Director: Devashish Makhija

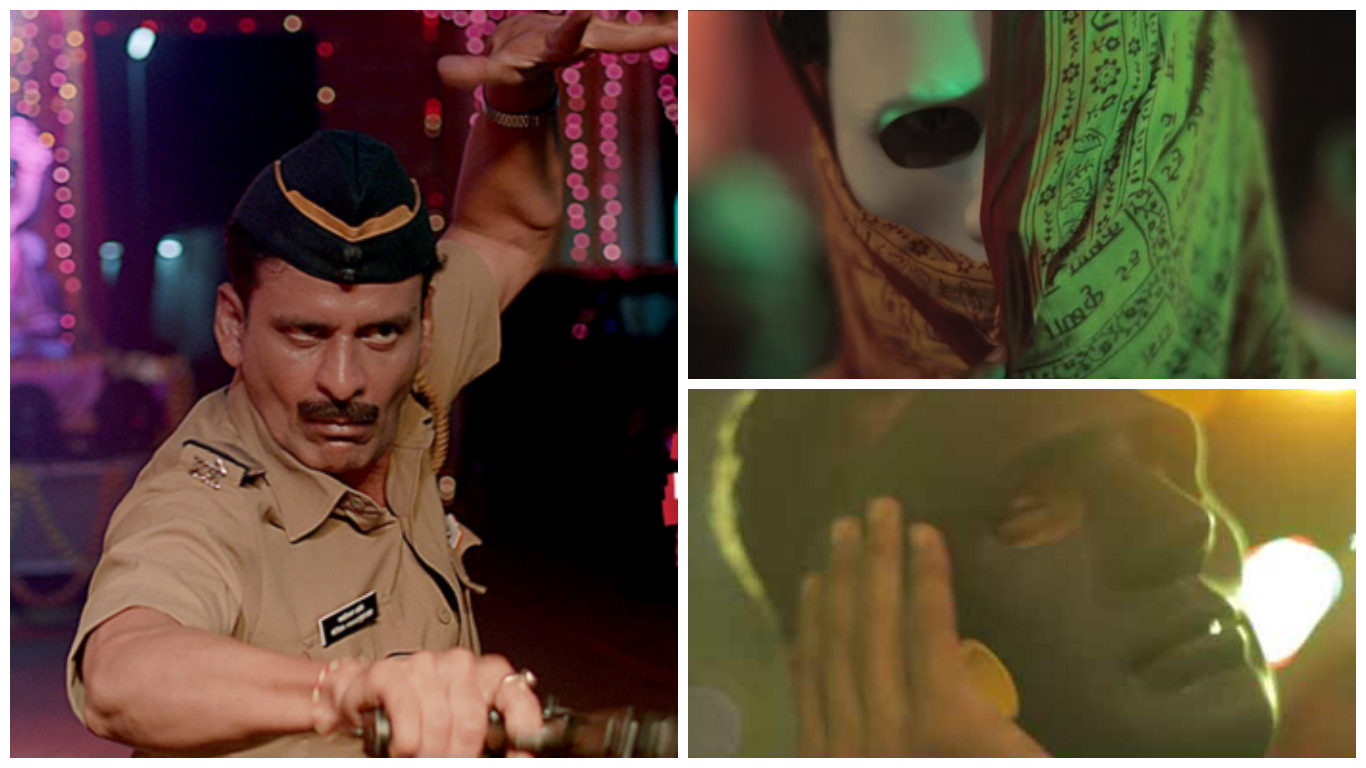

Head constable Tambe (Manoj Bajpayee) is a ticking time bomb.

One senses that he is already mentally stuck somewhere between the idealistic, disillusioned Sunil Kadam (Vijay Maurya) and the cynical, weathered Tukaram Patil (Paresh Rawal) from Nishikanth Kamath’s Mumbai Meri Jaan – two of the most relevant cinematic embodiments of the Mumbai Police Force’s bottom-most tire.

You hope he won’t lose the plot with a gun in his hand over something petty, like Kadam did. You also hope he won’t submit to it all and only introspect on his final day of service, like Patil did.

He’s unusually intense and wears the expression of an adult who seems to realise that he has made a dreadful mistake, but is unable to admit it. He seems to recognise that the double-faced society he is protecting is also the compromised world that is wearing him down. For some, this is a horrific epiphany; for others, like Tambe, it’s a gradual, inevitable descent into insanity. It’s all boiling within though – the injustice, cheating, corruption, the rage of it all…you wonder where he fits in with that uniform. It’s supposed to represent something, but on him it just looks like irony snogging itself: A misfit, and worse, an introvert too, from the looks of it.

But it’s not the day-to-day nonsense that’s getting to him. It’s bad enough having to man the streets and battle raucous crowds during the infamous Mumbai festival season. Those pesky Ganpati Visarjan nights, Durga Puja Mandals…the rare times you actually sympathise with the cops – even the pot-bellied, shifty-eyed, dishonest and greedy ones. For those nights, you can’t really fault them for being complete jerks. The rains don’t help either.

Tambe here is almost numb to the noise. He watches strangers dance with gay abandon to tunes he probably abhors by now. But these are also tunes he hates because his temperament keeps him for shaking “dat ass”. He thinks: There’s something about these chaps, not dancing, but moving haphazardly without a care in this world. It must feel nice. Some of them drunk, some just wanting to escape for a bit, and some of them just letting go. It’s far better than watching them misbehave with their wives, kids or with waiters at shady quarter bars.

But none of these things are going through Tambe’s mind.

He seems to be somewhere else.

He can’t fathom the fact that he is unable to provide his little girl with a decent education. The principal – a lady who probably sells kids’ futures as quick as she makes them – is asking for an obscene amount of money for private schooling. As a cop, Tambe seems to believe he deserves better, but he won’t say it. In a way, he feels ashamed, because he must have perhaps promised his wife a “safe” future working as a proud ‘rakshak’ of this country. But safe isn’t the same as affordable in big cities. He expected his job to have perks, but not ones he couldn’t avail of.

And, oh man, to top it all, these loud meaningless festival celebrations – he should be getting his salary doubled for such weeks. He looks at them like he almost envies them, because they’re able to express themselves better than him. They don’t care about what people think. But people will think – and care – if a middle aged cop like him does the same. He is expected to maintain order when there is none in his own life.

In fact, Tambe would have preferred it if he wasn’t presented with a morally ambiguous opportunity to get out of the hole. That bag full of money shouldn’t have fallen into his hands. If it were in anyone else’s hands, at least he wouldn’t resent his own righteousness. Here, he is forced to uphold his own principles and reputation when nobody is looking – no news channels, social media activists, no kids, nothing. This holier-than-thou attitude is something that must have always annoyed his wife, who is sick of living in squalor by now. He doesn’t even drink, self-destruct or cheat on his wife like the others in his unit; she must wonder why he is the way he is. A semblance of normalcy would have been comforting.

Only recently, I discovered that cops like Tambe are like God – in the sense that you want to believe that they exist, and you want to believe that they’re honest and well meaning and omnipresent, but they’re actually invisible. They’re a myth, a figment of imagination. Which is what Tambe himself seems to realise, too. I noticed how my broker slipped in a Rs. 500 note into the drawer of a police officer in his cabin, with a simple nod of the head and an expression that seems to suggest that this is common practice. The lesser attention they pay to these “bribes” while they’re happening, the more experienced they are in these matters. The broker, too, knew exactly where and when to present this gift – only to get a signature that we should have gotten long back. Basically, just to keep the system running without any speed bumps.

This made me wonder: How do the honest ones survive? Honesty, which should be a basic un-celebrated necessity to work for the law, will be looked upon like a great luxury and attribute (it shouldn’t be; it’s par for the course). Tambe’s face here tells me that the honest ones don’t survive too long. And if they do, they wither away in their own little shell of no occupancy.

Director Devashish Makhija (Oonga) understands this language of breaking down.

He understands that a visual or audio assault on the senses in this state of mind could result in virtually anything. The quiet ones are often the first to react. You’d imagine Tambe would be the first to do the ‘Tandava’ – not so much because of what it symbolically stands (Lord Shiva’s divine dance) for – more so because its unruly, vigorous, non-specific movements are suited to people who can’t dance.

It’s the I-don’t-care dance: the ultimate expression of letting go.

Technically speaking, he goes from the violent, angry initiations of the ‘Rudra Tandava’ into a no-holds-barred representation of (the joy of) breaking free, the ‘Ananda Tandava’. Here’s where it all spills out.

Bajpayee looks so out of sync with his own body that it’s contagious. Even the few minutes of silence that precedes this is enough to convince us that Tambe is now in the “f*ck it” stage of frustration. The stage where the mind decides to leave the body for a vacation – which explains why he didn’t even need to get drunk, and why he wondered what came over him later in the van.

Perhaps this is even how Tukaram Patil turned into who he was eventually, while young Kadam may have walked away because he was slightly more restrained (read: no wife or kids).

If anything, Tambe deserves these few wild minutes, for his own sanity, only so that he doesn’t shoot down someone after he returns from his suspension. I wouldn’t be surprised if his seniors received this absurd piece of news with straight faces; they’re used to this, at least this was a lighter, less harmful nervous meltdown. It could have been far worse.

Tell that to unfortunate auto driver and angry commuter though. They were just in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Or were they?

To watch Bajpayee “act” like that is an event of rare satisfaction on its own. Not since the days of ‘Satya’ has he completely embraced a personality with such lived-in, tempered habits. And that criminally catchy piece of music – who can resist, really?

Instead of breaking down, however, Tambe breaks free – an achievement quite apparent from the final slate of the film. Though this isn’t the same as escaping, it is perhaps a far more relevant resolution in context of who he is and where he works. It’s also the only happily ever after such burdened adults can ever experience. It is a moment they will look back at with fondness, not with embarrassment.

Bajpayee’s final giggle is reluctant at first, as he studies his wife and daughter’s reactions (as he perhaps always does, after behaving the way others want him to), before eventually seeing the lighter side. He is almost relieved, and his mind only urges him to smile after his wife breaks into a chuckle. “Hasi, hasi, hasi…phew!” That he feels like he had wronged her just by doing his job with integrity is a bittersweet indicator of their conflicted existence.

A husband can still make his wife laugh, and a father can still humour his daughter – a slice of knowledge that seems to have dawned upon Tambe. Enlightenment, in many ways.

By RAHUL DESAI

[…] if you’re in it to become a filmmaker, you should have no concerns with all this. Like director Devashish Makhija says, you should probably separate your income source from your creative ventures. It’s just that […]