By Debanjan Dhar

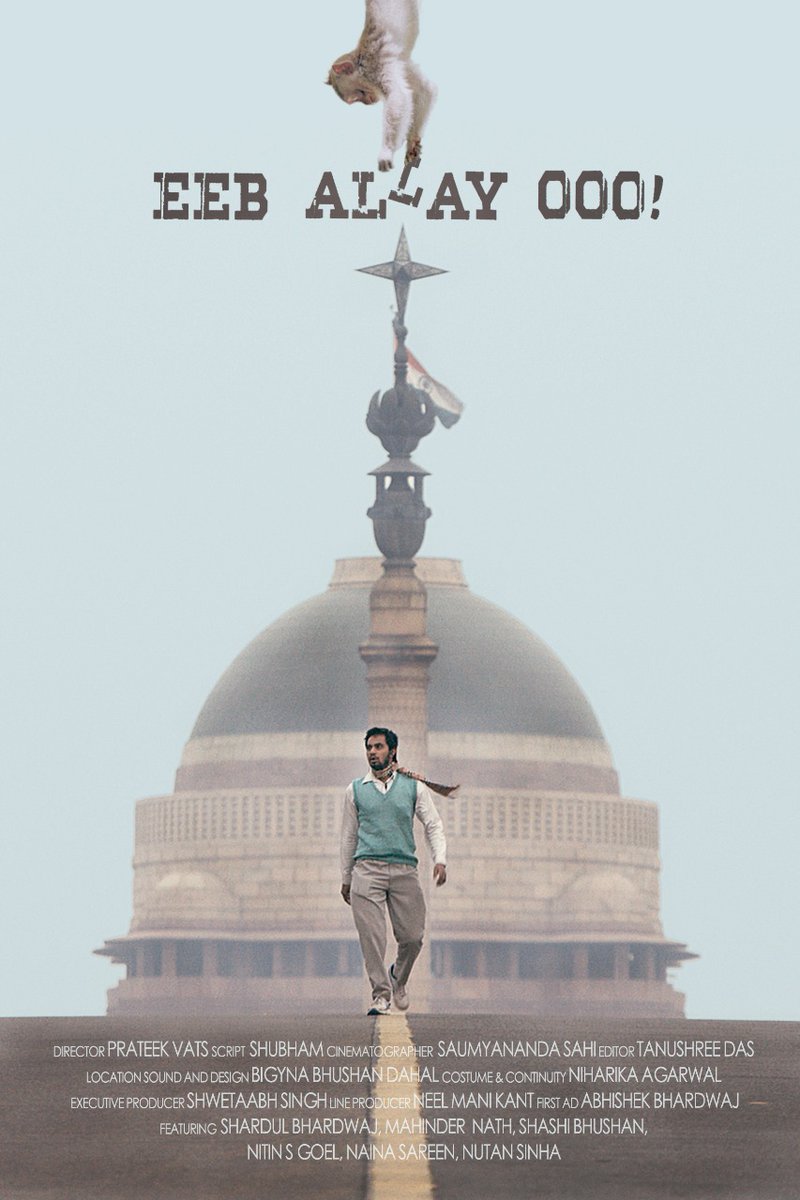

The sole fiction feature film of Day two at the People’s Film Festival of Kolkata (KPFF 2020), Eeb allay Ooo! foregrounds its character, a Bihari migrant, and details his struggles and anxieties as he tries to make his place in Delhi. The protagonist Anjani (which literally translates as The Unnamed in English) negotiates uncertainty and aversion in the lanes and slums of Lutyen’s Delhi; his job makes him prey to considerable mockery. He never quite finds comfort in his work and moves in it rather uneasily.

The magic of director Prateek Vats’ vision is that he doesn’t monopolise Anjani’s plot track as the only narrative framework. He provides space for Anjani’s pregnant sister and scathingly comments on brutal work demands that are totally unmindful of individual convenience and dignity of labour. She is beset by her constant urges for cleanliness in an area overrun by dirt. Anjani is denied the bare essential of a tea break at his work; his employer cashes in on that to conveniently slap pay cuts. Threats of layoff and beggary are always dangling precariously. The relentless talk of gods becoming pests, the divine turning into nuisance and the idea of disrupting the function of the power ladder pervade the film. Vats shrewdly doesn’t spare masculinity either; Anjani’s brother-in-law, a security guard, has a fraught relationship with his fire-arm protection. The men in the film exhibit none of the usual machismo nor egos, they are sensitive and almost crumble in several places. What appears as a character study early on slowly becomes extraordinarily inclusive and accommodative of the people who surround the protagonist.

The film spins a clever, utterly fascinating and wholly fresh take on what lays subterranean in the nation, what remnants of dignity we have with us to hold on to and the troubles unfolding in the republic. The irreverence lifts the film from being just another artistic product of great despair; Vats approaches the epic tragedy that belies the systems with an unmistakeable lightness and levity. It works because Vats relies on subtlety to express his thoughts, and there is no slegdehammering. Working from a smart and keenly intelligent script by Shubham, Vats knows the political climate too well. Shubham’s perceptive writing steers clear of any attempt to push buttons and manipulate audience sympathy for the desperate straits the characters are mired in. Instead he treats his characters with great dignity, and allows them to rely on their own intelligence and manoeuvre through the misery.

The mood darkens significantly in the second hour as Vats plunges us into the final act of a man pushed to extremes, all set to an incredible score. The editing is supremely sharp and the scenes sling by with ease. The sequence in which Anjani transforms is particularly memorable. The structures of power which puts men and women into inescapable conditions are challenged and critiqued.

Prateek Vats reveals a sensibility and worldview very akin to lens of social realism that Ken Loach employs. In several interviews, Vats has talked how the gig economy and the welfare system of Britain in ‘I, Daniel Blake’ has influenced him greatly. Vats mounts a true-blue original take on class dynamics and the prevailing sociological environment in India and slips in grave concerns about the sheer insecurity and instability of the contractual system. He has created a satire that becomes pitch black by the end, and all layers coalesce into a collective symbol, a giant metaphor – and the viewer is made to confront it until there is no longer any hope of escape.

In the Q&A with Trina Nileena Banerjee, Shubham, who wrote the film, elaborated how the film was conceived by Prateek and him as a response to the absurdity of the world around us. The entire shoot took 45 days. Vats’ training in documentary filmmaking had familiarised him with the shortcomings of documentaries, which is why he chose to mix verite with a very cogent humour. Shubham also talked about how the film-institute training made him and Vats afraid of playing around with film and thus the film is an attempt to create something completely sans fear.

The film was received exceptionally well, with laughter and collective acknowledgment of the artistry on display. By the end Vats creates an amalgamation of images, conjuring up a never-seen-before Delhi, and leaves us wondering about the character’s preoccupations.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.