The Namesake is also the love story of Ashoke and Ashima, where many of us can find the stories of our parents in theirs. In the first meeting, Ashoke and Ashima sit opposite each other, but their parents do all the talking. When Ashima enters the room, Ashoke tries to steal a glance at her but keeps his eyes down. After some pleasantries, Ashok’s father probes Ashima if she understands that she will be going away to a far-off land where she will be alone. Ashima replies that “Won’t he be there?” It is then that he looks up towards her and smiles. The story of Ashima and Ashoke is made up of these quiet and beautiful moments. In another lovely scene, Ashoke shows Ashima the way to the fish market when they move to the US. She replies, what if she got lost. And, Ashoke casually replies, “You think I’d let you get lost.” These expressions display their love and affection as physical affection does not come easy to them. When they go visit the Taj Mahal, Ashoke holds Ashima’s hands. Moments later, Gogol comes to chat with them, and Ashoke quietly lets go of Ashima’s hands, feeling shy in front of his son. When Gogol invites his girlfriend Maxine (Jacinda Barrett) to his parent’s house, he warns her with no touching and no kissing. However, Maxine does not bother. She even gives a peck on the cheek to Ashoke and Ashima, leaving them flustered. At another moment, when Ashoke is in the security line for his flight to Cleveland, he keeps glancing and smiling at her. Before he leaves, he waves his head that he is going. These tiny moments with the beautiful background music accentuate the film’s longevity in my mind.

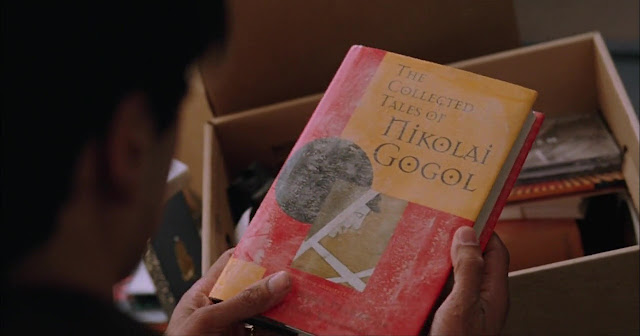

The Namesake also uses the symbolism of shoes. The book has a lot more passages on shoes, but we see a few in the film. In her first meeting with Ashoke, Ashima sees a pair of brown shoes that belong to him. She puts them on and walks a few steps in them. It is a sign of the way she will step in his shoes and become his life partner. In the book, Lahiri writes, “Ashima, unable to resist a sudden and overwhelming urge, stepped into the shoes at her feet. Lingering sweat from the owner’s feet mingled with hers, causing her heart to race; it was the closest thing she had ever experienced to the touch of a man. The leather was creased, heavy, and still warm.” When Ashoke asks her why Ashima decides to marry him, she replies that she liked his shoes. Later in the film, Gogol goes to Cleveland to bring back his father’s body after he passes away. He enters his father’s room and steps in his shoes, reminiscent of the earlier scene with his mother in the film. Now, he is stepping in his father’s shoes, becoming the son that he never was. When Ashoke’s father passed away, he had shaved his head while a young Gogol watched him. Now, it is the turn of Gogol where he tonsures his head after the death of his father. Life has come a full circle.

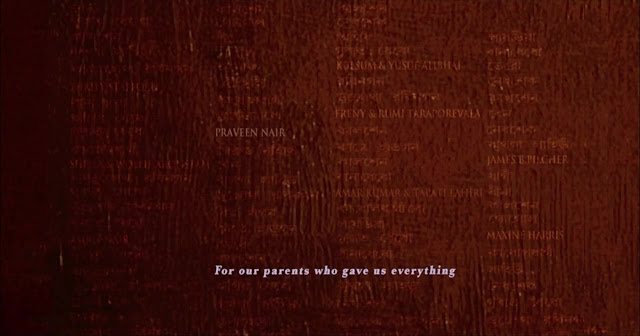

The movie ends with a credit that reads, “For our parents who gave us everything.” Mira Nair said that she made the film after the death of her mother-in-law, who died in a different country. In the film, Ashoke gets a call where he learns that Ashima’s father has passed away. Ashima learns about it a few hours later. After some time, Ashoke’s father also dies. In the book, Lahiri writes, “In some senses, Ashoke and Ashima live the lives of the extremely aged, those for whom everyone they once knew and loved is lost, those who survive and are consoled by memory alone. Even those family members who continue to live seem dead somehow, always invisible, impossible to touch. Voices on the phone, occasionally bearing news of births and weddings, send chills down their spines. How could it be, still alive, still talking?” It is so beautifully written, but it makes me think of living a life without our parents. The guilt of not being there never goes away. Is it abandonment? But is it wrong to have a life of your own without them? When Ashoke left for studies, his mother refused to eat for three days. Again the circle of life has been completed. His own children are moving out the way he did.

In the novel Exit West, Mohsin Hamid writes about the thoughts of an old woman in Palo Alto who has spent her entire life living in the same house in the same city. However, the woman still feels that she is a migrant. While she stays the same, it is the city that changes around her. The priorities she grows up with don’t match those of her children, as seen by their desire to sell her house for a considerable sum of money while she has no interest in the money. The culture and the people around her changed. Hamid writes, “We are all migrants through time.” In today’s world, we, too, are all immigrants in some way or the other. A bit of everything changes daily. We become a little bit old daily. On some days, I feel so left behind in life while the world is moving ahead. The Namesake provides a glimpse into those changing worlds—of culture, of geography, and also of time.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.