Very often, in a country like India, the intentions of an artistic piece overshadow the actual piece. If this isn’t deliberate by the makers, the media and vague discretionary forces torridly combine to relegate filmmaking to just another vapid political statement. One frets that, somewhere deep within these cauldrons of publicity, revolutions and reactions, the craft itself gets a bit lost — like a puppy unable to finds its way home. But, where is home really? One can only tell, or at least navigate the closest map, by exploring the meat — its centre most point of conflict, revelation and truth — of the work in question.

In a film, one would have to pick out perhaps the most defining phase or moment, and then analyse (or feel, or react to) the amount of honesty in its storytelling and craft. There’s always that particular moment, which, you know — while it’s going on — will define and endure, and you hope it moves you, you hope it doesn’t fall flat.

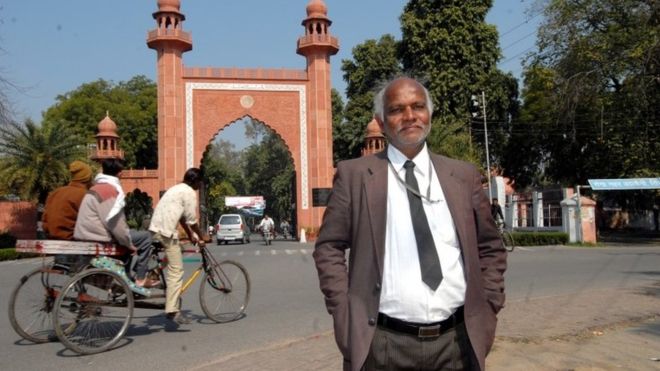

In Hansal Mehta’s ‘Aligarh’, there are multiple moments like these. Most of them involve Manoj Bajpayee, the actor essaying the role of Ramchandra Siras, the Aligarh Muslim University professor who was suspended in 2010 after being caught in bed with another man. But the bed was his own, and this was to happen behind his own closed doors, until he realised that two overzealous TV reporters had forced themselves in with a camera to record this. Clearly, they were tipped off, and disturbingly, he was being spied upon. This was in violation of the law. He died after the 2-month long case, only days after it was ruled in his favour, and his position was reinstated in the university. There were traces of poison in his blood, arrests of other university officials were made, but nothing was ever proved. The young journalist that broke this story — Deepu Sebastian, then with The Indian Express — had never actually met him, but the filmmakers thankfully give the story a bit of a face by letting them (Rajkummar Rao, as Deepu) meet, and forge a reluctant, unlikely bond.

Their relationship is vital to the film, and the film’s most endearing and deepest phase comes when they’re chatting during a mid-afternoon boat ride. This is towards the end of their journey. Siras hates labels, and explains to his young friend why love is a far more complex — and abused — term in today’s world. Bajpayee does this in a very non-judgmental, intimate and hurt tone, as if he is tired of being offended by it, and he doesn’t want Deepu to speak like that — just like he wouldn’t want his children to use bad language. He wishes the day were longer so that he could be himself and wax eloquent about poetry (“the pauses”) once again. The other parts of the week are spent following people reluctantly — his lawyer, activists, LGBT functions, acknowledging support — when all he wants to do is live with dignity. He bashfully blushes and mumbles when he is asked to recite his poetry at a small farmhouse party, and for that minute, his habitual whiskey peg is being used as a catalyst of expression. Till then, it was a crutch of loneliness.

By now, Deepu and Siras relate to one another silently; Deepu is ambitious, restless and has been living in a noisy rented room (PG) in an old lady’s Delhi bungalow. It doesn’t feel like home, and it shouldn’t, and he doesn’t even like going back to his room anymore, spending more and more nights at office. When he sees that Siras, too, has been forced to shift accommodations without a permanent address, and without many belongings, Deepu doesn’t want to end up like that 30 years down the line. Which is why he makes an effort to understand Siras as more than just a news headline. This flimsy sense of displacement actually brings them closer.

Siras is already deeply embroiled in court proceedings, and spends his time translating his own poetry book into a language Deepu can understand. Subconsciously, too, he is already doing his young friend an unconditional favour, because Deepu had once mentioned in passing that he can’t read or understand Marathi. It keeps him occupied and indifferent to the legalities of his own case. It keeps him, for those hours, an artist with plenty of time to interpret his own work, his own life and times. While translating the stanzas, he must have remembered the smells and sounds and sights and phases of life associated to the days he wrote them in — perhaps back when he was still a middle-aged man, leading a stable life with a wife and family. He finds his past in those words, and perhaps smiles wistfully at his own translations, hoping that they would guide a young man into his own future. Whenever you watch Deepu on screen without Siras, you wonder what the old man is upto. You wonder if he is still as lonely and tired. You wonder if he ever phones up Deepu to speak about the articles. Deepu, too, wonders, but he has a job, and he is looking for a better place to move into, excited about this transitional growing-up phase. Maybe those visits to Aligarh will reduce, now that Siras himself is traveling quite a bit because of the case.

Eventually, you come out of ‘Aligarh’, the film, hoping that Deepu wasn’t disillusioned by Siras’ death. You hope that he had no regrets, and didn’t blame himself for thrusting the old man into the spotlight. You hope he become a fine journalist, spurred on by this tragedy, a trial by fire — a professional who would still look for humanness and personality and intimacy in his “subjects” and stories.

But, more than anything, you hope that ‘Aligarh’ remains a powerful film, an unnerving reflection of the times we live in, instead of it being used as a deliberate sign of protest — a game-changer designed as the need of the hour — against many flaws of this country. It makes you think about a citizen and his/her right to privacy and sexuality, and in some cases, it makes you act, but you don’t want its makers to tell you that you *MUST* act and must contribute by simply watching and feeling their heartfelt film.

Thankfully, the film is bigger than its parts — and it leaves us with a sense of having watched a documentary, with enough questions, like any good, well-researched and sincere dramatic account of true events.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.