By Prasanna Vighne

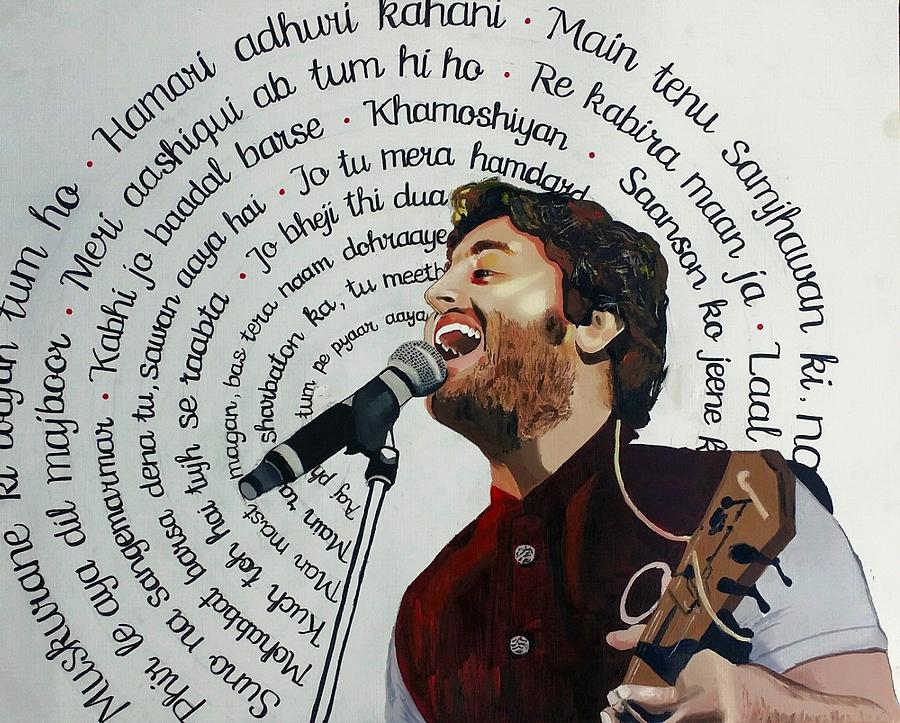

Arijit Singh is an icon. Yes, already.

When I was twelve, I remember reading The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes for the first time. It was an edition that is no longer available, at least on Amazon. It was my first book purchase that wasn’t supervised by my parents – in 2002, at a Scholastic book fair organized by and at our school. The preface of that book was by an author who I sadly don’t remember now. He (it was a ‘he’) defined an Icon as someone whose name is now synonymous to and patented with their persona. Icons could become so recognizable that often don’t even need last names, he wrote. He argued that, like ‘Hitler’, no parent can name their kid ‘Sherlock’ anymore without avoiding the connection to the character and without placing some unfair disadvantage on the kid’s life. Today, I can think of Beyoncé that fits the description. But I remember thinking then, that by that definition, Sachin is not, but Shah Rukh and Amitabh surely are icons. The exclusion of Sachin made me skeptical of the definition, and yet, that’s the definition that appeared in my mind as I started this piece.

Arijit Singh is, by definition, an icon.

For the last ten years, he is ubiquitous in mainstream Hindi music, and yet we, the commonfolk, knew very little of him until this 2018 profile by Sankhayan Ghosh, and more recently, Pagglait. Playback singers are anyway not as accessible as film stars. The mystique that stars today lament is a relic of a bygone era can still be found with and around singers, to a large extent. Even within that group, Singh had managed to maintain a relatively low profile. Most knew him by the consistency with which he seemed to sing all the slow, romantic, sad, balladic, heartbreak melodies Bollywood had to offer. There came a point where Arijit Singh Nausea was a real thing. He had carved his niche, his genre, just like Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, and Atif Aslam, and Kailash Kher had carved theirs before him.

The difference was that Arijit was a “hero” singer, a superstar, whose star never seem to wane, bless him. Unlike them, he was not a trend. He could somehow manage the peaks of his ubiquity, partly because of his apparent good nature and partly because he spoke to a generation that seemed to be breaking their hearts just to wallow in his songs. His kind, droopy eyes weren’t dreamy but they were humble and yearning. His voice wasn’t dipped in honey, like say that of a Sonu Nigam or a Shaan. But his gruff, gravelly, scratchy voice could still melt hearts, thanks to the ache and honesty in it, one that shone through when his voice cracked or when we could hear his breath between words. He didn’t seem to find those “imperfections” something to overcome. While other “hero-male-singers” sang perfectly like they knew every inflection and every turn from a mile away, Singh sang as if he went alongside it and discovered the song as he sang it. He let us discover it with him. Many of his songs sounded like earnest pleas. Like Udit Narayan’s smile did, Arijit’s sincerity underlined and shot through his songs. It made it seem like he wasn’t singing for us, but for his own self. Listening to him croon at concerts felt like watching an ascetic deep in meditation; you wanted to let him be and soak in the peace that he was summoning. When it wasn’t this spiritual, it was still intimate. He seemed like a friend who would sing for you at one of those late-night, alcohol-dabbed jamming sessions or at campfires. Arijit’s conquered his omnipresence with his sincerity.

All this was not without any technical merits. While the masses lapped up his songs, the experts (and the elites) recognized that he was technically accomplished. Shankar Mahadevan, Amitabh Bhattacharya, Amit Trivedi, Sanjay Bhansali, everyone vouches for his mettle. That he is worth the hype and wasn’t just another fad was evident when he was chosen to voice Sadashiv, a classical singer in the Marathi musical drama, Katyar Kaljat Ghusali. He sang a Qawaalli jugalbandi and a bhajan. In the same year (2015), he made his Hindi debut for A.R. Rahman. All that untethered and adventurous singing notwithstanding, A. R. Rahman mentioned in one of his interviews how Singh performed the dual-pitched ‘Agar Tum Saath Ho‘ with such precision that he didn’t have to adjust the two tracks in post-production; each note of one perfectly overlapped the corresponding note of the other. And for all the “sad-Arijit-song” memes, he has sung memorable tunes in almost every genre and can sound different when he needs to. An example would be how he sounds deceptively like Amit Trivedi in the song ‘I am India‘ from 2017’s ‘Qaidi Band‘, an album composed by Trivedi.

In the profile by Zico Ghosh (linked above), Singh predicted his own fall around the year 2018. The year came and went. Arijit is still here. His emphasis on programming, instrumentation, and arrangement was also mentioned in the same article, and his debut album, ‘Pagglait’ is the pudding with its proof for it.

The last few years have seen a consistent grumble, an uproar of sorts, flowing under every conversation about Hindi film music. We mourned the death of quality and originality in Hindi film music, as we seem to do after every few years. As it turns out, while the noise was not unwarranted, the volume of it was. The pandemic years seem to have corrected it, somehow. Sanya Malhotra can herself boast that three of her films saw three of the best albums in recent years, Ludo, Meenakshi Sundareshwar, and, relevant to us here, Pagglait. More than any other, Pagglait made me realize that original and good Hindi film music wasn’t dead. We either needed to look outside Hindi films for it or, in the case of Pagglait, we needed to look at the music as if it belonged to an indie album, like Ritvitz, Prateek Kuhad, or Swarathma. Perhaps that would have given it its dues.

Since I am no expert in music, I can only praise what I understand and explain what it feels like to me.

Like the fact that the album boasts of twenty-four tracks, includes a ton of instrumentals, and was released under his own label, Oriyon Music. In an age where male singers dominate the landscape for songs even for female-led films (Raazi, Panga, Dangal, Manikarnika, Ek Ladki ko Dekha toh Aisa Laga, Badla, Khandani Shafakhana, Zoya Factor, Thappad, Simran, Chappak ), here was an album that featured 80% female voices, including Neeti Mohan, Himani Kapoor, Meghna Mishra, Chinmayi Sripada and Jhumpa Mondal. Singh took a backseat.

The album is penned by Neelesh Mishra, the everyman poet, and storyteller. Mishra’s lines lend the music the heft it needs, given the subject. At the same time, his lyrics aren’t drab. They are uplifting to fit the theme of finding freedom and disagreeing with one’s duty. The words are simple, but not simplistic. At times, serpentine, free-verse poetry with varying meters is complimented by simple rhymes (Taanka Jhanki, Toka Taaki). At times, his lyrics capture the smallest wishes – say that of holding on to a moment, with the tenderness of a straw (Tinka haathon se uda; dil ka bichadna, dil ka milna, ek lamha). Neelesh Mishra even manages to send chills down our spines in the maddening Phire Fakeera with lines like “punar-janm ki rasm karenge, rooh apni bhasm karenge.” My favorite line is “Hoton ke mundero, pe chipi hai dhero choti choti si khushi.” As unpredictable and unique as Arijit’s music is, Mishra’s lyrics match it with equal amounts of warmth and confidence. They seem ready-made for it in fact, like how Gulzar’s words for ‘Dil Se‘ feel like they are made for Rahman’s music.

As for the music itself, even if I didn’t know that Rahman and Pritam are his gurus or mentors, the music would give it away. That’s not to say that Singh does not innovate or put his own twist on it. In fact, he puts the story at the forefront is obvious, from the music and from this interview. The songs put Sandhya’s emotions at the forefront, from confusion to acceptance to freedom; and the songs with their multiple versions are apt for these moods even though all versions aren’t utilized in the film. The multiple versions also give Singh a chance to experiment and show his grasp of arrangement. Each version works on its own merits and adds something unique to the same lyrics. My favorite song is “Radha’s Poem” by Chinmayi Sripada, a version of “Thode Kam Ajnabi“, my favorite song of the 2021.

One sentence reviews of each song:

- Dil Udd Jaa Re sounds like it belongs to a time spent sitting at the window of a moving train.

- Lamha sounds like a stroll taken along the Siene in Paris on a winter evening with a lover.

- Thode Kam Ajnabi sounds like a smile that cracks through our tears when a friend makes us laugh despite ourselves.

- Phire Faqeera (with it’s background chant of “pagal, pagal…”) feels like being trapped inside someone dancing in a halllucinogenic trance.

- Pagglait sounds like a montage of our most fun and memorable moments spent with crazy friends in college.

Of course, along with Arijit Singh, full credit to Umesh Bist and Neelesh Mishra for making music that gets the balance right, of servicing the film and still being independent.

But more than that, I credit them for introducing us to another layer of Arijit Singh’s talent. With this power unlocked, Singh is little less of a stranger now. And though thoda sa kam ajnabi, he still remains iconic as ever.

(Read more of the author on his blog here)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.