Director: Arif Ali

Spoilers Ahead…

At times, when one doesn’t fully understand or grasp a film, we aren’t often afforded the luxury of going back to revisit each scene to identify clues or pick out things we missed the first time around. Short films allow this. After watching it once, you can play it back and perhaps savour (or diss) the details in shots, identify a graph, little music cues, expressions or even analyse the all-important plot point with greater attention. Some of them are not entirely intentional, but the limited duration allows you to enter the mind and decipher the thought process of the filmmaker more than most mediums. It is an unforgiving medium, especially if one attempts to explore a genre in less than ten minutes. Every cut and every frame becomes important, and there needs to be a narrative purpose to each of them.

Arif Ali’s PLAYING PRIYA is an example: you watch its 6 minutes, and then re-watch it to figure out whether you watched it attentively the first time. You try to find things that don’t really exist, before realising that the final twist is actually deceptively simple. We’re only conditioned to imagine over smart complexities in this genre. There is nothing to look for, really. The question is: if thrillers beg for a second or third watch, doesn’t that beat the purpose?

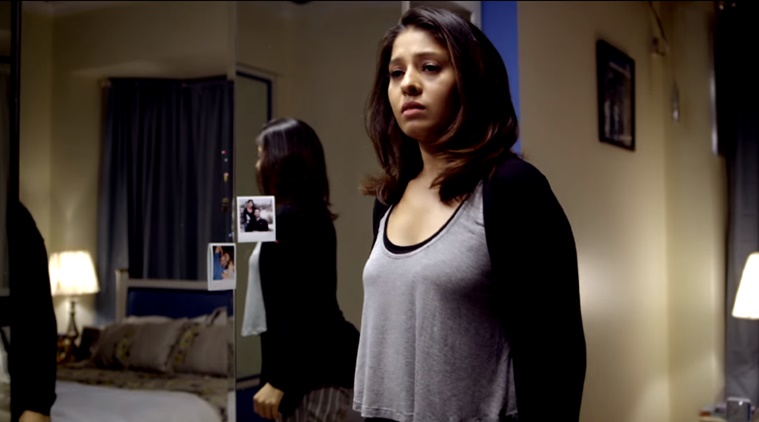

Playback singer Sunidhi Chauhan is Priya, a housewife whose husband (Mukul Chadda; one always wishes to see more of him) seems to have left on a trip with the kids. From the looks of it, Priya doesn’t get the house to herself too much. She savours this space, and decides to prance around and be a bit of a dreamer. I’m pretty sure most homemakers do this when their husbands, wives and families leave for a bit. Perfectly acceptable, no matter what age they are. Which is why, perhaps the director could have been more creative with Priya’s flights of fantasy: All she does is dance around a bit and experiment with hairstyles and faces in the mirror; this was Chauhan’s opportunity to showcase her presence, too, given that she has no lines in the film.

Any how, the idea is that this is her time, and she will enjoy the lack of responsibility and noise. Unfortunately, it’s after dark, and the bungalow is big — and ‘home alone’ often means only one thing in the movies these days (unless you’re Macaulay Culkin in the 90s). Her tomfoolery is interrupted by someone entering the house, and then her bedroom, after which she switches off the lights and hides in the cupboard. To begin with, the footsteps don’t really sound ominous. They sound rushed and legal, more like the husband returning to pick up something he had forgotten. So her very act of hiding sort of gives it away earlier than the filmmaker would have liked to (the money shot isn’t so surprising after this).

What follows next is vaguely reminiscent of Ram Gopal Varma’s KAUN (1999) — a classic feature-length exercise in paranoia, deception and urban distraction. The difference being: since Ali doesn’t have the time or incentive to play around with the viewers and his characters much, he resorts to the mandatory supernatural realm. In most cases, this seems a bit of a copout, but the intention here is to just be cheeky and be a step ahead, nothing too ambitious given that the tagline is “Your home is not the safest place.”

You’d think it was Priya this refers to, if this were still 1999. But 17 years and many been-there-done-that twist endings later, it’s quite obvious that this may or may not be her house. And she may or may not be Priya, evident from the phone call her husband answers when back in the room to pick up something. He is talking to (presumably, his wife) Priya. Which, in turn, means that the pretty ghost playing Priya is probably a method actress spirit practicing her roleplaying skills: she just likes to inhabit bungalows as bored housewives and pretend that being human is the best thing ever.

Maybe that’s what it is — it’s not a ghost who is obsessed with the husband (that would make it a Vikram Bhatt saga); it’s one that just wants to feel normal in a civilised world. What if she goes from house to house in every locality internalising its inhabitants to adopt her favourite persona? Though that has been done before in various Hollywood alien tales, the mundanity of this premise and its environment holds promise as quite a poignant unconventional urban-alienation tale. But then again, these are just many feature-length possibilities; the world is their oyster, but oysters are too expensive. And perhaps only I’m thinking about them, because maybe it’s my job to go deeper and explore its potential. Someone else could just roll their eyes and shut the link, annoyed at yet another simplistic paranormal crutch.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.