By Rahul Desai

A gigantic warehouse supermarket located off the German Autobahn comes to life after dark. The PA system allows the soothing tunes of Strauss to waft over stacked shelves. Forklifts traverse the empty aisles in a routine that reflects the musical symmetry of a ballet rehearsal. Christian, a newbie, develops a bond with grizzled trainer, Bruno, over parking-lot cigarette breaks. He falls for Marion over stolen coffee breaks at the vending machine. His chatty colleagues customize the post-shift Christmas party with expired beverages and indoor tanning-beds.

Not far away, Endre supervises the factorial ways – from the slaughter of cattle to the processing of meat – of a Hungarian abattoir. He dislikes the arrogant butcher, and gossips with his friend Jeno in the company mess every afternoon. He falls for Maria, the strange new quality inspector.

Christian, the protagonist of Thomas Stuber’s In The Aisles, and Endre, the focus of Iidiko Enyedi’s On Body And Soul, are two of several new-age characters that are expressed through their professional environments. They occupy films that acknowledge the foregrounds of contemporary existence: the modern workspace. To explore the personality of these stories, the writers examine the spaces that its inhabitants earn a living in rather than the ones they live in. Survival is the primary instinct of human nature; there is nothing like a job – a performative function that quantifies the idea of survival – to expose the truth of this nature.

Films like these, Steven Spielberg’s The Terminal, Sean Ellis’ Cashback, shows like The Office and Suits, reinforce a socioeconomic reality of our times that mainstream cinema often strives to eschew: Life itself is only the dot that joins sentences. Families, travels, heartbreaks – domestic events that entire genres of storytelling are built upon – are merely sub-narratives that unravel between the constancy of work. It’s home that separates vast stretches of office, not vice versa. Those like Christian and Endre let the intimate shades of living – love, friendship, longing – infect them in the one space that monopolizes the physical, and emotional, currency of their time.

But the answer to the compassionate treatment of ‘workspace’ stories lies in the culture they represent. The blue-collar atmosphere of In The Aisles features misfits that grapple with social rejection in a setting that big-city cars see as a blur on sparsely populated landscapes. Christian is an ex-convict with a substance-abuse history. Bruno is an ex-truck driver whose personal life is molded with the seclusion of long cross-country hauls. Marion has an abusive husband. The white-collar corridors of On Body And Soul feature Endre, a divorcee with a physical deformity, and Maria, an autistic young lady. The bitter, overcast weather plays a key role in the magnification of outcasts. Work becomes a refuge from the cold sterility of their apartments. Communality becomes the solution to urban isolation. Their perception of escapism and fantasy, then, is tinged with the relative warmth of professional subservience. Filmmakers see the magic in their mundaneness – Christian hears soothing ocean waves, Endre is a deer in his dreams – as an extension of civilization rather than a reaction to it.

This is perhaps why modern Indian cinema rarely allows workspace identities and office walls to define its stories. The ones that do – lawyers, cops, doctors, athletes, artists – are those that enable filmmakers to shoot space and time. Unregulated hours and labour-oriented mindsets turn regular 9-to-5 jobs into a robotic reality that needs escaping from. Moreover, our domestic culture – joint families, parental control, early marriage, stigma of divorce – is based on the eradication of loneliness and individualism. It relies on the illusion of plurality. Home is purportedly where the unresolved conflicts of work find release in. The tropical weather further enhances this outdoorsy perspective of life. This is where films like Rocket Singh: Salesman of the Year and, especially, Shoojit Sircar’s October break tonal ground.

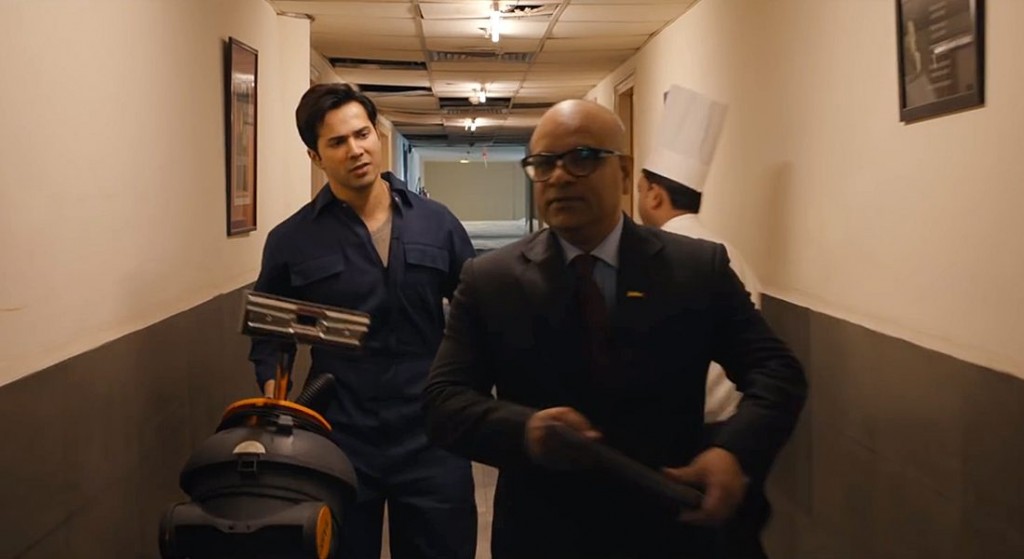

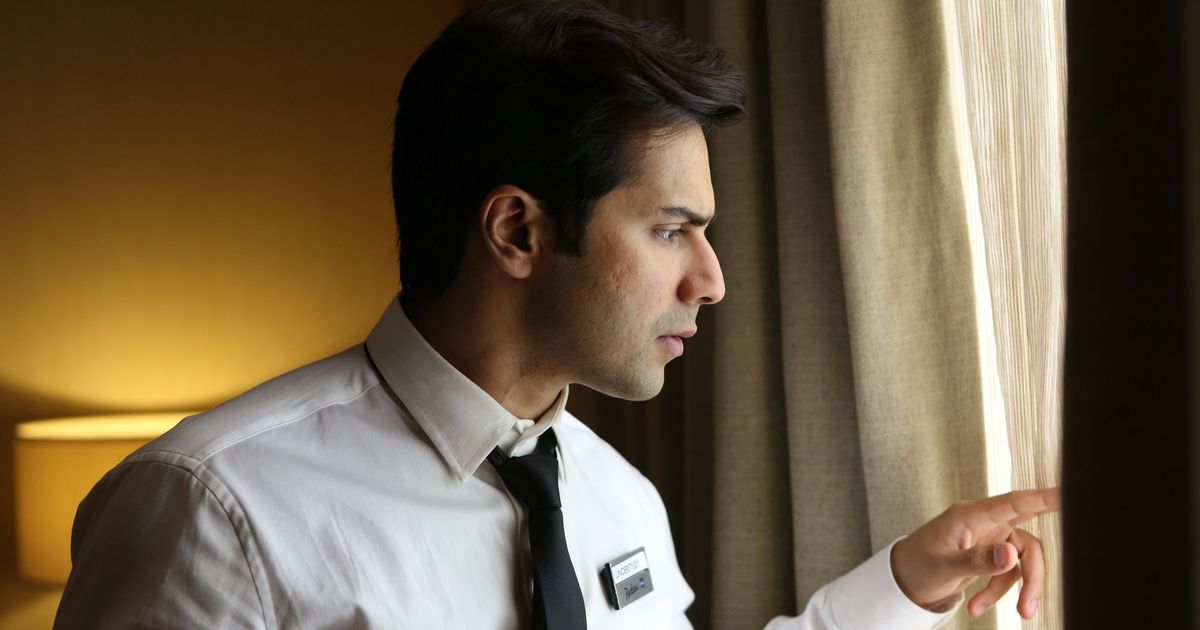

October portrays Dan, a hotel management trainee who abandons his course to nurse a comatose colleague, as both a product and victim of the commercial hospitality industry. He is an oddball trying to swim against his vocation’s inherent dehumanization of caretaking. It’s no wonder Dan goes from being an intern making beds – a decorative task that indirectly caters to consumerism – to being a chef cooking food, an acquired skill that directly affects the consumer.

Most notably, the film lays bare the hidden truth of the young urban professional. Dan is initially a quintessential Indian film in denial of its form: a boy who uses his humanity as an escape from work. He is transformed into a man, estranged from his family and friends, between homes and destinations: a piece of workspace cinema that integrates his humanity into the hotel and its aisles. It ends in October, a month of fall, after which the harsh winter drives even the most ardent outsiders to find solace indoors. At vending machines and makeshift parties.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.