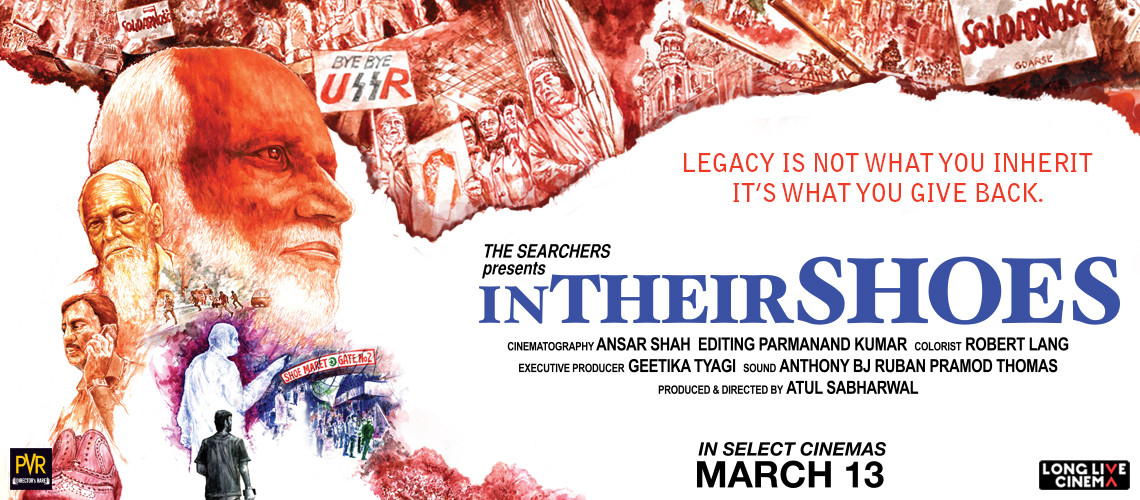

Director: Atul Sabharwal

Visually chronicling the history of a particular trade, commerce or entire empire is, inherently, a losing battle.

There’s not much a filmmaker can do to jazz up dry information. There are no live concerts or phone calls to capture, and no families to follow with a camera for years. However, between recreating eras through tacky docudrama setups, and simply piecing together a congruent story through verbose interviews and archival footage, I’d choose the latter. After all, as much as the telling of a story matters, the story itself comes first.

Atul Sabharwal’s (who has previously directed the almost-there ‘Aurangzeb’) documentary—chronicling the history of the Agra shoe trade industry—has the added advantage of ancestral involvement, thereby adding a tinge of intimacy to his images. We don’t have to worry about the authenticity of what he is showing us; but we must worry about the angle, racked as it is with the possibility of bias and personal involvement. In the end, though, the balance is somewhat there.

A necessary evil in such documentaries is plenty of exposition, verbose slates and tons of interviews. Not all of this is entirely relevant and engaging, but every now and then, a trend is observed. It is only appropriate that a filmmaker attempts to capture the mood of a dying trade he was politely pushed away from. For him, it is just a crucial piece of his childhood. Fortunately, it makes for a fascinating peak into a world not many are familiar with.

Sabharwal constructs it with the same rueful narrative you’d expect from an old-school director mourning the advent of digital over pure film. Here, it’s original leather versus quick fix ‘Chinese’ synthetic (foam). The music, invoking Reznor and Ross’ understated score for ‘The Social Network’, is minimalistic. Across seasonal images that paint Agra as more than just the Taj Mahal and a ‘mental hospital’, we are informed, in various tones of old and new voices, about how the fall of the Berlin Wall, export bills and liberalization in the 90s affected domestic trade, about how generational institutions had to adapt or perish.

I zoned in and out of this lesson, just as I would as a distracted child observing my father managing a boring denim business. It is fascinating for those involved in it, but what interests me—since I come from an entrepreneurial town that thrives on ‘foreign-return’ kids taking over family businesses—is a unique Agra trait: Foreseeing the dip in shoe fortunes, brave fathers discouraged Gen-next from taking over. That some were forced to return due to poor overseas economies is a cruel, but typically small-town irony. This reinstates my faith in the Indian family’s most primal form of selflessness, in this time of stubborn philosophies and misguided tradition.

Sabharwal’s father, one of many founding veterans who brought their skills from across the border, makes for a familiar, war-grizzled presence. The director’s decision to casually follow him through the market as he gently requests fellow traders to ‘indulge’ his son with a byte or two—the way only parents can, brimming simultaneously with pride and embarrassment—is a crucial one. “He is roaming around with his camera again so…,” he tells his friends, suggesting that they’re already aware of his ‘filmy’ roots, and that he has only returned for a brief while.

This nudges us into Sabharwal’s childhood, if only momentarily, and validates his hunger to know more. And I suspect his quest, in form of this passion project, is meant to be more of a stepping-stone in his own personal journey instead of a wholesome viewing experience. Whether we want to join him on this quiet, self-reflecting ride is entirely our choice.

(‘In Their Shoes’ released in select Indian cinemas in March, 2015)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.