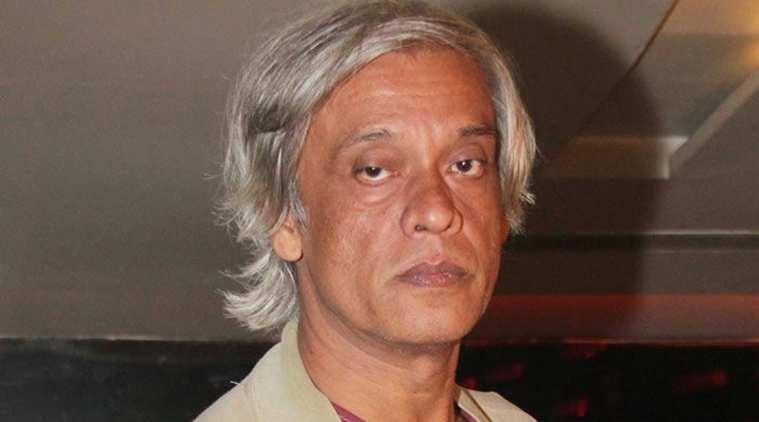

For many of us ’80s kids, including the ones who run this website, 2005 was the first time we discovered the legend of SUDHIR MISHRA. Little more than a decade ago, after watching a strangely effective and largely ‘niche’ Bollywood film named Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi, an entire universe of possibilities opened up. During our formative years of cinema appreciation, Mr. Mishra’s filmography — which we soon visited with the eagerness of a child discovering the magic behind a trick — changed the way we thought about and looked at Indian films, little by little. Though his latest efforts haven’t quite broken paths the way his initial titles did, the filmmaker retains that aura of independent omnipresence. He is nowhere, and yet he is everywhere. His long-awaited next, Dasdev, isn’t too far from the news either.

CHINTAN BHATT tracks him down for a quick chat about his early years, the evolution of ‘parallel cinema’, the importance of Bombay, the recurrence of time as his favourite narrative device, and much more.

I was watching your first few films, Yeh Woh Manzil To Nahin, Main Zinda Hoon, Dharavi, Is Raat Ki Subah Nahin — all of which were so distinct from your later work, a distinct peak into the cultural/sociopolitical aspects of the places they were based in. How do you look back at them now?

SM: I don’t know, I have never been a conscious sort of filmmaker. I come from a certain background. I am a mathematician’s son and my mother’s side is steeped in a political background. I think there might be an early influence of this childhood in those first 3 or 4 films. I came into cinema at the fag end of the parallel cinema movement. For example, if Mani Kaul, Shyam Benegal and Kumar Shahani are the beginning of the so-called ‘parallel cinema’ in Bombay, we are not talking of Ray who came before in Bengal. I am the last person in this line. With Dharavi, (it felt like) last of the well-known people who made an actual impact on cinema. After that, cinema ends, and you are in the market. And if you want to continue to make films, the state is absent, and cinema is decaying. There is no structure to cinema anymore; you put in 6 songs, make a comedy, and do anything in between. The arbitrariness of the so-called “Bollywood structure”, which some people write theories about, is actually structured by the music companies. They want a fixed amount of songs, they want music videos: go shoot in Switzerland, give me a film, don’t upset any traditional values, but titillate people in the beginning and also, just in case these random restrictions aren’t enough, the underworld also comes in to have a say. Let’s be honest: we are making films at a time when the underworld is dictating the tastes and language of the movies that are to be made. Within that context, you have to somehow make films and still retain the integrity. For example, during Is Raat Ki Subah Nahin, somebody told me, “I don’t give a damn what you make, just put in 6 songs, I have a music label.” So I just put these songs in between the structure of a narrative and made a film which I wanted to make. That film reflected what was happening in Bombay at that time, which, in any case, I was facing even in cinema. I tried to stay afloat and then, I got a bit tired of it. So if you see Hazaaron, it kind of reconnects with what I was doing.

You came to Bombay when you were around 22 and your life before that was spent mostly on college campuses. Do you think that outsider objectivity helped you in those early films?

Yes, I think so. Persians say the best film is the one that combines what you have seen and heard with what has happened to you. In that sense, Dharavi is a film about a man coming to Bombay; he is from Uttar Pradesh, getting fucked in the head. So it is his relationship with the city, which, in turn, reflected my relationship with the city at the time. I just used the slum culture as a backdrop and objectified it with a taxi driver, because that helped distance myself from the film. When we came here, we lived in those tough circumstances. And I kind of liked Bombay also because I grew up on a campus and a cosmopolitan atmosphere, not specifically in one culture. One of my uncles was a Tamilian Professor, another was a Maharashtrian and a Professor of Physics. There were Nigerian, Palestinian and Malaysian students. There were people from Kashmir, Kerala, and even the locals. So I think I took to Bombay because I was not used to living with one specific section of people. I discovered Bombay to be a city where people are allowed to change the screenplay of their lives; it’s a city where you come and disappear into anonymity and you can emerge as anything. Or you can disappear and get lost totally. I liked the fact that I was a nobody, because if you have an upper-caste background from a smaller town, you are always somebody. Hence I connected with my essential self in Bombay, there was nothing else that was hindering me from what I wanted to do. There was no sense of family and belonging, or worries about who would say what to me. There was a freedom, an odd sort of detachment and freedom, which I experienced for the first time I came here.

It was then that you met a lot of filmmakers here like Ketan Mehta, Shekhar Kapur. What do you think is the difference between the filmmakers back then and the modern ones now — at least as far as the basic selection of stories, approaches are concerned?

There were all sorts of filmmakers I liked. I really liked Ketan when I came here; there was a notion of the world back then, predetermined and at times hopeful for the future, like some kind of possibility of change through cinema. Many of those naïve hopes, which I think got shattered later on. And the parallel cinema movement also ended because the wall collapsed, because the Soviet Union dismantled. So many filmmakers lost their ‘the ends’, people could no longer hold hands and walk into the sunset — what happens at the end of Garam Hava, what happens at the end of many films with the inherent hope of a screen going red. But I think I survived because I was a mathematician’s son, a scientist’s son. So for us it was not ideology, but a methodology. You look at truth in its objectivity and you don’t flinch from it, and whatever happens, happens. So the end of Hazaaron is what it is. We find solace in personal and smaller things and hold onto some vestiges of beauty that are left, but the idealism has collapsed. Another idealism will find its place, something else will happen, and some things will remain.

And I like the younger gang today. In popular cinema, people like Rajkumar Hirani are very interesting. I like the work of Anurag (Kashyap) a lot, too. I also like work of Vishal (Bhardwaj), Anand Gandhi, Sriram Raghavan’s Badlapur, Ritesh Batra’s Lunchbox and many others. I like Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s ambition. He believes that realism is not the only form of good cinema and I think he is right. But some day if it all comes together and he stops worrying about the audience, I think he will make a great film. Bhansali, with regards to craft and understanding the medium is very interesting. Also there is a kind of ‘Hollywoodisation’ of the industry. Cinema is now reflecting the aspirations of the state, of India as a power, and Indians taking on the bad guys. It’s interesting how the contemporary bunch interpret this, because the world is very confusing right now, and I think very few people grasp it. Every now and then, there will emerge a kind of filmmaker from India who will grapple with this complicated world we are in.

The compulsions of previous filmmakers and today’s filmmakers are the same, except that they have to handle it in a practical way. There is no State; it’s not like you are in France where the State subsidises your work, they give you money to write a script, make a film, and occasionally they give you money to release it. This acceptance of the State’s interpretation of culture (at times, against its own agendas) in the general politics of a country is absent here. For obvious reasons. The youngsters have to grapple with that absence of patronage. And how they handle this forced independence is the main question today.

Ek Raat Ki Subah Nahin and Chameli were based during one night; Hazaaron used time in years beautifully to convey emotions, and Inkaar also played with time. Is there any device like time which has stayed constant throughout your films, especially since Ek Raat Ki Subah Nahin?

Sometimes, the real essence of things is captured in a moment, and if you catch people in a time of crisis, that moment reveals itself. Time goes backward or forward, but it is only in the head of the audience that you truly understand it. In Iss Raat Ki Subah Nahin, there is a past, and there are also things that will happen after and before the night, but it all gets compressed. And Hazaaron is actually a very Indian film, with an Indian notion of life, very sufi, where everything is taking place in the present simultaneously. That’s why I called it Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi. Critics who liked it didn’t ask why the film, which is based in the emergency, is named that way. They didn’t go: (we) don’t think Ghalib was the hero of the people at the time. Ghalib is my viewpoint, inside me and allows me to look at life. Mohabbat main nahin hai fark jeene aur marne ka, ushi ko dekh jeete hain, jis kaafir pe dum nikle. That’s my idea of the film, and how I look at it.

Think about it: In cinema, everything is happening in the present, so I don’t think there is anything called a “period film”. Or, everything is a period film. So it’s about capturing life as it ebbs, capturing deaths at 24fps, because as soon as you finish shooting, that time is gone forever. When the film is over, it’s already about the past. Some films have to begin earlier, some films later, subject to the impulse of what you set out to make. Chameli is about that moment when two people meet, Iss Raat Ki Subah Nahin is about that simultaneity when two completely disparate people are in a crisis. Khoya Khoya Chaand I quite like too, but people don’t talk about it.

I can go on talking about Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi forever, but I wanted to ask you why you chose English as a language for much of that film?

Language is also sound. I was trying to talk about two different places in India. Otherwise students would have been speaking the same language as villagers; so when it’s about the use of sound design, it’s about the use of English language too. Also language is more of a gesture, it’s an attitude. It also dictates your worldview in a sense. If you talk to a Dalit today, Dalit intellectuals will tell you that they don’t allow their kids to learn Hindi, they want them to learn English because English doesn’t have words that demean them. And also that Hindi, Urdu, other Indian languages have words that demean them.

I was just trying to create a soundscape. I thought we managed, and I knew it was not the commercially correct thing to do, because there was so much English that it almost became like a linguistically “non-Indian” film. But that’s what I thought was the issue at the time — there was an ideology coming from somewhere, Leninism or Marxism or this Stephanian attitude. And in India, the language of the privileged and the language of the people is different. Again, nobody has delineated that (while watching), and nobody has talked about why English, because the counterpoint itself says something about India. Imagine if I put in Hindi instead. So many scenes would lose their meaning altogether. When they are talking to each other, they are almost talking in some sign language; Siddharth is trying to understand those Dalit guys who are trying to save the life of the landlord they came to kill. The incomprehension of these guys, a trained mind not understanding things, it’s all a part of the counterpoint (which I thought was) necessary.

While making Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi and working with those actors, did you feel that something interesting and different was happening or was it business as usual?

I had a feeling that something was going right. I don’t think it was some special chemistry between the actors. But I think it was about the people I put together; something just clicked. Shiney kept telling me while shooting that I was never expressing his love, and that I should take a close-up of him when he looks at her, and I just told him that the moment I do that, it would all fall apart.

It takes you to the tipping point and then leaves you there without actually giving you the melodramatic push. Even the editing is designed like that, across spaces and time.

Yes, something happened. Every filmmaker will make 3-4 films in his life that he is actually meant to make. And only he can make it, the rest will be a build-up and preparation for the eventuality. I think I have made 2 films like that, Dharavi & Hazaaron. And I think Khoya Khoya Chaand too, but let’s see. Time will tell. And now, I also think DasDev (the flipped version of Devdas). That’s 4 already.

Often in your films, a male character is enamoured by a female character, which pretty much sets up the film. Like in Chameli, Hazaaron, Khoya Khoya, and even Yeh Saali Zindagi. Are you aware of this trait and do you think it’s a subconscious tendency while you are writing/making it?

But all of us are compelled by that irrationality. In Hazaaron, Geeta (Chitrangada Singh) has something for Siddharth (Kay Kay Menon), Siddharth has something (his ideas) for villagers and Vikram (Shiney Ahuja) has something for Geeta. That’s what keeps them connected and human. The rest of it all is, you know. So I think personal is the metaphor for something more interesting.

Was Geeta in anyways based on Anuradha Ghandy or someone else from that time?

No, I don’t know. There were many like that at the time in Delhi. This is about a generation. That is what I said in the beginning too, right? That this is about people ten years older than me. I grew up listening to many people like that. I don’t exactly know where it has come from. But it is, for me, the first generation that unlock themselves from the predetermined notion of why they were and how they should be. Some people say Aruna Roy, some people will say Dilip Cherian because he wrote a book later. I don’t think it was consciously based on anyone. I tried to keep it within my imaginative space because I didn’t want to get stuck in anybody else’s story.

The inevitable entry of politics into your films…does this happen at an initial stage or it seeps into the story later?

This is how I am (smiles). Political is a way of understanding how we are enslaved, whether by organised religion or the State and forces that control the state, or by market forces. Understanding how you are enslaved is a political act, the first reaction is you try and find an escape from it. So that’s how I am, the being of me. I don’t do it consciously, but the film tends to move with it.

You never worked with Jacques Bouqin who shot Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi again?

No, he wasn’t well then. I got to work with Jean-Claude Brisson also, the sound guy. He later did Motorcycle Diaries. They were quite senior, and it was a good collaboration.

You have had a long association with DOP Sachin Krishn after that, who has shot many films for you.

We understand each other. It’s the kind of a thing where you come in, you look at a scene and talk around a scene, and he tends to get it, after which he seems to add a bit. There is a comfort, where you become like an extension. I like it.

What interests you today? A story or a world with interesting characters or themes?

Basically it’s people on the margins who are disassociated from the mainstream. The problems of the minority in more ways than one, and not just a religious minority. People who are trying to extend the boundaries of what life has laid out for them, whether a taxi driver from Dharavi or the student of Yeh Woh Manzil To Nahin, or the whore in Chameli, or these 3 in Hazaaron, or the gangster trying to comprehend what he is doing in Iss Raat. I think if my films specifically differ from most other filmmakers in the idea of the ‘hero’ it merges. Somebody called my film the “anatomy of greys”. I think it’s in trying to figure out what really is heroic, because even the men have a feminine side to them, a slightly softer side which is not that ‘macho’.

What do you think of current use of literature in Hindi cinema?

I definitely think that the relationship can be stronger. I don’t think it exists much in Hindi cinema. In Tamilian regions, Kerala, Bengal it has existed. But in Bombay, I don’t think it has. Literature can give you triggers or areas, places, people (with) which you can travel (with) and explore. But you cannot be bonded to what the author tried to do, you have to find your own way of doing what you do. I think it’s absent in Hindi cinema.

What do you think of the current state of film criticism?

I will tell you honestly: I like critics. I may sometimes not agree with them, but I like any critic who looks at my film deeply. Whether s/he likes it or not is secondary. But at least he has bothered to look in a way that if I read him I can find an analysis of it. I am just making and not over analysing stuff, but if somebody can make me understand (parts of what I do) then I would welcome them. A lot of creative people have this problem with critics, but I kind of like them. Critics are graceful people who spend time on other people’s work. I like critics and producers (grins). A good producer and good critic is, of course, the best thing for a director.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.