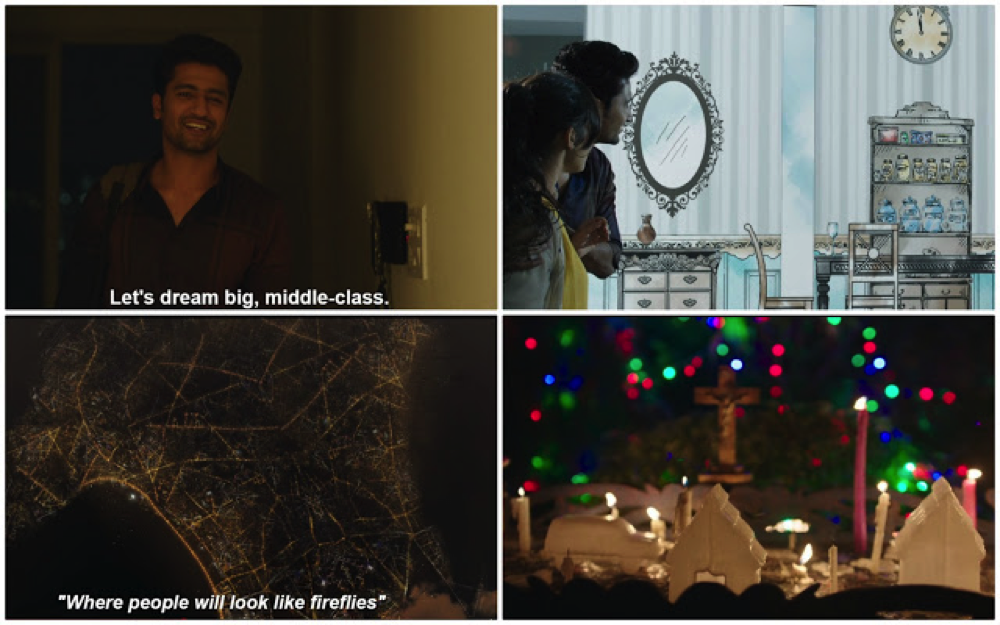

Anand Tiwari’s Love Per Square Foot is the story of Karina D’Souza (Angira Dhar) and Sanjay Chaturvedi (Vicky Kaushal), who dream of owning a house in the city of Mumbai. Both of them work in the same bank. A government housing scheme for married couples is released, and they enter into a deal to apply for it. However, as it often happens, they also fall for each other. The film, then, tries to depict how the two of them overcome the challenges to fulfill their dream of having a home. Love Per Square Foot is India’s first direct-to-digital film and was released directly on Netflix.

Love Per Square Foot, as the title also suggests, is about space. In the opening few moments, Sanjay, sitting on a toilet seat, tells his mother that he needs space. Staying all his life in a railway quarter with his parents, he gets his space to do whatever he wants in the few moments in the toilet. At a later point, Karina tells Sam (Kunaal Roy Kapur) that she needs her own space, and she cannot live with his parents. When Sanjay and Karina are traveling in a local train, they see a couple canoodling in the train. Sanjay remarks that there is no space for couples to even kiss in the city. Much to the surprise of everyone around them, he kisses Karina in public in the train compartment. This lack of space is, perhaps, more prominent in Mumbai, but is not restricted to that city only. If one has traveled in the Delhi Metro, one must have seen couples meeting on the station platforms. Every few months, there are reports in the media of police raiding hotels, and charging people for engagement in illicit activities. This issue is also prevalent in small-town India, as was seen in Masaan (Vicky Kaushal’s first film). Devi (Richa Chadda) and her boyfriend pretend to be a married couple and check in a hotel. However, the hotel is raided by the police and the two are caught in the act. There is a similar moment in Love Per Square Foot, too, where Sanjay and Karina go to a hotel for some private time with each other, but the caretaker tells them to run away as there has been a police raid on the hotel premises. This lack of space is one of the most underrated challenges in a predominantly conservative country, having the largest population of youth in the world. This is why it is heartening to see startups, such as StayUncle, doing some amazing work to provide a solution to this.

The space that Karina and Sanjay talk about is not just physical, but, it is also emotional. The dream house is not only a means to have a physical space of their own, but it is also about having a chance to live life independently and to take your own decisions. When Sanjay is trying to convince Karina to fill the application form, he tells her, “Tumhara apna ghar hoga na, Karina, toh phir tumhe apni zindagi apne terms pe jeene se koi nahi rok sakta.” If she has a house of her own, no one can stop her from living her life on her own terms. After they apply for the house, Karina tells Sanjay that she cannot pay the security deposit as her mother controls all her finances. Her mother was making all the decisions for her, from her finances to the choice of her husband. When Sanjay tells his parents that he got a house, his mother’s attitude towards him changes. Earlier, she was always on the side of her husband; however, she supports Sanjay now, prompting her husband to tell her to not change sides. It is as if having a house gave both of them some power and freedom to their life. Thus, the space that is shown in the film is both external and internal. In a blink-and-miss moment, when Sanjay and Karina go to apply for the house, the names of the couple in front of them are depicted as Reza and Lata. We don’t know their story, but it is clear that they belong to different religions. Maybe, they are applying for a house of their own to break away from their families and live a life together.

Sanjay and Karina hardly got any space, and, thus, we see their most private moments happening in public. They make their decision to apply for a house in an auto rickshaw. They make out in trains and auto rickshaws. When Karina comes to talk to Sanjay, she asks him if they can sneak into his room. He replies that he does not have a room of his own, and he sleeps in the hall. They, then, go to the terrace to talk. When they kiss there, the residents of the other building tease them. Sanjay remarks that Karina must appreciate his timing as he proposed to her in a rickshaw and now he is saying to her that he loves her through a television. At another stage, when Sanjay is going to his wedding, he is forced to change his clothes in public. Finally, in the end, when they get to talk to each other, they are again surrounded by their relatives, but they are standing at some distance from them. The relatives cannot fully understand the talk between the couple. Sanjay and Karina, somehow, always managed to get their tiny spaces to have private moments in public.

There is a point in the film where Sam takes Karina to his house and offers her a room where she can stay with her mother until the time they get married. The windows of the room have grills. They don’t open because they are jammed. Sam tells her there is no need for the windows as there is an air conditioner to compensate for the lack of fresh air. This ‘space’ that Sam offers Karina is almost a reflection of their own relationship—artificial, fake, and claustrophobic. Karina is not truly free and feels suffocated in their relationship. She is trapped in its superficiality. It is only a compromise for a house. Karina desires a relationship where she and her partner contribute ‘fifty-fifty‘ to everything. However, her relationship with Sam is the one where only he contributes. Karina wants to be an equal contributor to the relationship, and that is why she does not feel happy with all the amenities that Sam offers her, even if she really needs those amenities. Sam is the more dominating decision-making partner, and treats their relationship no different than the one between a master and a servant. He gives money to his driver to apply for the same housing scheme that Karina wants to apply as well. In the same scene, Sam gets irritated when his servant does not come at once when he pressed the buzzer. For him, Karina’s wishes are no different from the people who work for him.

In fact, this domination is seen in Sanjay’s boss Rashi (Alankrita Sahai) and her fake relationship with Sanjay as well. Rashi’s employees always wonder as to why she treats them like slaves. Rashi calls Sanjay as her slave, and he, in turn, calls her boss. Even though they might be role-playing in such conversations, it provides pointers to the nature of their relationship. In the initial moments of the film, Rashi warns two employees that she will fire them if they do not present her a plan B. When her boyfriend Kashin (Arunoday Singh) comes back, she tells Sanjay that he was her plan B. She is only looking for a safety net. Sam and Rashi think about their self first (nothing wrong with that), while Karina and Sanjay desire an equal relationship.

In Hindi cinema, there have been numerous instances where there has been a distinction made between a makaan (house) and a ghar (home). A makaan implies the physical aspect of the building, while a ghar refers to the people and the feeling associated with the place. In Naseeb (1997), a character says, “Bhare saawan mein reghistaan lagta hai, yeh ghar mera khali makaan lagta hai.” In Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, Anjali’s mother tells her, “Woh ghar jo samjhaute ke balboote par bana ho, pyaar nahi, woh ghar nahi, makaan hota hai.” A house made on a compromise and not love is a house and not a home. Here, again, the film makes a distinction between a ghar and a makaan. In the early moments of the film, Sanjay’s mother Lata (Supriya Pathak) tells him, “Ghar moti deewaron aur kamron ke size se nahi banta. Jo log andar rehte hain na usse banta hai.” Home is made up of the people who live in it, and not by the size of its walls or its rooms. He dismisses it by saying that there are already too many people in the house. When Sanjay realizes the importance of a home, he tells Karina, “Main ghar nahi, makaan chah raha tha.” It is this realization that the film tries to underscore that the foundation of a good home comprises a house and the people associated with it.

My favorite song in the film, Aashiyana, depicts some splendid moments. The song is primarily shot in and around an apartment building. After all, it is the dream of Sanjay and Karina, and it is only fitting that they go to their dreamland in such a song. They are completely at bliss in this song. There is a particular sequence where they see a shot of Mumbai from the night sky, and the lyrics say, “Hon door itne, us zameen se, yun lagey aise. Haan! Jugnuon se, jaltey bhujtey, log ho jaise.” We will be so far away from the land, where people will look like fireflies. It is, again, reflecting their desire for space, far away from the other people. It is almost like they are sitting in their own heaven and can see everyone from the top. There is also a tribute to Gulzar the lyrics. Baarishen khul ke, jab bhi ghar humare aaye, gaane Gulzar ke, mil ke gungunaien. Whenever the rains will come uninvited, we will sing a song by Gulzar.

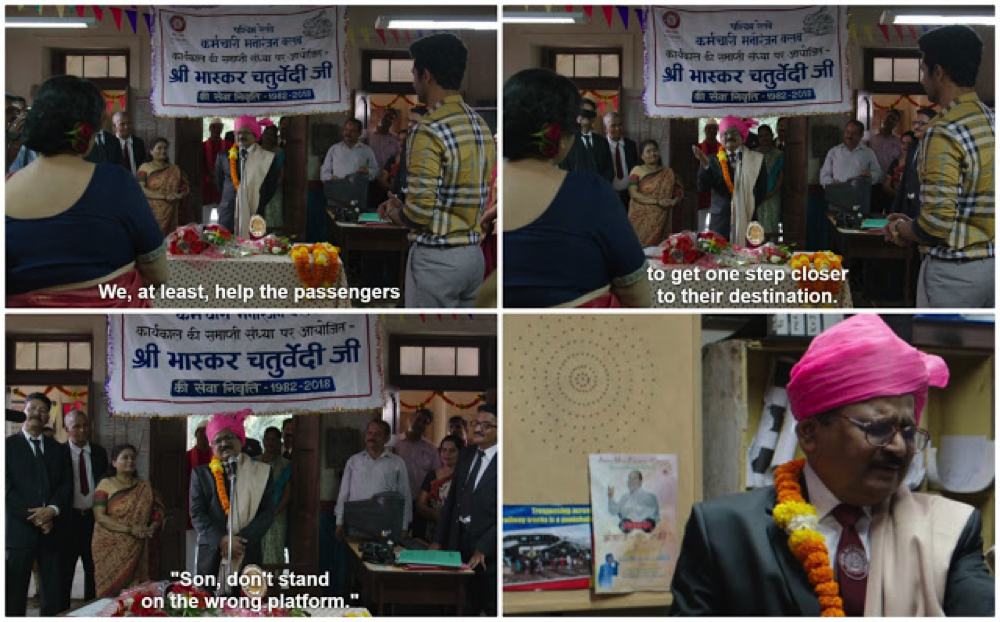

The film’s other Gulzar moment comes in the best scene of the film. Bhaskar Chaturvedi (Raghubir Yadav), Sanjay’s father, gives his retirement speech. He says that he has been watching the railway tracks for the past thirty years. These tracks are like the lines of a hand that never fade away. He had wanted to be a singer, but could not make it, so he became a railway announcer. He has no regrets (he uses the beautiful word malaal for regrets) because, in a way, he helped people reach one-step closer to their destination. If he had not done this job, many people will lose their trains. All the travelers are like his children and he has only one advice for them, which is to not stand on the wrong platform, else they will be left stranded forever. Then, he goes on to sing, Musafir Hoon Yaaron from Gulzar’s Parichay (a picture of Mohammad Rafi can also be seen behind). It is a poignant moment where a man who spent thirty years in a job gets to say one final goodbye in his unique way.

At an early point, Blossom (Ratna Pathak Shah), Karina’s mother, in a moment of fury, tells her that she sacrificed her life for her, and Karina will never be her. “You will never be me.” Later, when she is getting married, she again brings up the conversation and says that Karina should not become her. “You shouldn’t become me.” Blossom has been staying in someone else’s house, and living on her brother’s charity. Karina, however, will stay in her own house with a man she loves, and lead a life by her own terms. She will not be like her mother. I felt there is a similarity in the two sets of parents in the film. Sanjay’s parents live in a house given by the Railways, while Karina’s mother stays in a house of her brother. Their houses are literally crumbling. Sanjay remarks that when he tries to put a nail in the house, the entire house shakes. The walls of Blossom’s house are collapsing bit by bit every day. Chalk keeps falling on their heads. Even the professions of the parents depict old-school nostalgia. Bhaskar is a railway announcer, while Blossom is a seamstress, who still uses a sewing machine. With the advent of rapid automation, such professions would cease to exist in another twenty years. Additionally, in today’s generation, it will be rare to find someone who works at the same place for thirty years. Our parents’ generation will be the last of these people. Like the crumbling houses, an old world and an antecedent thought-process are slowly being replaced by new ones. You will never be me. We will not be like our parents. I could not help but think of Bunty Aur Babli, one of the earliest films that depicted this generational change much before it became common. Rakesh (Abhishek Bachchan) fights with his father, who wants him to follow his path of becoming a ticket-checker in the Railways, while Rakesh has bigger plans for himself. The bylanes of Fursatganj are not his destiny. The always-so-brilliant Jai Arjun Singh explains this change much better here.

There is definitely a vibe of the web series Bang Baaja Baraat and Permanent Roommates in the film, as the writers of this film, Anand Tiwari and Sumeet Vyas, have been closely associated with those shows, respectively. Also, the auto rickshaws in the film have a character of their own. I kept looking forward to the rickshaw scenes to see what reference will be shown in them. One depicted Raj and Simran from Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge with the mandolin; another one had Sahib Jaan from Pakeezah; another one had a bride and a groom that appears at the time when Sanjay and Karina were also thinking to get married. Going solely by the song Yatri Kripaya Dhyaan De, Zoya Akhtar’s Gully Boy, a film on Mumbai’s street rappers, seems something to look forward to next year. Finally, many commentators have observed the parallels between Love Per Square Foot and Bhimsen Khurana’s Gharaonda (written by Gulzar; another Gulzar tribute).

In the recently released Economic Survey 2017-18, there is an interesting section devoted to housing in India. It states that the share of rental housing as a percentage of total households in India has been declining in Indian cities since independence. Rental housing decreased from 54 percent in 1961 to reach 28 percent in 2011. Owning a house is a dream for many, and the data corroborates that people want to have a home of their own. Despite the shortage of housing in urban India, there is also a trend of increase in vacant houses. Surprisingly, Mumbai has the highest number of vacant houses in the country. No one knows for sure why it is like that. But, in a city, where there is a clamor for every inch of space, owning a house is indeed a luxury. Just having a toilet in a house is its own privilege in the city (looking at you, Mrs. (Un)Funny Bones). Maybe that is why Love Per Square Foot opens and ends with men wearing a cape. Owning a house, especially in Mumbai, requires every person to bring out their version of Superman. And, the rest of us can dream, and hope that our dreams come true on their own.

[Read more of the author’s work on his blog here]

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.