By Harsh B.H.

When we jump into Haraamkhor, two 12-year olds are ogling a slightly older school-mate of theirs. A little while later, we jump into the scenery of their fantasy – that of a perplexed young girl, Sandhya, and her tuition teacher, Shyam. Sandhya has a father who goes off at night citing ‘official’ work, while Shyam, by the looks of it, seems to be his students’ — especially the girls — favourite eccentric disciplinarian.

We stay with them for a while, then we come back to the 12-year olds, Kamal and Mintu, who, as the film takes great pleasure in informing us, have just learned how to wipe their asses but are none-the-less mighty curious about the birds and the bees already. So whose story is Haraamkhor about?

The audience isn’t wrong in expecting to be informed in clear terms who the protagonist is. But like any self-respecting Indie, Haraamkhor too isn’t willing to give us the satisfaction of a straight-forward narrative. It tells us two separate stories, no doubt. But unlike other multi-track narratives, these two take place in the same vicinity. They’re simultaneous and intimately bound, despite being made like two parallel films. Perhaps this is what sets Haraamkhor apart. Like a curious child, the narrative hops along from one track to another, and director Shlok Sharma juggles his two tales with great fluidity, merging them into one engaging, all-encompassing narrative.

Some occasional plot-devices do come off as too convenient, like Sandhya bumping into her father’s ‘friend’ in a distant town, more so because the rest of the writing remains fairly non-formulaic. But they do not bother us for too long because all the while, Haraamkhor keeps us busy with its colours and quirks while seeking a sense of coherence and emotional charge. We act patiently with the mildly haphazard structuring and the wandering narrative, because Haraamkhor is an uncompromising indie in the truest sense of the word: from dripping with a grainy picture quality (which it wears like a badge of honour) to having a cameo appearance by a fellow film-maker who himself is struggling to get his first release.

And besides the structure, Sharma sets up a bizarre world to prop up his storytelling. This universe is occasionally surreal in its imagery (a naughty kid forever dressed as Shaktimaan because…well, just like that), mostly filled with cultural references that evoke a time gone by – old-fashioned cameras (where photographs had to be ‘developed’), no trace of cellular phones, the Shaktimaan obsession (of course), a rickety Luna stacked inside a compound (only for urgent chores, perhaps).

And yet, the film never comes clean on what time period it is set in. Just when we assure ourselves that it’s the 90s they’re occupying, a boy throws in a ‘Dabangg’ reference. We also never get a clear picture of the kind of rural area it is – it surely looks like a nondescript village, but big enough for two fellow students to not be aware of where an attractive classmate resides, or small enough that a teacher feels comfortable groping her student without having to bother to look around twice. Sharma’s world is either anachronistic or refusing to confine itself to one specific era or space.

Haraamkhor can also be read as a film about gender-battles, an issue that never refuses to escape our lives – it after all unravels in a world where the amount of injustice you are prone to is directly proportional to whether you are a male or not. The two boys get away with their recklessness because they are boys, who someday will turn into men. They are the ones who run after other people’s coins when they fall – while it’s the girls who help collect them back and organise them into neat rows, only to be rudely told to move to the next item in their list of duties. It’s a world where girls turn to the first male figure showing affection in absence of a functional father figure, only to be exploited even more.

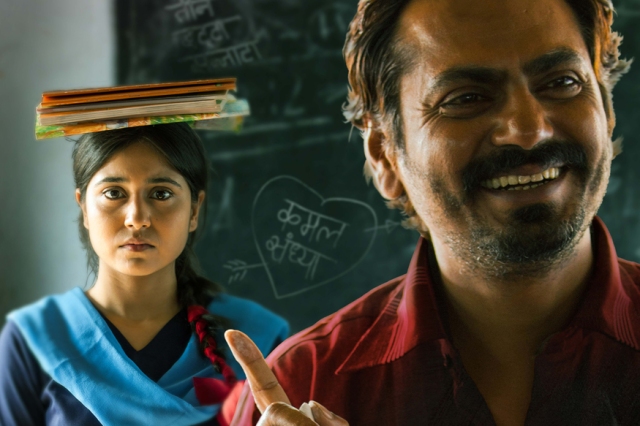

Nawazuddin Siddiqui had only recently appeared in a negative role in Raman Raghav 2.0, but here he paints a different shade of villainy, distinguishing this character from the sociopath that Ramanna was. That was manic, this is pure machiavellian. However, it is the 26-year-old Shweta Tripathi who accomplishes a genuine feat – that of looking the part of a 15-year-old school girl, in this age of over-marketed physical transformations. It helps that Tripathi has a naturally dainty presence, but it takes much more to build a character that feels fifteen too. It’s not make-up but the lack of it that Tripathi uses to her advantage, and chalks out that clueless, wide-eyed rusticity to her Sandhya without being too obvious.

So while the teacher-student story holds you with its portrayal of blurry lines between morality and desire, it’s the sequences with the two 12-year olds, Kamal and Pintu, that really reveal thematic undercurrents and arrest your attention – not just because they are naturally amusing, but also for how they manage to remind us of the horrific proceedings unraveling in the narrative, while freewheeling away from them simultaneously. From turning a newly broken home into their personal playground to pondering about what it takes to get married while jumping over each other, the two float away in their wonderfully imagined and sexually charged fantasies – where they build their own theories around two people, and write the story suiting their fantasies.

At some points, Haraamkhor is reminiscent of Nagraj Manjule’s Fandry – which had two young boys, too, living in their own bubble, far removed from reality – whose world revolved around a potential love interest. The only difference between, Haraamkhor’s boys are lot less romantic and much more frivolous. We laugh at their innocence, but part of our laughter also comes out of the nervousness that stems from seeing these two kids get so dangerously close to adulthood in all the wrong ways. This is frivolous adolescence at its peak – and I don’t remember the last film where child characters came this close to being loathed by the audience. Their obsession is not harmful, but naive and unburdened by any awareness of reality – which is what makes the story both heartbreaking and unsettlingly funny. They do not fully comprehend the consequences of what they are doing, but we do.

Sharma often revels in creating visuals that juxtapose the naivety and horrors of adulthood – Sandhya playing video-game while going for an abortion, the two boys jumping over each others’ feet while talking about how perhaps exposing genitals to a girl results in an eternal union (they are all of 12, mind you…or not even that old, perhaps). Haraamkhor thrives on this dichotomy, and can be enjoyed best when seen as a quirky love triangle, where the three involved belong to drastically different stages of life – because it talks about kids wanting to be adolescents, and adolescents craving for a slice of adulthood.

But it is essentially about this curiosity that only childhood can contain. The plot kicks off only because a character is curious about where her father goes off to at night, in the guise of perpetually serious demeanour and ‘official’ work. The boys obsessing over Sandhya is their desire to grow up quickly. And what else is Sandhya’s attraction towards her teacher, if not a desire to be an adult, a curiosity about what it feels like to be a grown-up?

This lends a strangely circular feel to the narrative, which is when you somewhat make sense of the title – as you realise everyone in the narrative is exceedingly curious about what the other is upto – more often than not, coming across as mirror images of each other.

The only one who stands apart from these bunch of voyeurs is Meena, a friend of Sandhya’s father whom he had kept secret from his daughter in the opening portions. When we first see her, we get a sense of what her relationship with Sandhya’s father is. Here, Sharma almost provokes us to judge Sandhya’s father as well as this woman – who never found it important to introduce herself to his daughter. Slowly but sheepishly, she attempts to break through Sandhya’s initial hostility. Only gradually we understand her own backstory, which is marred, not unlike Sandhya’s current trajectory, by disloyal men who cannot be trusted. She senses Sandhya’s unrest without judging or imposing her own step-motherly wisdom upon the girl. No wonder then, that in this universe of reckless wild beings, she is the one Sandhya politely asks for a hug. For Meena – in a world where others are too busy faking sadness to woo their wives back into marital normalcy, or try out macho naked poses lifted from movies – is the only one worth a hug. And for judging her initially, we deserve the titular role as much as most of these characters.

(The author blogs about films at https://allaboutbombaycinema.wordpress.com)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.