Director: Ian McDonald

Editor: Ajithkumar B

Producer: Geetha J

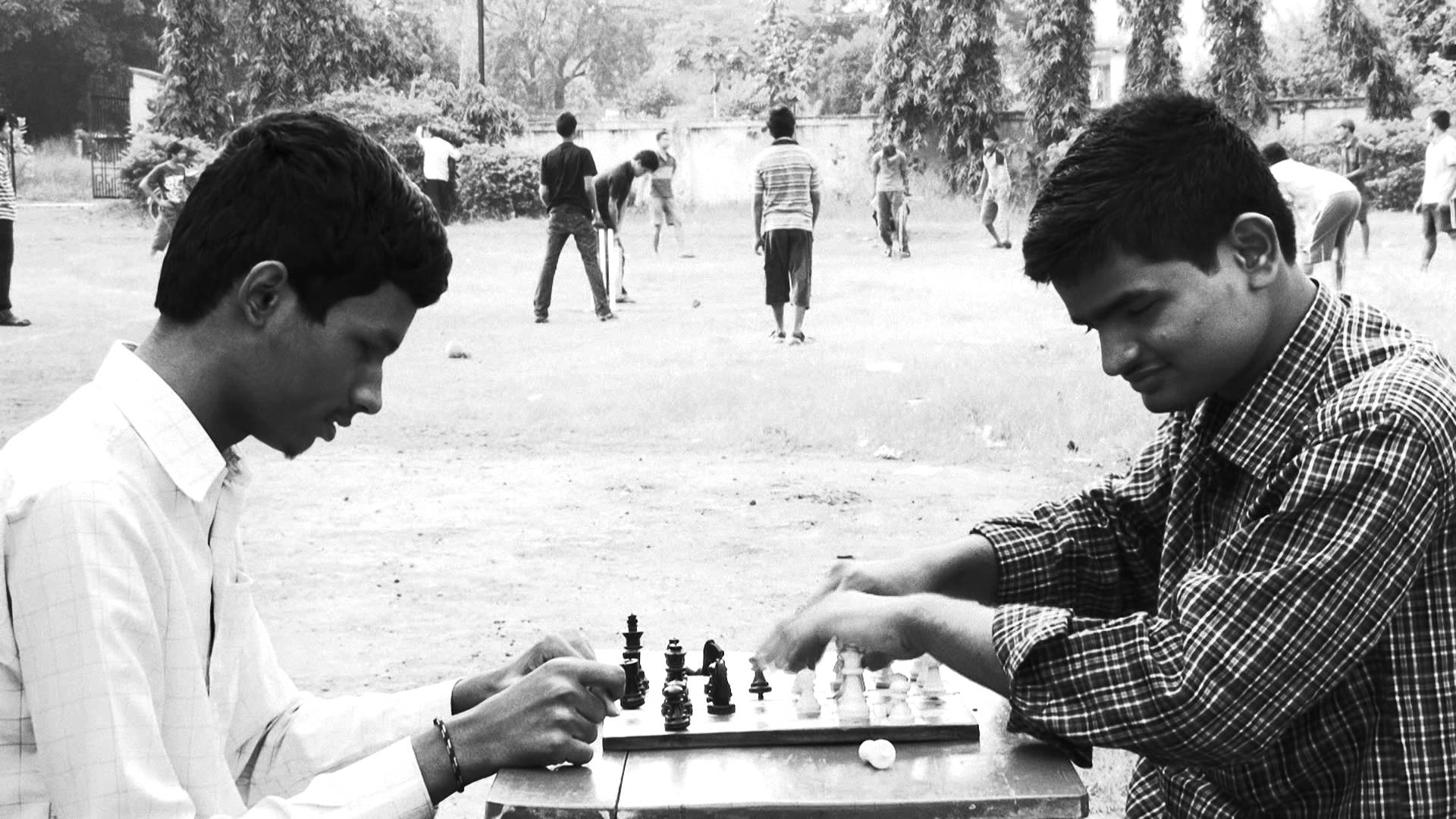

Genre: Documentary (B&W)

“But there is nothing like the sight of an amputated spirit. There is no prosthetic for that!” Al Pacino bellows as Lieutenant Colonel Frank Slade – incidentally a blind man – in ‘Scent Of A Woman’. Slade, a troubled ex-soldier, who has turned into sort of a mentor of the bright Baird boy babysitting him (Chris O’Donnell), defends him passionately in a school Court hearing against his ‘snitch’ friends. These are words you’d imagine Charudatta Jadhav repeating to his junior Blind Chess players; he does, in a way, when he offers them consolatory pats with a well rehearsed “This will make you stronger” after every failure.

Jadhav is a unique man. He went blind in his teens, but unlike Slade, he found purpose in Chess – considered to be more of a cerebral, calculative game than a visual one. But his journey to the top of Indian Blind Chess was lonesome, and not quite of an international standard – something he realized before it was too late. His ‘stagnancy’, as he refers to it while giving pep talks to the kids, was undeniable. And he’s honest about it. He then decided to quit his own career to help build a system that would blood greatness.

Is this another case of an obsessive teacher who wants to account for his own failures through his gifted students?

Not quite.

He has never achieved it, but he knows what it looks like. Ask coaches and analysts around the globe, and they’ll tell you that their own shortcomings are irrelevant – and almost advantageous and necessary – for their students to excel. It also helps that they’re still hungry. Jadhav genuinely wants India to excel in Blind Chess. He knows it will take patience and perseverance – qualities reflected in the filmmaking team as they resolutely follow the careers of 3 juniors between 2009 and 2012.

But often, he loses hope. So close, yet so far, he sighs, looking into the dark horizon – when two of the three come within a game of winning a World medal. He knows that India will have to wait longer for this medal; the strides being taken aren’t big enough. If only this validation came sooner.

Jadhav is seen throughout Ian McDonald’s fascinating documentary – a perpetually omnipresent guru-teacher-advisor-administrator-guide-observer, hovering around lowly State and National tournaments. “I’m here only”, he assures visually impaired players, hoping they find inspiration in his presence. He also often finds himself rooting for results that would further the prestige of his sport, instead of their own individual careers.

Darpan, perhaps the most gifted ‘totally blind’ junior player in India, echoes his foresight. The boy is methodical, eager, calm and collected, in stark comparison to his driven mother. In 2009, when high-ranked Darpan loses to Chennai’s young SaiKumar – another subject of McDonald’s vision – his mother cries foul and loses her cool repeatedly. She knows more than him back then that Chess is what defines him. Three years later, however, she is a different, wiser person when he loses. His temperament and intelligence seems to have rubbed off on her. A victim of the debilitating Steven-Johnsons’ syndrome, Darpan lives a life of to-the-point routines (“I will be back home by 6:07 PM”). Unlike his folks, he is relatively upbeat.

SaiKumar starts as a prodigious talent, but seems to be losing his way. Unlike Darpan, he hasn’t quite accepted that he is visually disabled. Perhaps a sliver of light sensitivity and vision seems to be keeping him in limbo. The youngest, and most emotional of them, SaiKumar has a limited game, as pointed out by Jadhav. His evolution is tough.

Soon, he will be stagnant, like the older third boy, Anant Kumar from Orissa. Somewhere between poverty, uneducated parents and studies, Anant – a teenager – has lost the will to play Chess. He struggles, but his story ends early; Jadhav barely takes notice. He must look for younger, better players now. There’s ruthlessness, but also a feral commitment to excellence and not just participation – something our country must emulate, if we are to be a sporting nation like Australia.

McDonald merges their stories into a neat little snapshot of time. It’s a phase that has a past, and may not have a future, as is demonstrated through Jadhav’s emotional ups and downs. But he knows that passion, too, is recyclable.

I doubt the makers could have done a better job of bringing this little-known community into public view.

By the end, blindness recedes into the foreground. It’s their vision that stands out. A memorable film, if there was ever one.

If you read about a medal being won in the 2018 World Juniors, remember, Charu sir called it first.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.