The great Sigmund Freud, considered to be the father of modern psychology, had proposed a highly controversial theory called the Oedipus complex (also called Oedipal). Although he had mentioned this theory in his book The Interpretation of Dreams and in his other early works, he completely articulated his ideas about the Oedipus complex in a case study. In 1909, Freud wrote a paper Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-Year-Old Boy, where he tried to understand the fear of horses of a boy named Little Hans. He believed the boy’s terror was due to feelings of anger for his parents that he had internalized. Freud’s theory states that all small boys select their mother as their primary object of desire. They subconsciously wish to usurp their father and become their mother’s lover. The child suspects that acting on these feelings would lead to danger, therefore, his desires are repressed, which leads to anxiety. He called it the Oedipal complex, named after the Greek tragedy play Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, which is the story of the king Oedipus, who murders his father and marries his mother. Carl Jung had postulated a female equivalent, known as the Electra complex; however, the term never caught on, and Oedipus complex is now largely used to denote the relationship between three parties (one child and two parents) where the child competes with one parent for the love and affection of the other. Although Freud believed the complex in a sexual way, over the years, some have considered that the relationship doesn’t need to be sexual to be considered Oedipal, and includes any inter-generational conflict.

Indian psychologists have also hypothesized a different version of the Oedipus complex called as the Indian Oedipus complex. In this model, instead of sons desiring mothers and overcoming fathers, and daughters loving fathers and hating mothers, most often, we have fathers (or father-figures) suppressing their sons and desiring their daughters, and mothers desiring their sons and ill-treating their daughters. The structure is same as that of the Freudian model but the relationship of desire is reverse in the Indian model.

There have been a few Hindi films that have explored the Oedipal complex, but by and large, the controversial theory is present as an understated subtext with non-sexual tones. One of the recurring themes in Hindi cinema has been the role of mother-son relationships, but not many films have dared to cross the boundary. The familial relationships are treated reverentially, and any deviation is frowned upon in the conservative Indian society. However, it is still an interesting exercise to explore where themes related to Oedipal complex are present in Hindi cinema.

One of the earliest films where there was an Oedipal context is Mother India (1957). Directed by Mehboob Khan, the film is the story of a poverty-stricken village woman named Radha who, in the absence of her husband, struggles to raise her two sons Ram and Birju. She has to also learn to survive against a usurious moneylender. In the film, there are clear signs of Oedipal feelings between Radha and her son Birju. In National Identity In Indian Popular Cinema, 1947-1987, Sumita S. Chakravarty writes, “Birju who takes gambling, thieving, and ultimately to highway robbery, is actually indulging in a form of self-aggression, to protest what he sees as the withdrawal of his mother’s affections. His nostalgia for her softer and nurturing side, as also his Oedipal longings, is expressed by his obsessive attachment to her bracelets. The film sublimates Birju’s incestuous longings for the mother by presenting the motivations for Birju’s actions as anger that his mother’s bracelets have been pawned to the moneylender.” In Filming the Gods: Religion and Indian Cinema, Rachel Dwyer notes that Radha’s husband was named Shyam (a name for Krishna), and her rebellious son was named Birju (another name for Krishna) which also could be read as a symbol of an Oedipal relation. It was also the case that the actors playing Radha and Birju actually got married in real life.

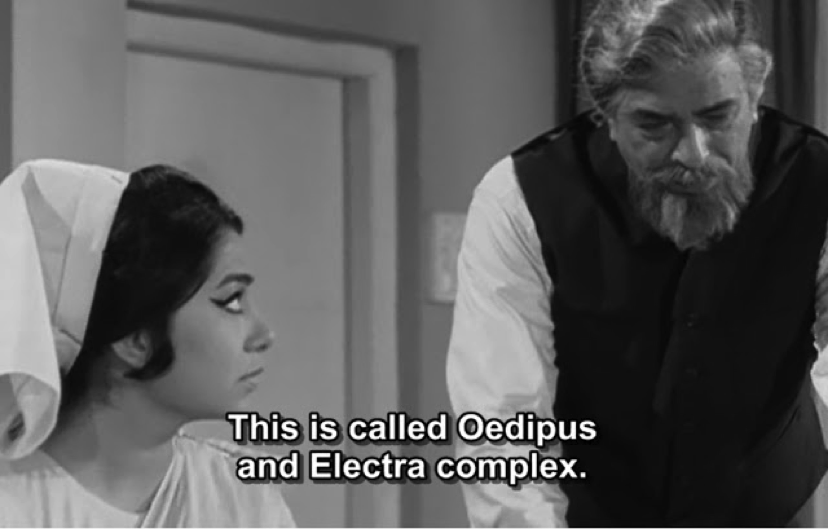

In Khamoshi (1969), there is actually a description of the Oedipal complex, perhaps, the first Hindi film to mention it. Directed by Asit Sen, Khamoshi is the story of a nurse Radha who works in the psychiatry ward in a hospital. She is asked to take care of Arun, a writer who lost his mind after his lover rejected him. Radha starts taking care of him and, eventually, falls in love with him. In the early moments of the film, Colonel Saab, the head doctor, explains the treatment for Arun, and he talks about the Oedipal complex. He says that in childhood, when a man opens his eyes, he moves around and becomes familiar with his surroundings. This is called the auto-erratic state. After that, he looks at himself in the mirror and feels happy and for the first time, he falls in love with himself. This is called the narcissist state. After this, he learns to love his mother or father; if it’s a girl then her father and if it’s a guy then his mother. This is called the Oedipus or the Electra complex. When he realizes that it is not acceptable to love one’s mother then he reluctantly removes her from this place and looks for this kind of faith for the face, of this motherly affection. He, then, adds that the nurse will have to play a role so that Arun finds that his mother and his lover’s face is the same. This is called establishing the rapport with the patient, which will help him in being treated. Radha, after some reluctance, agrees to treat Arun. At some point in the film, the mother of Radha’s ex-lover Dev, who was also treated by Radha using the same treatment, invites Radha to her place. Dev’s mother tells her that she might have given him birth, but it was Radha who gave her another life, again, highlighting the Oedipal theme in the film. In his book Mad Tales from Bollywood: Portrayal of Mental Illness in Conventional Hindi Cinema, Dinesh Bhugra writes, “That Radha, as a nurse and a therapist, is a representation of the sacrificing mother, who has nurtured her sons in an erotic-nurturant manner in the Indian Oedipal complex style is clear.”

In the 1970s, Javed Akhtar and Salim Khan wrote many scripts that had Oedipal overtones. Directed by Yash Chopra, Deewar (1975) is the story of a mother and her two sons. One of them becomes a policeman, and the other becomes a criminal. The two sons, Ravi and Vijay, follow different principles in life. At one point, the two of them compare their assets, and Ravi wins simply because he has their mother with him—Mere paas maa hai. There are Oedipal feelings in both Ravi and Vijay. In the end, Vijay dies with his head in his mother’s lap. The mother had chosen Ravi over Vijay, and she is the one who hands the gun to Ravi to kill Vijay; however, in Vijay’s last moments, he remembers the time when he used to sleep in his mother’s arms. He says he never slept since he separated from her. This is a deeply Oedipal moment. At some other point, Vijay risks his life to meet his mother at the promised place. It is also worth noting that the film’s English title was called I’ll Die For Mama. In Cinema As Family Romance, Priya Joshi writes, “In this, Deewar presents a notably authoritarian—and eventually unstable—version of the Oedipal drama in which neither generation ultimately prevails. Both father and child are demolished, and power resides in absolutist fashion with a ruthless central authority that is unwilling to cede or share it.” In another Oedipal reading from Ravi’s viewpoint, he is the one who gets to keep his mother with him, and it is he who informs his mother of her husband’s demise. He is also the one who kills her other son whom she loves, eliminating all competition, thus, demonstrating the Oedipal complex.

In Trishul (1978), which was also directed by Yash Chopra and written by Salim-Javed, the story revolves around a son Vijay who is born out of wedlock. His mother Shanti was in love with Raj Kumar who ditched her and married a rich girl as wished by his mother. Shanti leaves the town but is pregnant. She raises the child on her own. On her deathbed, she reminds her son Vijay of her father’s abandonment and asks her son to never forget her life. Vijay comes to Delhi and plots the destruction of his father’s business. Unlike Deewar, where the Oedipal conflict was complicated by the absence of a father, the conflict in Trishul is conventional where the child takes revenge for her mother by killing his father. In Encyclopedia of Hindi Cinema, Maithili Rao calls Trishul ‘the most overtly Oedipal film in mainstream cinema, where the illegitimate son not only ruins his father’s business but also alienates his legitimate children from him.’ Salim-Javed wrote yet another film Shakti (1982), directed by Ramesh Sippy, that portrayed another version of the Oedipal conflict. The film revolves around yet another character named Vijay, and his animosity towards his police-officer father who was willing to let his own son die when he was kidnapped.

In the 1990s, Yash Chopra made Lamhe (1991) that became one of the first films that portrayed an Electra complex (Oedipal complex from a female point of view). Lamhe is the story of Viren Pratap Singh, a prince belonging to Marwar, He falls in love with the girl next door, Pallavi. She is elder to him in age though this does not bother him. Pallavi loves someone else and gets married to him. Unable to bear his heartbreak, Viren goes to London. Meanwhile, Pallavi dies in an accident and leaves behind a daughter Pooja, under the care of Viren’s Daijaan. Viren does not see Pooja till she becomes an adult; however, she grows up to become an exact replica of her mother. This time, Pooja falls in love with Viren, who is obviously much elder to him. Viren has to decide whether he is still in love with Pallavi, or he is deliberately trying to stop himself from falling in love with Pooja. Viren and Pooja might not be related by blood, but Viren is a fatherly-figure to Pooja, fitting the definition of the Electra complex. The film was a box office failure and was called too far ahead of its time. Perhaps, one of the reasons it did not work was the audience could not accept that Pooja as a daughter falling in love with a much older fatherly-figure man. Their relationship would become sexual after their wedding, and as such, it could be debated if their relationship was incestuous or not (personally, I love the film).

Many commentators called Lamhe to be an example of Indian Oedipal complex, a different version of the Freudian model. The Indian model has been seen in a few other films, too. In Rakesh Roshan’s Karan Arjun (1995), a revengeful mother’s desire for her two sons is so strong that they take another birth to meet her. In a particular song sequence, the two sons and their mother sing Yeh Bandhan Toh Pyaar Kai Bandhan. Shot in the mustard field, they sing about how their relationship will last ages, a concept usually reserved for lovers. Inspired by the novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Priyadarshan made Kyon Ki (2005). The film is the story of a mental patient Anand who is kept in a mental hospital, as he lost his sanity after he accidentally kills the girl he loves. In the asylum, there is Dr. Tanvi who falls in love with Anand. When Tanvi’s father Dr. Khurana finds out that she likes Anand, he is enraged. In Eavesdropping: The Psychotherapist in Film and Television, Dinesh Bhugra and Gurvinder Kalra write that this is another symptom of the Indian Oedipal/Electra complex. They write, “When Dr. Khurana realizes that Tanvi is in love with Anand, he cannot bear it because he has given all his love to her, and cannot conceive of her leaving him. This is one reflection of the Indian Oedipal complex, where a relationship between father and daughter is close, and the father is not prepared to deal with competition.” There were similar instances in Shoojit Sircar’s Piku (2015) where a perennially-constipated father Bhashkor Banerjee wants his daughter Piku to stay with him forever. He does not want her to get married, and he scares away Piku’s potential suitors by telling them that she is not a virgin.

In Imtiaz Ali’s Highway (2014), a Delhi girl Veera is kidnapped by a group of men, and taken for a ride all over the country. During her journey, she tastes freedom in her entrapment and falls in love with one of the kidnappers Mahabir. At many stages in the film, Mahabir is shown reminiscing about his mother. When he was a kid, he used to hate the way his father treated his mother. He remembers the lullaby his mother used to sing for him, and he cannot help but cry when he hears Veera singing the same lullaby. At one stage, she pats his head like his mother used to do. In the end, when they reach Kashmir, Veera almost becomes his mother. When they find a small hut, she tells him to not come inside the house till she cleans it. She cooks for him. Seeing all this, Mahabir cannot hold himself, and cries, “Amma.” Veera consoles him like a child. Like in Khamoshi, the hero sees his mother in the woman he is falling in love with, underscoring the Oedipal elements in the film.

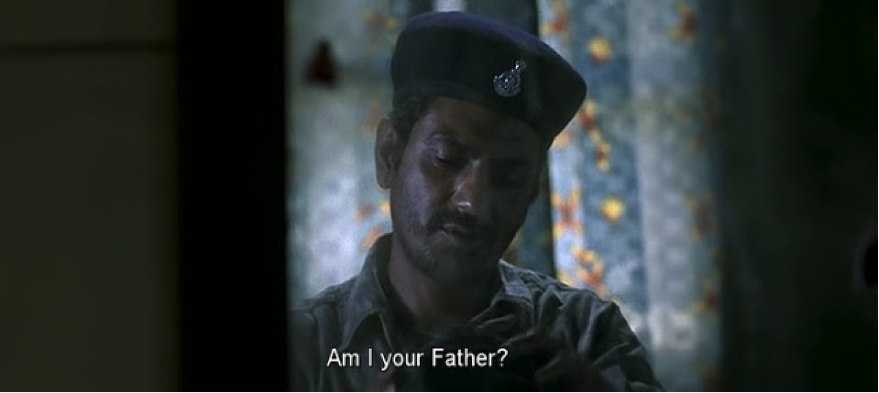

Vishal Bharadwaj made Haider (2014), inspired by Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Based in politically-charged Kashmir, Haider narrates the story of a Kashmiri boy Haider, who finds out that his mother was having an affair with his uncle who might have been behind the murder of his father. In Hamlet, Hamlet had subconsciously desired to kill his father and marry his mother. Similarly, in Haider, Haider’s mother Gazala tells him that when he was a child he used to say that he wanted to marry her. He used to sleep between her mother and her father so that her father could not touch her. Haider, also, perhaps, is the first movie that portrayed sexual undertones between the mother and the son. In a brilliant scene, when Gazala is getting ready for her wedding to Khurram, Haider comes and kisses her neck. In the final moments of the film, Gazala kisses Haider on his lips. In an interview, Vishal Bharadwaj said that he tried to explore the Oedipal complex as much he could within the constraints of the society. He said, “I have explored whatever can be within the parameters of our society. The moment you know about the [Oedipal] feeling, the feeling goes away. It is a complex as long as you are not aware of it.” Like Haider’s relationship with his mother Gazala, there was something special about the relationship between the police offer Parvez and his daughter Arshia. At one point, when Parvez gets to know Arshia delivered Roohdar’s message to Haider, he cooks food for her and puts it in her mouth with his own fingers. There was some chilling quality about that scene as if he was trying to entice her and threaten her into submission to divulge information about Haider. His act of giving food to his daughter after licking his own fingers pointed to some kind of Electra complex. The film touched upon both the Oedipal and the Electra complex.

Heartless (2014), starring Adhyayan Suman, is a medical thriller film directed by Shekhar Suman. In the film, Adhyayan plays Aditya, who requires a heart transplant. He is caught in a mix of deceit and lies by his girlfriend and his doctor who want to kill him to make money from his insurance. Aditya’s mother Gayatri sacrifices herself and commits suicide so that her heart can be used by another doctor to save Aditya. In the film’s final moments, there are touches of an Oedipal complex between Aditya and his mother, like it was in Haider. In a scene where the two of them are out of the conscious real world, they talk to each other where the Oedipal touches are quite discernible.

Ajay Devgn’s Shivaay (2016) is about a mountaineer Shivaay who takes his daughter to Bulgaria so that she can meet her mother. One of the supporting characters in the film is Anushka, an officer at the Indian embassy in Bulgaria. During the song Tera Naal Ishqa in the film, Anushka is in a strange dream sequence in a bathtub. She sees her father in his youth; she goes on to hug him, and the image turns into that of Shivaay. At some point, she also tells Shivaay that women who have good fathers find it difficult to find love. There was a similar setting in Shlok Sharma’s Haraamkhor (2017). The film is the story of an illicit relationship between a teacher Shyam and his student Sandhya. In one of the film’s scenes, Shyam is massaging Sandhya’s head in front of the mirror. Sandhya chides him that he is not doing it the way her father does. At that point, Shyam is also wearing the cap of her father. It is never clear in the film if the lack of fatherly attention was one of the reasons that drove Sandhya to have a relationship with an older man. However, like it is in Shivaay, the film hints that the woman sees the father in her lover in Haraamkhor.

The Oedipal complex has been touched upon in a few Indian regional films as well. Films, such as Devi (1960), Ranganayaki (1981), Vimukhti (2008), Gandu (2010), and Elektra (2010) have explored this complex. The above instances are in no way an exhaustive source but provide few instances where the complex is present.

In Karan Johar’s Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998), there is a scene in the film where an eight-year-old Anjali inadvertently tells her father Rahul that she cannot do everything for him as she is not his wife. In another scene, in the same film, when Tina’s father finds out she is in love with Rahul, he tells her that even if it was someone other than Rahul, he would have felt bad. Since she is in love with another man, her love will get divided. These are pretty harmless dialogues, and nowhere does the film suggest any kind of Oedipal complex. But, somehow, this film came to my mind while exploring this topic. It will be interesting to see if a mainstream film, such as Lamhe, would work today, given that it was called ‘ahead of its time’, and now more than two decades have passed since its release. Indian society is largely conservative in familial aspects, and parents are often compared to godly figures. Any deviation is frowned upon. However, the fascinating thing is that one of the most common words for abuse in India suggests sexual relationships between a son and a mother. Its use is so pervasive, and somehow, we frown upon the Oedipal complex. Sigmund Freud must be smiling from heaven or, perhaps, hell.

[Read more of the author’s work on his blog here]

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.