By Priya Bhattacharji

“Old school: A positive appellation referring to when things weren’t flashy…were done by hard work, didn’t pander to the lowest common denominator, and required real skill.”

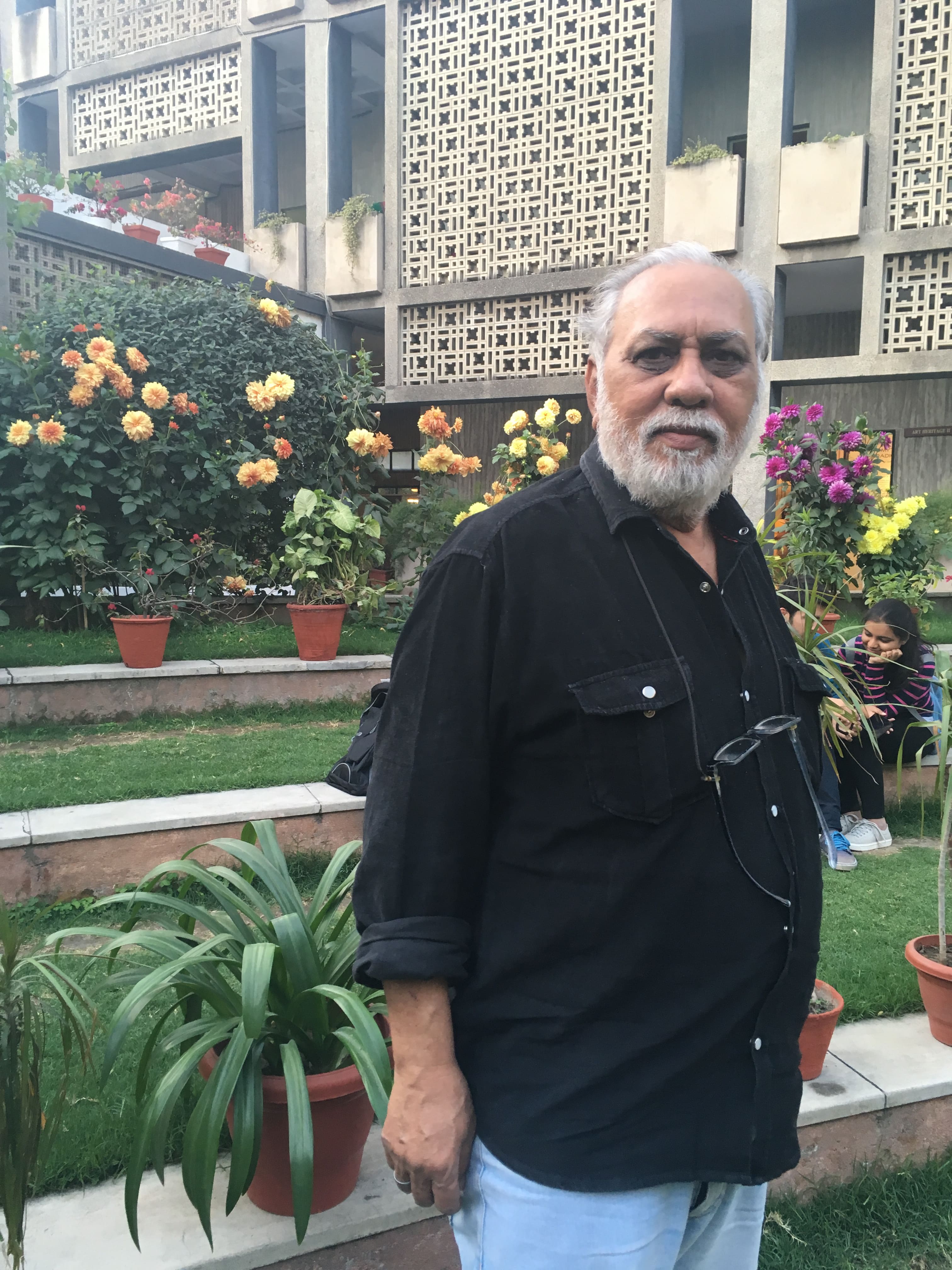

In true millennial fashion, my quest to find the true meaning of “old-school” stalls at Urban dictionary. It’s a phrase used by noted actor Lalit Behl to describe himself and substantiate his reason to chat in person, instead of electronic communication.

“I know people do interviews over calls and mails these days. But I’m a little old-school, I prefer to see whom I am speaking to, and would rather strike a connection before an interview”.

He signs up for a conversation at quaint Triveni Terrace Cafe at Mandi house, the renowned theatre adda in Delhi. While Lalit Behl narrates his fascinating life-experiences with avuncular charm, for me the interview transcends into an enlightening didactical session on the rigour, patience, and diligence required to develop one’s craft.

Which city do you personally prefer, Delhi or Mumbai?

LB: Having spent a lot of time in Delhi, some 30-35 years, I feel more comfortable here. In Bombay, I try to adjust to the way of living. My son, Kanu, is based out of Mumbai. In fact, I’ve often thought about why the film industry is not based in Delhi. Given that so many North Indians work there, why can’t it flourish in Delhi?

In Mumbai, the film industry earns so much, yet the government hardly does anything to support it. Log keedo ke taraf kaam karte hai…it is especially tough for people in the lower-rungs of the industry, the ones who have an invaluable part to play in making films. Only a few enjoy the benefits of the film industry. I get that after Partition there was nothing in Delhi, so the industry moved to Mumbai. But today, Delhi is in a good position to absorb the film industry. I often wonder why the industry can’t move here and thrive in the open spaces Delhi has to offer.

Isn’t there already a film city in Noida?

That’s been taken over by news channels now. The idea wasn’t executed properly. Chotte chotte studios se film industry nahin banti. It’s certainly called a Film city, but you need better infrastructure and facilities for an industry to thrive. I often wonder why the UP Government doesn’t actively pursue this. It is a big business, especially in today’s times where you don’t need to worry about post-production labs. I think it’s high time Delhi-NCR looks at it seriously. Call the top 5 Hollywood studios here, give them huge plots. The Yamuna area has ample space, a film city can easily be developed if the infrastructure exists. Even the music industry, for that matter. Mumbai mein chotti chotti galiyaan mein bade bade singers jate hai.

Those are some fancy dreams for Delhi.

Dreams are there. Dreams are big. Everyone needs to dream, else you’d never be able to achieve half of what you desire. Chand ko chune ke liye aap kuch kilometre bhi chale jaate hai woh bhi aapne aap mein ek chotta mukam hota hai. There are small, big, medium ways of treading life.

Has life taught you that?

Most definitely. I was born in a small kasbah in Punjab. The first 30 years of my life were very unsettled. I grew up in Kalka, a small town near the foothills of Shimla. My family had migrated there from Pakistan during the Partition. My father was a railway employee, and he was struggling to locate a position and place for himself. When I was nine, I lost my father. I was the oldest son and suddenly at the young age, the entire responsibility of running the family was on me. Koi bank balance nahi tha, koi makaan nahi tha…sadak par honi wali baat thi. We had to vacate the Railway Quarters after his death. However, I do still have a few impressions of my father. There was a local dramatic society in the Railway Workshop where the Ramleela used to be organized, as well as short plays and dramas for kids. My father used to direct plays and act in them. He used to take me along and I used to do small roles. I used to love acting, I used to love watching them. After his death it stopped and I pulled into the rozi-roti struggle. My family kept moving cities in search of employment. We’d stay with relatives, I had started doing odd jobs – in nut factories and paint factories. It was a disturbed period, but I managed to somehow study and get a temporary job in the Railways. I’d work two to three jobs at one go. I’d finish work at a factory and then work at a shop. I’ve even worked as a tea server for late night shows at cinema halls. All I knew is that I had a family to take care of, and so I took whatever came my way. Ajeeb ajeeb se kaam, alag alag kaam kiye. Yeh sochne ka waqt hi nahin tha kya accha hai kya bura hai. Koi option hi nahi tha, kuch kaamana zaroori tha.

That’s quite a lot to handle at such a young age.

I kind of became a father figure of the family. I did it all to keep the family together. Even today, I stay in a joint family. My brother, sister, mother and I still live together in Delhi. My son is based out of Mumbai and I shuttle between the cities. In fact, I’m sure I’d be in better position had I moved base to Mumbai to pursue my career.

Anyway, returning to my early life, once I got a job in the government, things stabilized. I was based out of Kapurthala and that’s where my interest from theatre was reignited. I happened to walk into an audition. I had to perform the character of an old man when I was twenty. It was an adaption of a French Play which was about three prisoners. I played the role of 70-year-old crook, who happened to be the central character. We started performing quite often and ended up getting the Best Actor award in any small competition we’d enter. It gave me a lot of confidence and energy. Professors started taking interest in my talent and grooming me. They were all in touch with world theatre of that time. I remember there was Professor V.D. Sharma, who eventually shifted to New York for his Ph.D. He’d give me books on dramas and plays of Samuel Beckett. This way I got acquainted with the new forms of theatre – Broadway included – that were evolving. Most of it would go over my head. Nevertheless, it was a kind of education in itself. In the meanwhile, I started doing plays on radio. I must have done 100-150 plays on the radio, but there was hardly any money in it. I use to get 30-50 paise cheques. But I was simply happy that I was getting to do what I want. Unn din radio mein kaam karna bada fakr ki bath thi. My interest in drama grew and I ended up not finishing my graduation.

Then did you decide to pursue drama seriously?

I started a small theatre group in Kapurthala with a few friends. We decided to perform the modern plays we read individually. It got people interested, as till then they had witnessed only Punjabi Theatre. Our theatre group was doing something new. We were finding new idioms. There was no method to our acting; it was purely on passion. We used to travel to Chandigarh to watch the modern Indian cinema that was evolving at the time. Watching the films of Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak helped us sharpen our skill set and broaden our knowledge. Slowly, I learnt of the National School of Drama and the theatre movement there. We then began travelling to Delhi to attend theatre festivals. We did our best to keep abreast of the theatre and cinema of our times, and read what was being written about them. Iss tarah humara theatre group maqbool ho gaya tha, log humari ticket kharidne lage aur paisa collect hone lage. With revenues coming in, our theatre group decided that every year it would fund a society member to study drama somewhere. I tried applying at NSD and FTII for acting, but I was not selected. Still, I somehow kept myself deeply associated with the theatre scene and tried to introduce modern sensibilities to people around. That was an education, too.

Any members of the theatre society who shaped you or influenced in some way?

Hmm. One of my colleagues went to study theatre at Patiala University, and that’s how we formed an association with that college. He had a female theatre professor there. At that time, few women were associated with theatre in Punjab. One of our plays demanded a women lead and my friend recommended his professor. She joined our group and started taking part in plays. I was the head of the theatre society, so we struck a sort of camaraderie. That progressed and that professor eventually became Mrs. Behl.

Wonderful. And how did theatre evolve from a passion to a profession?

That took a while. For a bit, I had to leave Kapurthala in search of a more lucrative profession. I had this perpetual sword dangling on my head – my sisters’ marriage. I was never afraid of doing anything new. So to earn some quick money, I was advised to join a foreign Merchant Navy. I left my secure Government job and went abroad. To be honest, I had to smuggle myself. I went to Russia and then to Turkey. I happened to find myself a job on a ship that allowed me to travel 80-90 countries in a year. I was walking the streets of Istanbul on the European side and met this guy who was working for a ship that was sailing to London. London had been a dream for the theatre lover that I was. I somehow managed to get on this ship. When the captain discovered me aboard, he was compelled to give me a job. My tryst with London is quite a story and I will not divulge the details. All I can tell you I had to sneak out of the ship to go and watch plays around Soho. The tickets were costly but I managed cheap ones. In fact, I had flown Aeroflot while travelling to Europe. When I was in Russia during transit, I visited the Moscow Art Theatre. This way in a matter of a year, I travelled places, got to watch international theatre and earn a lot of money. Finally the ship came to Calcutta and I hopped off. I had saved around 80-90k, which was a lot of money at that time. I got my sisters married and shortly after that, I too got accidentally married.

Accidentally?

Long story, and it took us both by surprise. I was jobless and wasn’t even a graduate. She was a lecturer, a Ph.D no less, a daughter of an IAS officer who was also a known playwright.

I, on the other hand, had nothing to my name and had a lot of responsibilities. She was Sikh, I was a Hindu. There were a lot of differences. But marriage is when I started life afresh. In the first year itself, our son Kanu was born. She had her job in Patiala while I was directing plays in Chandigarh and had begun to make money. I used to get contracts to direct college plays that paid reasonably well. Staying there was a problem. Then someone suggested enrolling in a course to get hostel accommodation. So I joined a course in Indian theatre, got a place to stay and had an income. My wife insisted I complete my graduation, which I did through correspondence. Not only did I become a graduate but also a gold medalist in theatre.

What brought you to Delhi?

I was advised to move to Delhi not only to pursue theatre further but also as a safety measure. I had directed a few college plays that were against the Khalistan movement of the time. I was threatened by the extremists. Both professors and police suggested I shift base. I moved to Delhi and joined the Shriram Repertoire. My wife and son used to come visit me on weekends. Soon, I got to perform Willy Loman, the central character of Arthur Miller’s Death of A Salesman. It was quite a challenging role for me.

But you were already an established stage actor…

I couldn’t find this guy’s roots. It was an American play where Willy Loman was a product of a liberal economy where people lived a fast life. I was performing this in 1980s India. We were a socialist economy then and liberalization hadn’t happened. It was a tough and difficult character to play. I also learnt Dustin Hoffman was playing the role of Willy Loman. This was after ‘Kramer Vs Kramer’, for which he had won an Oscar. He had paused his film career to return to theatre to play the central character of the play. When he was starting out, he had a minor role in the play. For me that was huge boost to be performing that same character. Anyway, the way I portrayed the character was well-received. Some NSD people asked me to try for their Repertoire. That’s how I got to work with big names in theatre. I did a variation of roles, from a comedy with Barry Johns to Tughlaq. I got to work with great talent and it was quite a learning experience. However, in 2-3 years, there was stagnation and no scope of growth for me. Bade bade namo mein aap chotte ho jaate ho.

Is that how you began your career in television?

I forgot to mention that around the time of my marriage, Doordarshan came up. At that time, in Punjab, people got to watch Pakistani TV channels as they could catch the signal from Lahore. In Jalandhar, a Doordarshan studio came up and they approached me for a TV serial they were planning to produce. It was a Punjabi TV series, Sapnoveyn Parchavyen (Dreams and Shadows). I got the lead role because I was a popular actor in Punjab back then. It was a 26-episode series, each episode an hour long.

People don’t know about it because it was regional, but it was India’s first TV series, way before Hum Log. When I moved to Delhi, TV was looked down upon in the theatre circuit. So I used to do it on the side, slyly. People in theatre were largely of the belief that one who should overlook money in pursuit of true art. TV was associated with quick money, and people who worked for TV were seen as outcasts. I was called for a role for Hum Log, but at the time I was under contract with NSD. But once I hit a saturation point in theatre, I started working as a freelance actor. Television had more money; salaries at NSD and Shriram were negligible. It was impossible to run a household. I got a role in a series called ‘Aisa Bhi Hota Hai,’ that turned out to be a very popular show. Kids used to wait for it like adults waited for Mahabharata. It was the first Indian series in which on-location anchoring took place – an Indian version of Ripley’s Believe It Or Not. Once we did an underwater shoot while covering the city of Dwarka in Gujarat. I got to travel around India in search of amazing places and stories.

How long did it take to shoot in those days?

It took a lot of time because of the technicalities. It took one and half years to do thirteen episodes. The Punjabi TV series I mentioned was relatively swifter: 26 episodes in 26 weeks, as it was studio-based. Still, it was a challenge, as there was no concept of editing back then. Everything was shot in one go. Actors had to put a whole lot of effort into the rehearsal process and adhere to a strict behind-the-camera movement design. Also, we used record in Jalandhar and it was transmitted from Jalandhar. There was this looming tension to send the reel by taxi to the transmission studio on time. Only when it was telecast on the TV, we’d know the tape had reached safely. By the grace of God, all the serials were successfully made and transmitted.

How do you think that compares with the current day scenario?

Today, shooting is very easy. Even a young kid can shoot on a mobile phone. But I have to say: the sheer effort that used to go into shooting those days had a value attached. I’m not complaining that shooting has become less stressful or tension-free, but the easier it has become, the more signs of deterioration we see. TV was very different those days.

How did you go about selecting roles when you began work in TV?

After I left NSD, I really couldn’t find something that excited me as an actor. Dramas were usually shot in Mumbai, infotainment like Aisa Bhi Hota Hai was shot in Delhi. Then I thought, why not start something myself? The idea was to bring the drama of theatre and cinema to TV. Most people who shot TV serials had film experience. People like B.R Chopra and Shankar Nag worked for Television, which is why the quality was very good. Competing and walking besides such stellar talent was a challenge in itself. So my wife and I devised a concept and wrote a script. This film was called Tapish. No one was talking about the Punjab problem. The subject of the film revolved around the psychological impact of this political turbulence on the common man. It was at its peak in the late 80’s. People appreciated seeing it being talked about on TV. Then my wife and I proceeded to make films for TV – Chirryon Ka Chamba, Rani Kokilan, Happy Birthday. We made them one after the other, and then we started getting TV series. Afsane was one such series, Ved Vyasa ke pote was another.

I think I remember Afsane. My grandmother used to be hooked onto it.

Yes, I directed it, my wife wrote and acted in it as well. It was about a migrant Bihari couple who lose their daughter as a child. They end up tracking her down when she’s twenty, yet due to various circumstances they do not reunite. It was a story that people loved a lot.

You never ventured into cinema then?

I did a lot of films for TV, not cinema. My wife did a film called Maachis with Gulzar Saab. He had liked our film Tapish and the way we dealt with the Punjab problem. As an honour, he called my wife and me to act in the film. I couldn’t take it up as I had an assignment. My wife played the character of Tabu’s mother. We did get a few offers from Bombay cinema, but they never matured because of our commitment to TV in Delhi. I know it would have made sense lucratively, but our emphasis was always on the quality of content. We never compromised on that. We never worked under the constraint of “2 din mein shoot karna hai.” Agar dus din kaam par lag rahe the toh lagne dete. We were more bothered about creating a product of quality that our audiences would appreciate. Our life wasn’t bad, but we weren’t exactly rolling in money. Although we did plenty of work for Television, we were living hand to mouth. I started taking up some advertising and event management assignments, and that’s how we ended up buying a house in Delhi.

How did Titli happen, besides the fact that it was directed by your son?

Kanu used to participate in the films we made, as a child actor. He assisted me in a few shows. You could say he got an ‘in-house grooming’. He went on to pursue a direction course in Calcutta.

After the course, he decided to move base to Bombay in 2008. The kind of films he’s associated with has our marked influence – the realistic work we did for TV is reflected in his work. He assisted Dibakar Banerjee there on LSD, Oye Lucky Lucky Oye. Then Yashraj commissioned Titli, a film he had written. At that time, I was burnt out and had decided to do nothing. TV had been conquered by the Ekta Kapoor element, humare kaam ki qadr nahin thi. Our audience had drifted away. I wasn’t too keen to do the character Kanu had offered me. You could say I was kind of scared, but somehow I was made to agree. Na-na karte karna pada. I wasn’t even given the script. I was asked to act from scene to scene. It wasn’t drastically different from what I had done before. The camera was different, but the atmosphere was more or less the same. Working with my son wasn’t a big deal. I worked in the capacity of an actor, followed his instructions. I enjoyed it and enjoyed seeing my son play a competent director. I refrained from giving him suggestions. I didn’t interfere in the process of making the film.

What about Mukti Bhawan?

My character in Titli caught the eye of Shubhashish Bhutiani,the young director of Mukti Bhawan. In a few interviews, he has mentioned he created that character keeping me in mind. When he sent me the script, I didn’t see it for a few days. I ended up meeting him, and I was impressed with his intelligence and vision. Then I did read the script and realized that he had actually written it with me in mind. The experience of working on the film was fabulous. It was an extremely young and dedicated team. Shubhashish was clear about what he wanted in his film and I found it very inspiring. He’d never hesitate improvising, but kept within the range of the script. He created a wonderful, creative atmosphere to work in. Nobody was working for money. It was made on what they called a ‘love-budget’. The film was made with a lot of love.

What do you think the resounding success of ‘Mukti Bhawan’ spells for independent cinema in India?

It does signal a change in a fresh crop of cinema. In my lifetime, I have witnessed many waves of independent cinema. There was the era of Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen. That was one phase of Indian independent cinema that travelled far and wide. Then there was the era of Shyam Benegal, Basu Chatterjee. Even in commercial cinema, the likes of Bimal Roy, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Gulzar brought in what was called the ‘middle wave’. It was beautiful and inspiring time for cinema. Personally, this period inspired me a lot. These directors have had a huge influence on me. Somewhere at the back of my head, I wanted that my work should be in the same league. It was the middle-path of cinema. It lacks ugly commercialism but yet isn’t rukha-sukha cinema, the kind no one wants to watch. Right now, a new wave in taking shape. Young directors are bringing in new ways. The medium is expanding. This is necessary for growth.

What are your new projects, your vision for personal growth?

Predictably, after Titli and Mukti Bhawan, I get offered many generic ‘old man’ roles, which I shun. I have completed work for a web-series for Amazon Prime called ‘Made in Heaven’ directed by Alankrita Srivastava, who made Lipstick Under My Burkha. Never in my life have I run after roles. I have done whatever came my way. I did the same when I was in theatre. Life has invariably made me climb rungs, but I was never in a race to reach the top. Whatever work I do, I want people to remember it. My works are like my children: close to my heart, made with a lot of labour and love. I love it when people appreciate my work. For me, it’s not about the money but the appreciation.

I’m not in the Bollywood race of having a fancy bungalow or charging large sums for the roles I take up. There are so many talented people, raring to make their mark. You’ve to give the audience a reason to remember you. For that, you can do two films or you can do a hundred films. For me, the fact that I have made an impression with Titli and Mukti Bhavan is a huge thing. I’m not ambitious to do many films. I’d rather do memorable ones. That’s my idea of achievement. I know I have done good work in theatre and played an important role in TV’s golden period. More importantly, I know I have done work that doesn’t embarrass me. At the end, I’m a simple minded guy who left his kasbah in the hope of better work.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.