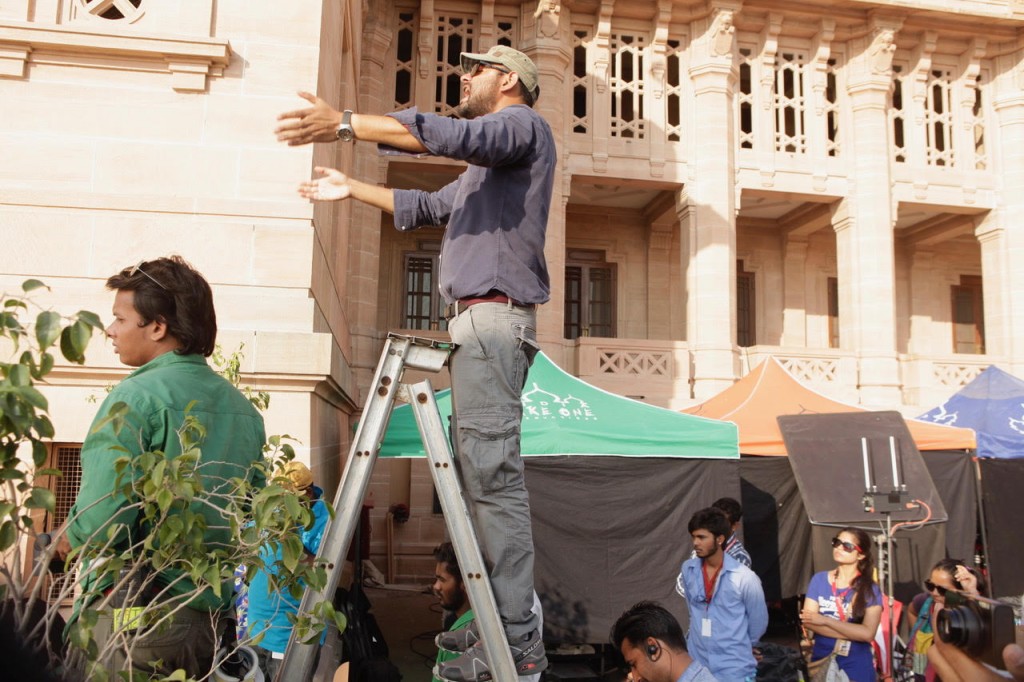

Delhi-based Udayan Baijal is one such person. He has a uniquely rich, layered career in film. Co-founder of Jamun, one of Delhi’s most avant-garde production houses, he has also worked as 1st assistant director to an enviable list of international heavyweights that include The Life of Pi, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, Zero Dark Thirty, The Reluctant Fundamentalist and The Dark Knight Rises.

Armed with a rare brand of well-checked privilege, Udayan has traveled the length and breadth of India to work for the finest names in the Indian and international film business. Without much name dropping, he takes us through his fascinating journey, offering valuable tips on how to carve a career in independent film and the ‘other’ India he interacts with.

What does it mean to an assistant director in India to some of the biggest international names?

UB: India is a harsh landing ground for most foreign crews. Some give in to to the chaos, some try and fight it. I suppose what works is to give up a way of working you know very well in your own countries and adapt to a method that works efficiently in India. As an assistant director, I schedule the film and run the shooting floor for the director. I’m often the person who helps coordinate with various departments to ensure that the director’s creative vision is never compromised.

You have to make sure your director gets everything they need to make the day – get all the scenes planned in the best possible way. The system I have worked in and learn from is very detail oriented. In most cases pre-production and production are planned to a calendar with deadlines that have to be met. It is not unusual to know 2 months prior to a shooting day what scene will be shot at sunset and what one will need to make that scene magical – actors, extras, special equipment, art, wardrobe, the works.

Most international directors are unbelievably organized (some are not, but that is usually an exception); they know their material inside out, and you have to step up your game to make sure you don’t let them or the film down. On all the international feature films I have done, one has to follow a strict shooting schedule, and it’s my responsibility, with a lot of support from several departments.

Having worked closely with the likes of Kathryn Bigleow, John Madden and many others, you realise, for the most part that there is a very high level of professionalism in the British and American film environment. Most people stick to a specialised job for a long career and this makes them exceptionally good at what they do.

Sure, there are times when these systems and structures can’t survive the Indian-ness of India. At times, things work in a way quite the opposite of what is planned. To get things done here, you have to plan like a military machine, but be prepared to work like a circus.

So what is it exactly that you do as an assistant director?

I have been a 1st AD for over a decade, but find it very hard to describe what I do! Your job is basically to nudge/push/cajole the crew to get the best out of them for the film. The job varies a lot from day to day and project to project. Sometimes you have to push your own department, sometimes other departments, and while doing this, one still has to create a positive and relaxed atmosphere on set for the scenes to work. And for that, you have to handle every head of a department differently. There is a hidden architecture to the making of great cinema that needs a fair bit of planning – once planned, you can let improvisation and unstructured magic happen. This always fascinates me.

On some days the job will demand being very particular (almost obsessive) about, let’s say, stunt rehearsals, on other days it will be to keep things quiet and very low-key for actors to perform sensitive scenes. The role requires you to alternate between being a monster and a therapist on set.

You’ve also been an assistant editor for Slumdog Millionaire for which you got a mention at the Oscars? That must have been some experience.

In 2007, I was fortunate to win the INLAKS Scholarship from India. I received a ‘take off grant’ that supported me financially for work attachments in New York and London. In New York, I had an amazing stint at Emerging Pictures. It was a great space to work out of. And I learned some very valuable lessons about the importance of distribution and marketing. The methods of distribution have changed since my time there, but the lessons I learnt about how to think about distribution were invaluable.

During my stint there I realised that an amazing film with no plan on how to find its audience is going to find it hard to get people to watch it. This is still true and I don’t think anyone has all the answers to it, but it was important to start thinking of these challenges early in my career. My marketing and distribution stint at Emerging was followed up with a 6-week editing course at The Edit Centre in New York. I hadn’t seen myself as an editor till then, and the course gave me a lot of confidence to trust my own creative instincts – which is something one doesn’t get to do as a 1st AD.

The next leg of my scholarship was as the Assistant Editor on Slumdog Millionaire in London. Looking back, the entire scholarship experience opened my world into thinking globally. Sitting on the editing table for Slumdog was a great learning curve. I learned from Danny (Boyle) and Chris Dickens about how structured the process of editing can be, and yet you can leave room for creative play, have fun with the footage and music and create magic. I think I learnt from watching Chris Dickens how to create a mood and feel with editing. I had the opportunity to sit in on a few music and mixing sessions and I will never forget those days with A.R. Rahman.

What brought you back to India?

Recession.

That bad?

Yeah, after the scholarship I spent a year in London in 2009. It was a very tough time for me personally. With recession at its peak, it was impossible to find projects. Looking back, I realise I didn’t have the experience to compete in that job market. All my savings were drained, I had to borrow from family – something I hadn’t done in ages since I had been working right from my college days. I moved back to India feeling like a complete failure. It was perhaps the hardest point in my short career. A few months after moving back I met Ayesha, who had a production company called Jamun. The company was going though some changes and I joined her as producer. We started out making small-budget films that were socially relevant, yet had strong visuals and high production value.

You mentioned you were working since college…

I was studying History at St.Stephen’s College and was an active member with the Shakespeare society (the dramatics society of Stephen’s). Somehow I got roped into doing a few voice overs. And it was so much fun and such easy money! During my second year, I auditioned for the role of an anchor for this BBC show called Wheels by Miditech. While working on the show, I realised what it took to make a TV show happen. I had a chance to write the script of a few shots here and there – and also had the embarrassment of seeing myself on TV! I realised I wasn’t cut out to be in front of the camera anytime soon, but I was very curious about what goes on behind the camera. That sparked a curiosity in television for me.

Is that what sparked your interest in cinema?

Not really, my love for cinema happened much later. It started with theatre, then TV. After Stephen’s, I applied for a Masters at JNU for International Relations and a Masters in Film & TV at MCRC, Jamia. I made the list at JNU and was on the waitlist at Jamia. JNU seemed like an obvious choice at the time.

I did attend JNU for a week or so and loved it for its politically charged atmosphere. But that was it. I liked everything about JNU expect the classroom – international relations felt too academic and too similar to my degree in History. So I decided to take a break and visit my parents who were then posted in Dubai at the time.

While in Dubai, I heard I’d made it past the wait list at Jamia. There was much drama in the family about what to do. I finally decided to go with a film degree and to withdraw admission from JNU – I had to get a total of 14 signatures and it involved some mad running around. I suppose it was totally worth the trouble, as Jamia opened up a whole new world for me. There were professors – like Varun Narain who taught communication through puppetry, the likes of Shohini Ghosh, Sabina Gadihoke and Sabina Kidwai – remain huge influences till date. It was at Jamia where I learned how to think critically and how to question pretty much everything. Stephen’s had a rich academic environment, but at Jamia the thinking developed was one that enabled me to use my degree in History to study Film Theory. Jamia had a diverse set of students from all walks of life – I may not have felt it then, but I really do value my years there.

How relevant do you consider a degree in film today?

Totally redundant. The future, in fact the present, of any kind of film education lies in workshops, work-attachments and online tutorials.

Any work projects during Jamia?

Yes, I did host two shows on AIR FM. That did subsidise my existence. Working early wasn’t a thing in our country back then but it is immensely helpful, and I’m proud to have started early. Post Jamia, I did work on the sound and lighting design on the theatre circuit in Delhi. The Delhi Theatre Circuit is a great place to learn stuff, expect at the time it didn’t offer much monetarily.

I worked on a few documentaries and worked my way up to land a job as the 2nd Assistant director on a Mahesh Mathai film, one of the India’s best advertising filmmakers. This was for his film “Sacred Thread”(later renamed Broken Thread) and that’s how I got introduced to Pravesh Sahni – who is a mentor to me and to India Take One Productions. This company has pretty much shaped my film career since. India Take One has produced almost all of the foreign film assignments I’ve worked on till date.

I must mention that you’ve worked on films such as Viceroy House, Victoria and Abdul, Slumdog Millionaire that portray Indian in an “unflattering” manner…

Yes, I am aware of all the poverty porn these films are accused of. Films like Victoria and Abdul and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel are films made for an international audiences. There may be valid criticism on how they portray India but the learning from these films for me was crucial. On both the Best Exotic films I felt like I was a confidante to John Madden. He’s probably the director that I respect the most out of all I’ve been lucky enough to work with. At times, I was more of a cultural sounding board for all things India. The Dark Knight Rises shot in India for not more than a 5-minute-long scene. But the knowledge there, and the exposure to Christopher Nolan and Wally Pfister – one has so, so much to learn from them.

You’ve also worked with Indian crews and celebrities for commercials etc – how has that experience been?

I’ve haven’t worked on Indian feature films yet, but have worked with some of the great names in Indian advertising: Bharat Sikka, Ram Madhvani, Shimit Amin and a lot of international commercial directors as well. These projects have formed some long-lasting friendships and relationships.

This varied experience is bound to have shaped your vision for Jamun.

Yes, the focus at Jamun is to try and find Indian stories that need to be told. We look to tell ‘real’ stories through high-quality films and bring a professional work ethic to the sales of projects. My role at Jamun is of a creative producer and my partner Ayesha Sood is the creative director. In the past, Jamun has done varied commercials, campaigns and music videos. We did a podcast about the Aarushi Talwar case I’m very proud of.

Digital media platform Arré commissioned a podcast that would dissect the murky complexities of the Aarushi Talwar murder case. We take on a lot of commissioned work in order to develop and fund our own slate of original content. We’ve set up a Writer’s Room to develop original fiction and non fiction content that we are pitching to a whole range of streaming platforms.

I’m keen Jamun turns out some great investigative documentaries in the near future, particularly related with false cases and wrongful accusations. We’ve been working on a seven-part anthology on inheritance and family. I’d certainly like to do something in the space of art and design. I also would like to see us do more podcasts, as they are on the verge of booming. The potential is huge.

What are your views on documentaries in India?

Globally, it is a golden age for the documentary. I mean look at the likes of Chef’s table, Wild Wild Country, Searching for SugarMan. In India, I feel the documentary still largely comes from activism and that needs to change. It needs to be thought about with the same core production values as fiction in order to get the attention it deserves. We made this documentary for the India Art Fair that looks fantastic and was picked up by Wallpaper Magazine. Our cinematographer was Swapnil Sonawane (the cinematographer of Newton) who shot the documentary on an anamorphic lens – not too many people are doing that in India at the moment. We need more Indian documentaries and things will change – they have to.

And your views about the general state of cinema in India?

We’ve been seeing some exceptional cinema out of India in the last 5 years. I can only hope it becomes the norm, not the exception. You know India for the longest time has been suffering with the limited menu problem with movies. Audiences have been offered two-three staples and nobody trusts things that aren’t on the menu – one assumes there’s no market for it. But how does one know if it hasn’t been served?

But it is all changing: look around, audiences are waking up and taking notice of quality cinema. Some films I’ve loved in recent times are Band Baaja Baaraat, Masaan, Mukti Bhawan, Titli – and many more. One that stands out is Titli and the way it treats the idea of masculinity in India.

Speaking of masculinity, you did a web-series for Mensxp that has generated a lot of buzz?

Yes, we did this 8-part series called Toughest Men In India. Everyday you hear of men getting bashed in India, including in this very Jamun office. Mostly, this is warranted. My partner, Ayesha, is a strong feminist and has been a huge influence on me as a producer and particularly on how I see women in cinema – on screen and as crew.

The show is for a men’s lifestyle portal called MensXp – they have a massive reach and are now moving towards meatier content. One cannot deny that there are good men out there. And we need them to be role models – not always role models in the Salman Khan and Cricketers kind of way. We filmed with a war photographer, a firefighter to Bollywood’s leading stuntman. We spend endless amounts of research to curate a list of such men. Many of these men broke down during conversations to reveal a sensitivity and empathy that’s never included in the popular narrative of masculinity. In a way, our lens for this series wasn’t masculinity but quality storytelling that celebrated these lesser-known professions and men.

I would love to plug the films here, I am extremely proud of producing each and every one of them:

Altaf Qadri, War Photographer

https://www.facebook.com/mensxp/videos/2302277469798522/

Nagendra Singh, Fireman

https://www.facebook.com/mensxp/videos/2293187720707497/

Amrit Pal Singh, Stuntman

https://www.facebook.com/mensxp/videos/2314215708604698/

Mahesh Verma, Maut Ka Kuan

https://www.facebook.com/mensxp/videos/2324957060863896/

Sundar Gurjar, Para Athlete

https://www.facebook.com/mensxp/videos/2336485019711100/

Sanjay Gehlot, Safai Karamchari Union Leader

https://www.facebook.com/mensxp/videos/2347852901907645/

Dr. Khizar Ahmed, Emergency Physician

https://www.facebook.com/mensxp/videos/2370668396292762/

Chappe Negi, High Altitude Mountain Rescue

https://www.facebook.com/mensxp/videos/2382157021810566/

What do you have to say about the current narrative of the nation?

Perhaps we are in a state in undeclared emergency, perhaps we live in a social media echo chamber? But I think one can’t deny that attacks on personal freedom and the press are on the increase. If you pick up the papers, democracy and the idea of plural India is under a heavy threat.

None of this is going to be resolved through Twitter warfare and online rage. I’m hoping for the liberal elite to participate more in democracy in some ways. I think we have failed to protect and ensure dignity and freedom for the weakest and we are more divided than ever. Yet, when one travels deep into the interior of India, the problems are real and beyond political left and right – they are about poverty, equality, rights and healthcare. They are about survival.

The danger is that most of the censoring and violence today is either state sponsored or has the blessing of the state. 70 years and we still fan the Hindu-Muslim debate for political gain. But lives are lost. And that’s tragic and criminal. I sometimes blame social failure as equally as political failure. We all need to take responsibility if we want anything to change. Even though you have journalists being shot and killed and films being censored arbitrarily, it’s important for storytellers to take a stand and be heard.

Perhaps there is no better time to be a filmmaker in India.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.