Something strange happened at the screening of Kenny Basumatary’s Assamese comedy, Local Kung Fu 2. To my pleasant surprise, most of the viewers were Mumbai-based Assamese friends, collaborators or colleagues of the director. For them, this was a local event – a playful reminder of home in a faraway city.

Over the next two hours, I laughed at various points of the scatterbrained Martial Arts caper. My subtitle-reliant guffaws usually preceded theirs by a few seconds, like mild lightning before heavy thunder. I’d quickly read the translated subtitles, and chuckle before the line is fully delivered, while they chortled at the inflections and flavour of their own language, the timing, linguistic nuances and delivery of the phrases. At times, however, when the silliness of the action became dominant or if a Hindi-speaking character played the fool, this lag disappeared. Our smiles synced.

We learnt about each other simply by reacting to the film, without exchanging a single word.

That’s the thing about Basumatary’s indie. Unlike most Indian regional films, its innocence is very inclusive. It isn’t so much about the language as it is about the feeling of comedy it employs. It educates us about its culture by not really trying to; the towns are Guwahati and Tezpur, but the faces seem to be mocking their own traditional mundaneness. It’s a spoof of action, a parody of comedy as well as a good-natured joke on our preconceived perception of alien lifestyles.

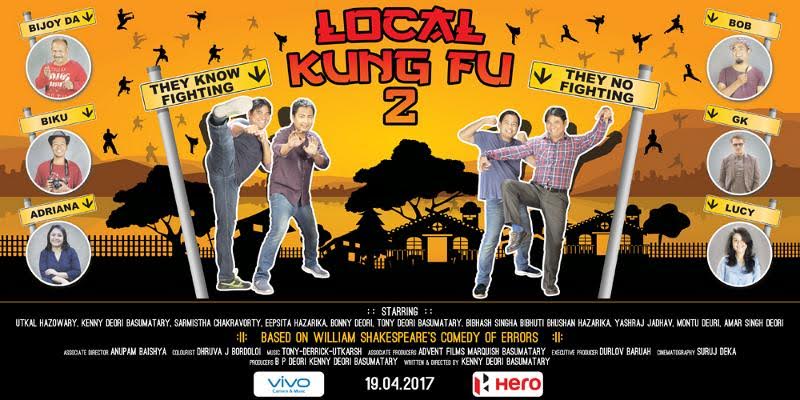

The theme of boring environments turned into a madcap Shakespearean Comedy of Errors is not something you’d expect to see as a low-budget independent venture conceived entirely in Assam. Which is why it thrives on us being blindsided. We’re meant to be consistently confused; the mistaken identities (one “action-hero” set of best friends unknowingly stumble into the surroundings of another “domestic-drama” set, who’re actually their identical twins separated at birth), crowded narrative and double roles are supposed to be a mess. The plot is meant to be ludicrous. We’re meant to mentally be lost about who is who, just like the secondary characters (a suspicious wife and sister-in-law, a fraud Baba and his two idiotic minions, and a hamming bunch of rival local mafia gangs) of the film are.

Even the dynamics of the extended fight sequences are somewhat symbolic of the film’s inherent everyday-ness – a fit Basumatary, who also plays one (two?) of the Martial Arts duo named Deep/Deepu, often aims for a clumsy leg-lock of his opponents, while a stocky and stiff Utkal Hazowary, the second of the duo named Arun/Tarun, is far more smoother and dangerous with his moves. Majority of these contests unfurls in bungalow backyards and untidy gardens. The best part about this subversion is that it seems un-choreographed, and extends itself to the smallest of moments – like a hyperactive gangster leading his men across town, only to be temporarily stopped in his tracks by traffic on the street, or a fighter poking the wrong part of his opponent’s body while threatening to target a particular organ.

By the end we find ourselves cackling at things we’ve stopped admiring in mainstream potboilers – heightened characters, goofy caricatures and nutty situations – because even the filmmakers are. Their fun is palpable, like an invisible laughter track peppering the absurdity of their own sequences. Not once do they feel the need to resort to an unnecessary emotional crutch. Everyone is having a blast in a behind-the-scenes sort of home-video way. And most of us in the tiny hall felt invited.

Funnily enough, the only issue I had with Basumatary’s equally colourful 2013 prequel was its lack of technical finesse. Here, this style somewhat contributes to its irreverent mood; the clumsily dubbed words, cartoonish expressions and non-professional actors form a sizeable part of the whole charm. Like a Kung Fu Hustle or Shaolin Soccer, Basumatary manages to tread a fine line by making a professional and carefully assembled venture look hilariously unprofessional.

After the screening, a blooper reel accompanied the end credits. We stayed back and giggled as if the film were still on. In a way, it was. This time, the infectious people on screen laughed just before we did.

[This review was first published on Film Companion]

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.