Director: Mrityunjay Devvrat

Cast: Pavan Malhotra, Farooque Sheikh, Raima Sen, Tilotama Shome, Indraneil Sengupta, Victor Banerjee

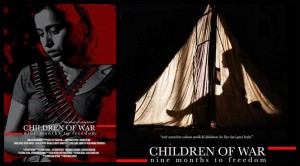

The title, Children Of War, is a universal one; it paints a vivid picture, and immediately, you know that it’s one that cannot be taken lightly.

It is provocative and stirring, the kind that has a reverberative effect if voiced in a hushed tone. It doesn’t promise a bed of roses. Debutant director Mrityunjay Devvrat leaves no stone unturned (literally) to demonstrate one of the most brutal genocides in human history.

Much of its cinematic power comes from the fact that this conflict is forever entrenched into the contours of history and human memory.

The real tragedy of the Bangladesh Liberation war (1971) is often lost amidst mentions of more quantitative war crimes like the Holocaust, but this 9-month long struggle boasts of atrocities and crushed spirits as alarming as any. The filmmakers take a typical separation saga of a Bengali journalist (Indraneil Sengupta) and his wife (Raima Sen), and turn it into an uncompromising, relentless, soul-sucking tale of despair and darkness.

The film begins with a disturbing sequence of rape – both of body and dignity – as officers barge into their home to torture the journalist. Raima Sen’s face is difficult to forget here, as she is mounted from behind; a few moments ago, she was in bed with her soulmate, and just like that, her life is turned into a living nightmare. One always wonders how actors shed their inhibitions and prepare themselves for such scenes – scenes in which their spirits and souls must leave their bodies, in which they must strip themselves naked, down to their last desperate emotion. Such moments transcend acting and the craft. For that moment, they’re real victims, far away from the comforts of modern civilization and whirring cameras. There is no time for basic emotions like longing and sorrow. She is then put into a ‘rape camp’ with many other fertile young women, run by the Islam-extremist Pakistani officer (Pavan Malhotra) who violated her being. His sole mission is to rape and impregnate them, and create an entire generation of nationless children, Children Of War.

The filmmaker allows the minimalist design and geography of this camp – most of which is seen by night, lit by prison-style floodlights and barbed wire – to define a major portion of the lead antagonist’s character and motivations. If one thinks back to Pavan Malhotra and his performance here, it cannot be imagined outside the stifling confines of his favourite camp. His face is as much a part of the atmosphere as the wooden barracks, adjacent stream and deformed bodies.

Malhotra here constructs possibly the most vile and deranged screen antagonist in Indian film history. His rendition is spine-chilling – combining the deceptive deviousness of Hans Landa (Inglourious Basterds), coldblooded ruthlessness of Amon Goeth (Schindler’s List) and scowlish arrogance of Scar (Lion King). He engages and terrifies even in a single-shot sequence, where he drunkenly converses solely with his gun. There is no purpose of this long monologue, except to establish how irrational and demented this man is. And he manages to pull it off despite its lack of context, because for that moment, Malhotra is Malik and nobody else.

The only respite from this carnage is a parallel story of two orphaned Bangla teens struggling towards the Indian border to seek refuge. This track is the only mildly escapist section that forays into the abstract to portray psychological damage. The director’s decision to treat the film as a multi-narrative drama is a wise one, as disparate and visually apart these journeys are.

There is a touch of Hans Zimmer to the music Devvrat uses to dramatize bloodshed, and the effect it has is overwhelming, even at the cost of its indulgent length (150 minutes). Exploitative and loud – yes – but also perhaps a necessary evil to drive home the intricacies of a phase we all seem to have conveniently blocked out, or are completely unaware of. This film, for all its flaws and indulgences, is impossible to escape. There is a loss of innocence all around, much like in today’s world, where lines between revenge and justice are often blurred.

In the sequence of a screenplay, the magnitude of brutality is always amplified if preceded by brighter times. But in Children Of War, there is rarely any cause for hope or joy, where sadness is only succeeded by further despair. And yet, you find yourself more shaken than moved at the end of it all. While the film doesn’t quite transport you out of the conscious experience of watching a film and its elements – and even makes you wonder if a representation needs to be so relentless – it’s powerful enough to make you feel alive. It can’t have been easy to make, and it is perhaps even more difficult to watch. But some films just have to be made, irrespective of numbers and marketability. And some stories just have to be acknowledged.

(The film had a limited release on 16th May 2014 across cinemas in India)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.