Director: Anup Kurian

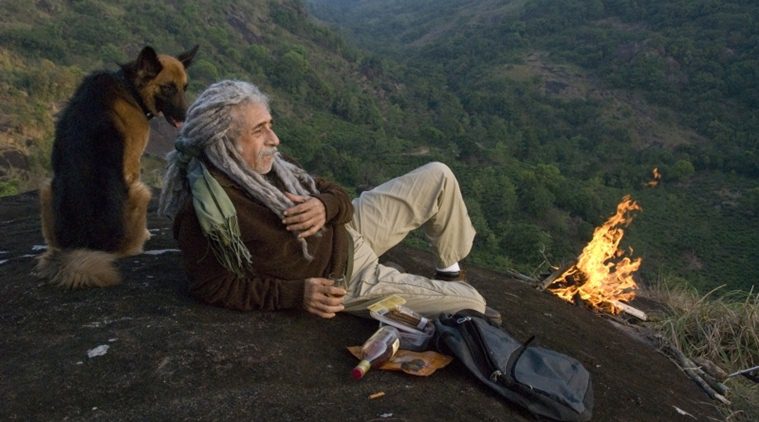

To be honest, I could spend hours watching a man and his dog. The purest form of companionship, a bond too unconditional to be defined. So once I was thrown into the languid world of Colonel (Naseeruddin Shah) and his very affable German Shepherd Kuttapan (yes, a wry name that can only be coined by a reluctant embracer of South Indian culture), I simply followed them around the man’s massive estate.

Colonel and his canine go way back; you can sense it from the way they occupy each other’s spaces. Kutappan spends his evenings immersed in Bugs Bunny cartoons on television, while Colonel spends his days digging ominous graves for potential trespassers. No if, no but, only shoot.

The dreadlocked quasi-rastafarian recluse is also a distrustful sociopath. You would be one, too, if you secretly grew priceless marijuana in your fields and lorded over its trades. This time, though, he wants to retire after his beloved high-potency Blueberry Skunk plants get ready for harvest. It’s a work of art, as most stoners would concur, but this will be his final masterpiece. He’s old, and he’s tired, and he wants to go to Mumbai for a rather romantic (or tragic) reason.

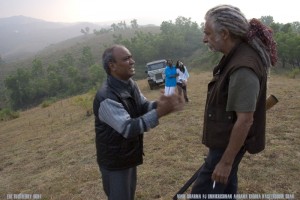

Loneliness is a funny thing though. The most interesting cinema often stems from the most solitary and dour personas. Therefore, when Colonel finds himself in a sticky situation because of a shady client (Vipin Sharma), he is oddly drawn to the promise of ambiguous (human) company.

A flimsy occurrence forces him to take custody of a spunky young girl named Jaya (Aahana Kumra; has some Anushka Sharma in her) for a few days. I wouldn’t exactly classify this as the quintessential Stockholm-syndrome scenario, because he really isn’t the kidnapper. Expectedly, the girl – here because of the elite status of her estranged father – develops this missing bond with the grumpy Indian Rastafarian. This looks plausible, thanks to Shah’s cultivated understanding of how to behave and read the panicked mind of a frightened girl.

Director Anup Kurian isn’t a man of lofty storylines and plots. He lets his characters take shape in front of us, often in real time, to help us live with them. I did begin to emotionally invest in Colonel once I watched him wolf up the delicious beef curry cooked by Jaya. He probably knows it’s a trap to win over his trust, but his temperament – and eager recognition of this one act of selflessness – goes a long way in telling us that he is wounded and humane. We’re left guessing about his past mistakes and deluded dreams. But we do know that Kutappan, his best and only friend till Jaya comes along, is real.

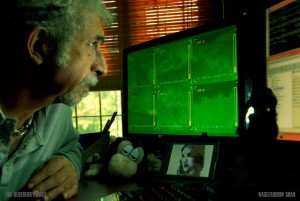

I like the way Kurian uses Colonel’s surveillance room and infrared cameras as devices of constant paranoia. Even I began to get a bit antsy whenever a hazy orangey figure appeared on those beeping screens.

This must have been one of Shah’s most physical roles, what with the grave-digging and running and jumping around. Perhaps all those plants and its medicinal effects may have helped in the long run.

The biggest drawback of Kurian’s meditative portrait is the fact that it is a film. It plays out like a straight line without a beginning or an end – until the traditional contrivances of storytelling are forced upon this universe. Cinematic companions are never allowed to just exist; there are always villainous forces lurking in the periphery (Koyla, Kites, Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai) waiting to strike just as the protagonists start smiling.

Maybe it was inevitable. It could have done without random sharpshooters attacking at the drop of peace. Or maybe I didn’t want to be yanked away from Kutappan and his Colonel, from Jaya and her increasing ease. Sometimes, I do wonder if narrative rules work uniformly across all genres. Kurian could have taken us elsewhere, or not taken us anywhere. After all, rules are made to be broken.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.