Directors: Gajendra Ahire, Viju Mane, Girish Mohite, Ravi Jadhav

Cast: Neena Kulkarni, Suhas Palshikar, Kushal Badrike, Spruha Joshi, Mangesh Desai, Smita Tambe, Veena Jamkar, Mrunmayee Deshpande

Section: Marathi Talkies

Schedule: October 24th, PVR ICON (Audi 1), 4.30 PM — with Q&A

In a velvety voice that could lend grace to even an item song, he sets the foundation; “poems are bubbles in time,” he intones, “They charm and disappear, leaving behind faint moments of artistry.”

Dil-e-Nadaan

That these bubbles abruptly burst at their peak is a fact not lost upon the two ageing protagonists of Gajendra Ahire’s melancholic Dil-e-Nadaan, based on Mirza Galib’s ghazal of the same name. Perhaps the final remnants of a troupe that graced mehfils across the world, a classical singer (Kulkarni) and revered Sarangi player (Palshikar) now sell almonds from their terrace to make a living. There’s still a regal air about them; their chatter is laced with denial, yet a resolute awareness that resists fate and forgotten stature. Greatness is difficult to endure, especially after it passes. Ahire directs his veteran actors as if they’re on stage; allowing viewers to indulge the old couple over three clear acts. This film retains the maximum poetic reverb of the four, unfurling in a single room decorated with glorious memories and instruments from a life gone by.

Ek Hota Kau

The second, Viju Mane’s Ek Hota Kau based on Kishore Kadam’s poem, tells a kinetic and melodramatic tale about a man cursed with dark complexion. Unlike Raanjhanaa, it explores the sweeter side of a one-sided inter-caste romance—complete with a Pandit father and pointed jabs at the boy’s physicality. Kushal Badrike excels in his portrayal of this lowly mechanic. Rain, powder and then white cream are used to make obvious ‘Fair and Lovely’ metaphors, while jittery GoPro shots disrupt the repetition of ugly-crow epiphanies. Despite natural supporting acts, its overwrought treatment reiterates the core importance of retaining simplicity as a stylistic choice.

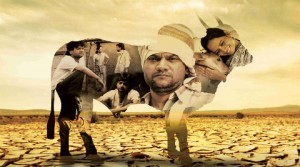

Baiil

The same can’t be said about Girish Mohite’s ‘Baiil’ (bull), based on Lokanath Yashwant’s poem, about an impoverished cotton farmer (Desai; passionate) discovering the harsh truths of urbanization and survival. His condition is deeply relevant in today’s India, but it’s ironically the poem that nutshells his life into a convenient montage of decisions over music. The film is peppered with his desperate monologues, providing a fleeting insight into tragic cause-and-effect lives of rural families. Mohite under-utilizes the narrative device of a lonely Ox mourning his frustrated master; it becomes secondary to the farmer’s theatrical moments of weakness.

Mitraa

The final film, Ravi Jadhav’s ‘Mitraa’ based on Sandeep Khare’s poem and Vijay Tendulkar’s story, is the one that will pop into my mind when I look back at this anthology. Veena Jamkar gives a compelling performance as Sumitra, a lesbian in pre-independence India struggling with feelings for her hostel roommate. “What is the colour of sadness?” ponders her childhood friend lyrically, a boy who has his heart broken by her reality. Jadhav appropriately shoots this in stark shades of black and white around Victorian-era buildings, consciously highlighting her offbeat mannerisms and mental space. He indulges with the narrative, bookending it with surreal imagery and a piano-heavy score, and unleashing characters that introspect aloud. My only grouse is Jadhav’s choice of pubescent flashbacks; it oversimplifies Sumitra’s ‘condition’ into a cliché meant for family audiences.

While these films are largely unrelated, each of them employs mentally fragile characters dealing with defining phases of their environments. At times, the same poems that inspire these films restrict them too, much like many cinematic adaptations. There are many opportunities to break free of the original sources and craft a more endearing package. But much respect is given to the literature — a bit too much, occasionally, as is often the case with Indian filmmakers.

Eventually, much like old-fashioned Bioscope ‘traveling cinema’ shows (incidentally, a charming documentary on this, called ‘The Cinema Travellers,’ which premiered at Cannes this year, is part of the MAMI line-up too), this serves up a variety that goes beyond mainstream genres; it casts a fair umbrella over the different aesthetics and moods of Marathi cinema.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.