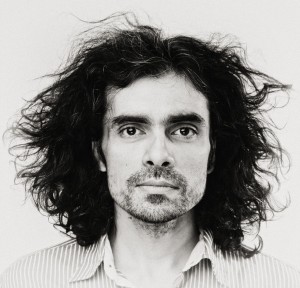

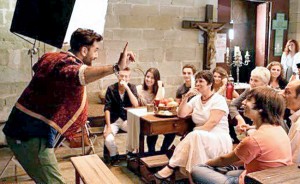

Perhaps the most dynamic mainstream filmmaker in Hindi cinema, Imtiaz Ali has constantly pushed the boundaries of storytelling. Not everyone is comfortable with it, and his films probably evoke the most extreme reactions, but one can’t ever accuse him of being in a ‘comfort zone’. He is responsible for some of the most memorable on-screen protagonists in recent times – Geet in ‘Jab We Met’, Janardhan/Jordan in ‘Rockstar’, Meera in ‘Highway’, Ved and Tara in ‘Tamasha’ – and is constantly in search of the complexities that plague (Indian) relationships and life. His narrative techniques have arrested imaginations, as audacious arthouse parts of a commercial whole.

Here, the director sits down with CHINTAN BHATT, and talks movies, philosophy, literature, collaborators, music, criticism and opinions. And like his movies, he doesn’t hold back.

A bit about how your journey began?

IA: I left Jamshedpur and went to Delhi for college. Those 3 years were largely dedicated to theatre, in college and outside college with a group called Act One in Mandi House. After which I came to Bombay, because I thought it to be a more dynamic and better place to work in. I did a course in Advertising & Marketing at Xaviers Institute Of Communications (XIC) so I that could get a job. But I didn’t get a job. And then I got a job at Zee Tv which had begun at the time to create content of its own. That was, in many ways, the beginning of it all.

You’ve told stories the way you want, and the writing – so many facets – has been different in each of them. What’s your process like?

IA: Ever since I was a kid, I would get my friends from class together and tell them you say this and I say that, and so I would end up directing them and I would write at the same time. While in theatre, there was hardly anything I had written and not directed, and vice versa. And when I got into direction full-time, it so happened that I again wrote and directed. Ultimately, by the time I got into movies I was still trying to get someone else to write, but then because of budget, time or both, I could never quite afford that option, and I had to write what I was directing. Now 6 movies down, it has become the same thing for me. I feel fortunate actually that I work like this. I do collaborate with people too.

But I don’t really know what the writing process is. I don’t know whether it is to imagine something in my mind and jot it down as notes to myself. I think I write like that. And much of what I write might not make sense to a lot of people. But at least in directing the movie, it will make sense to me and I will remember everything I had thought of. And usually what happens is I write on the computer – I write it like a novella. I don’t worry about what the structure is – not bothering whether things are falling into a montage or a scene or song. I don’t care, I just write it down. And then I keep working on it till it fleshes out more and more and more, and then much later, scene numbers and all those formalities get included.

I read somewhere that you write your first draft in English.

IA: Sometimes. Very often actually. So it can happens in English and I translate into Hindi, and sometimes it comes in Hindi itself. So I don’t bother about writing it in English just for the sake of formatting. It can be anything because mostly only I – and nobody else – have to read these in between drafts.

One hears a lot about how your films are about man-woman relationships but they’ve worked (for me) more as individual characters with unusual connections. How do you look at them? Is it all chemistry for you, or is there more to them?

IA: No, I don’t know what chemistry is. I don’t think chemistry is a word that signifies anything as far as stories are concerned. I feel that a lot of people, who look at movies, look at actors and what’s happening between them not as characters. I, as a filmmaker, am interested in characters. So even when I start making a movie or even after ending a movie, I don’t look at it as a love story at all. It is a story. In my stories, there is usually a guy and a girl who form what serves as basic relationships of the movie, but the purpose is not to make a love story as such, ever. And from the little I know, I don’t believe in genres and categories and classifications too much. I don’t understand all that and I don’t want to. I feel that every time I have enjoyed a film, I have not been worried about which genre it has been in as a viewer. I have simply thought, “this is a very nice film and I loved it”. If it is a fuck-all film in any genre, it’s not going to work for me. So I look at my movies like that too. And many of those films I feel, like Jab We Met and others, it’s not a love story – because in a love story the whole struggle of two people to be together should be the main thing. I don’t know. Everything is a love story or nothing is just a love story, for me.

There is a lot of optimism though coming through by the end of most of your films. Are you inherently optimistic and those are personal choices or you think those are good ways to simply end those films?

IA: No, I feel that life gives you more reasons to be optimistic. I feel that not only because the movie needs to end at a certain pitch; it’s more to do with the fact that it is very difficult to imagine a story which ends in a way that makes you feel bad. This comes across as that optimism, and I feel it. Even Rockstar, the film ended in a way that this character was unhappy and you felt his sadness, but sometimes you have sadness or tragedy in performing arts because that is also enjoyable. But yes, mostly I feel that life gives us reasons to be optimistic.

There is always a sense and passage of time in your films, maybe except ‘Highway’. Time during which characters go through epiphanies, changes, evolution…

IA: I think time is the most precious quantity anybody can have. You can never hold it, can never have more of it no matter what you do. I also feel that time sharpens you, it changes you necessarily – and when you change, you look back on your own principles and agreements you’ve made in your life, and you realize that you don’t believe them in the same way. New beliefs have sprung up, old beliefs have fallen by the side and that you are constantly re-defining yourself. So time re-defines the attitude of people. And that is important in a dramatic way (to explore) in my stories.

I have had people in my life where I had that real connection with some people. No matter how much time passes, that feeling does not change. Time almost becomes irrelevant whether I meet them again or not. Do you think that irrelevance of time also comes across in your films?

IA: I think so. Time becomes irrelevant, and I believe that. In Tamasha too, all those years pass but nothing changes. That’s true.

In your Q&A after Rockstar, you had talked regarding the non-linear structure, that for musicians their past often affects their present life, decisions and creativity. How do you look back at Rockstar and its structure, and was that thinking behind Tamasha too?

IA: I think both Rockstar and Tamasha couldn’t have been completely linear because there is presence – especially in Tamasha – of the past. The past influencing everything, the past not dying, the child remaining within you and not being killed is the issue. So you needed the past to be present, which means that the film can’t be completely linear. Same thing with Rockstar – the mind of the person who was the protagonist would fluctuate, would not be the linear clear-cut way of thinking at all, which is why the jumble and chaos. He processed information like that. So that’s how it became the narrative of that film.

Can you talk about the influence of literature in your work? Philosophies like existentialism come across in your films quite often.

IA: Existentialism comes across not just because I have studied about it. It also shows because of why existentialist thought came into the world for the first time, which is because you see that kind of thing around you. At some point of time, you start questioning the meaning of your triumphs. Existentialist thought exists because it is very relevant, also encountering causes which created existentialist literature directly. It’s more that, than the reading from books actually. You try to find meaning. And when you try to find meaning, sometimes, you feel that triumphs are pointless or not as significant as the journey. Even to say that a journey is more important than the destination is an existentialist thought, which often is a thought seeded in my stories. “MANZIL SE BEHTAR LAGNE LAGE HAIN RAASTE” is a line in the song from ‘Jab We Met’. So apart from existentialism as such because I am a literature student – I am an English Literature student – and even before that, I was aware of and used to be interested in literature. Whatever little bit I would read would make an impact on me. Not that I keep it in mind, but I am sure the way I write and the way things come out have some sort of influence of the early masters like Shakespeare and the way Greek theatre uses chorus. I feel that I tend to use it like that in economising time, in representing the points of views of people.

Literature has clearly had a lot of influence in me. At least I am aware of what goes out in the world. But I don’t read it as a ready reference for the work I do. In fact, since I have started working more and more seriously, I have started reading less and less. But I do also understand, being a literature student, that literature does not have a pre-established form. When Shakespeare was doing his plays, he was an actor or a director and the writer, so he didn’t think he was making literature. But now he is the biggest name in English Literature. I feel that cinema is contemporary literature.

The thing about Jab We Met that struck me most was – when the girl leaves the guy, instead of him breaking into a sad song, he in fact celebrates her memory which inspires him and makes him happier. That’s there in ‘Heer To Badi Sad Hai’ a bit too. This treatment comes automatically when you are writing, or do you realize the chance to be innovative in such situations?

IA: It comes automatically when I am writing actually. Often, I write a certain way and then figure out why I wrote it. So I chiefly write it like that. Because I am myself bored, I won’t write something which makes bores me while writing it. So I would be bored if he comes back and is weeping etc. I feel in case of Aditya in Jab We Met, Geet was never his; she never promised him anything, and he started to like her, and then he left her. I feel that the choice is there with you. It’s the same thing as the glass half-empty or half-full scenario. You can take something positive back out of a love-relationship. Or you can quote the tragedy, that will also emanate from a love-relationship. But anything that is passionate is positive. Those must be the subconscious reasons behind why, while writing something which is conventionally tragic, doesn’t come through as tragic. And the character chooses to be optimistic about the way he is feeling and enjoy that feeling and live with that.

Your use of montages in songs – the way you take your characters and stories forward through them – is pretty unique.

IA: I think the nature of the movie dictates the musicality of the movie. Rockstar had montages of a certain kind – a very rockumentary state of mind – pieces which were playing with music almost without a purpose, but with some passion. I feel that as I am spending more and more time with movies, I am realizing that the unspoken word is the most cinematic because it uses the language of cinema. Of music, sound and all of that. That is something I think has been changing ever since ‘Love Aaj Kal’. Then the nature of Rockstar, because it was the story of a musician and a person of a certain type who doesn’t process articulately, but he processes feelings and moods through music. So there was growth, because when you are actually shooting that, there is no reference of dialogue. There is no set precedent that one minute of any scene expresses this information. It’s not information that you convey. So that was an important thing for me. And in Highway, the same thing. The state of mind, you know. Sometimes, the day passes, the sun sets and at night you are travelling on the highway and you feel differently. No information has come in, nothing new has happened, but somehow you become a different person. So if cinema has to express that – how does it do so? Music becomes an important thing over here, because you will not have those seven hours of cinema time. You will have to express it in ten seconds or one minute; the music kind of creates a note that takes you there. And again Tamasha is what happens with a certain use of music. Because here you have a ‘Heer To Sad Hai’ wherein you are supposed to have a sad song, but you have a happy song. But the lyrics say that the person is sad. So it’s just a contradiction which creates this spectacle on the stage, which becomes the storyteller for what the story of Tara is. So it is a narrative technique where, on the stage some people are telling you the story of how sad Tara is after she comes back from Corsica, and what happens in her life in the next four years. But it is used to tell you a story in a happy manner, because this is Tamasha.

But do you think there is more of a ‘jugalbandi’ of screenplay, music and editing in your last 3 films?

IA: Much, much more. It also depends on the way the musicians work. Rahman sir sees the whole film as one. He doesn’t see it as separate song and separate music pieces. In Rockstar, we figured out the songs and shot them, and after I shot them we edited them and after I edited them I gave them to him. He wanted to have the visuals of the songs. So after the visuals are ready, he works on them with his music. He doesn’t keep making the songs in isolation of the visuals.

Is that why a lot of people like his music and songs much more *after* watching the films?

IA: That is the reason why. Because in the studio, there is also a screen, so while he is working on the songs, visuals play simultaneously. So it’s almost like doing background music work on the song itself. And there are many ideas that come out from this: I react, and ask, why don’t we do this for the film, because over here we can get a separate web of some other musical instruments, because this is the kind of shot, so he’ll do it in a way that he keeps it in the audio. The music develops along with the film beyond a point. There have been many times in Highway, especially where we have shot the song without the song with some conversation between him and me; I figure out how the sound is going to be and I shoot something like that ‘Tu Kuja’ song in Rajasthan. And sometimes, I use some other track to shoot a certain song which he then sees and then composes accordingly. In ‘Agar Tum Saath ho’, there was some other scratch. After seeing the edit, he decided to change the song – and he changed the song twice over to suit the visuals because he did not want a complicated song. We wanted a very simple song because the situation in itself was very complicated. So there was a lot of interplay between the visuals and the background music, which is why it gives you a sense of unison.

Can you talk about the association with editor Aarti Bajaj? Most of your cast and crew has changed over films, but that association has remained pretty constant.

IA: I think (lyricist) Irshad Kamil has been there from my first film too, and Aarti has been working with me from Jab We Met. She had not edited my first, Socha Na Tha. I don’t know why it is the case. Never really thought about it. I feel that in a process like editing, understanding each other is an extremely critical and crucial thing. When you are working with any other technician, there are also other people in that place. Even with a music director or a lyricist. There can be the music director when I am talking to the lyricist. But in editing, the director and editor are alone in a room, and there is no one else. So you need to have a very comfortable relationship, wherein you can say things to each other, understand each other so that no time is wasted. And to be very clear, direct with each other. It’s a very intense relationship because you have to work in complete isolation.

So the structure of Tamasha and Rockstar was all in the screenplay?

IA: Yes, the structure of all my films is there on paper. Those are writing decisions. Often, the viewer attributes the writing decisions to the editor, but that’s not how it is. But with Aarti, I feel a sense of comfort because there is nothing I can’t say to her. I understand her pretty well so we don’t have to worry about elementary stuff. Also I feel very safe with her because she is not one to bullshit anyone. She’d rather be blatant and call a spade a spade right to my face. She knows me for long enough to say YOU IDIOT COME BACK TO EARTH. I can say the same to her, it’s such an old relationship. Upto now, I feel she has always added value and brought some beauty to the scenes that are shot.

Tamasha is probably your most visually accomplished film. How was it like working with Ravi Verman? Was it a conscious choice to work with him because of the look needed for the film?

IA: It worked out very nicely with Ravi. He is the most energetic cameraman you will find, the most innovative and the most restless cinematographer who can really bring a certain value and power to the visuals. Also having worked with Anil Mehta for the last two films, I was so comfortable with Anil that I needed to work with a different mind. And again, the collaboration between the director and cinematographer is the closest or the most critical one for filmmaking. The best thing about Ravi is that we don’t understand each other’s languages very well, but the moment we start talking cinema, we understand each other perfectly. And he’s got a genius mind as far as filmmaking is concerned. Anil said that after making two films with him, I should work with other cameramen to learn new things. That is the reason I went for someone else. So working with Ravi Verman made me value what Anil had said.

What are your views about film criticism in the country today?

IA: I don’t read critics. I don’t read reviews at all. I find them very confusing; I often see agenda there. And whether or not anybody has an agenda or bias, I don’t really care because I don’t read reviews. The reviews take away, at least from me, the pleasure of watching films. I’d rather see the poster of the film which is the most important thing for me. I am not even into trailers much. So something in the artwork will get me to watch the film. So I don’t like or read reviews, and I don’t know if you’d like me to say that (smiles).

I am not a critic…

IA: But the guy who owns this (website) is so…Honestly, I feel that up till now, the way it has been going on is largely detrimental to cinema.

I read your facebook post which you wrote as some people took the whole corporate life criticism literally and seemed offended. Also, during Cocktail, it happened with Meera’s character that people took it as a statement of what women should be and took offence. Do you think some people just tend to compartmentalize and generalize what they are not comfortable with?

IA: About the recent post, after posting that, I realized that maybe there were only few people who were thinking of it so severely – that this is almost dismissive to people in the corporate world. That was just not my idea. I thought I would put it up to make my stance known. I think it is just very convenient sometimes to generalize, and lots of people do so, but not everyone. But I also can’t generalize that everyone is like that. There is a tendency in the society at times to follow the leader and avoid the responsibility of original thought. I think that is changing though.

As far as the other one is concerned, I don’t think people generalize everything, but somehow if there is a trend or a fad then it is easier to follow it. And then everybody says the same thing. I really respect people who have genuine thought, who have original thought, their own thoughts and are often wrong, but my respect will always be for those people. While in my training for advertising and marketing, I would ask people in the survey, YOU LIKE COLGATE (blandly)? And they would say no. And if I’d say YOU LIKE COLGATE (with a smile)? They would say yes. They are not thinking, just reacting. Why would they think so much about movies? For me as a director or for you as someone involved in the business, your opinion about the movie matters a lot. But if I am a regular person who has come to watch this movie for entertainment and I go away, I will not have an opinion. Then it is up to the media to generate an opinion, to ask those questions that prove that they are in the know or at least they wield a lot of authority over an opinion. But actually, things are so individual. Because every person who is an opinion maker is connected to another 100 people who are also opinion makers. So who says what in what forum – people are not really being very responsible and that’s good, why should anybody? It’s not like voting a government into power. Liking Bajirao Mastani or Dilwale? You know, who cares? Everyone is bothered about more important things in life beyond a point of time. So whether they liked Tamasha or they hated Tamasha, you don’t know, because it’s not uppermost in their minds. I don’t know what this was in answer to, but this is a tendency I needed to talk about.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.