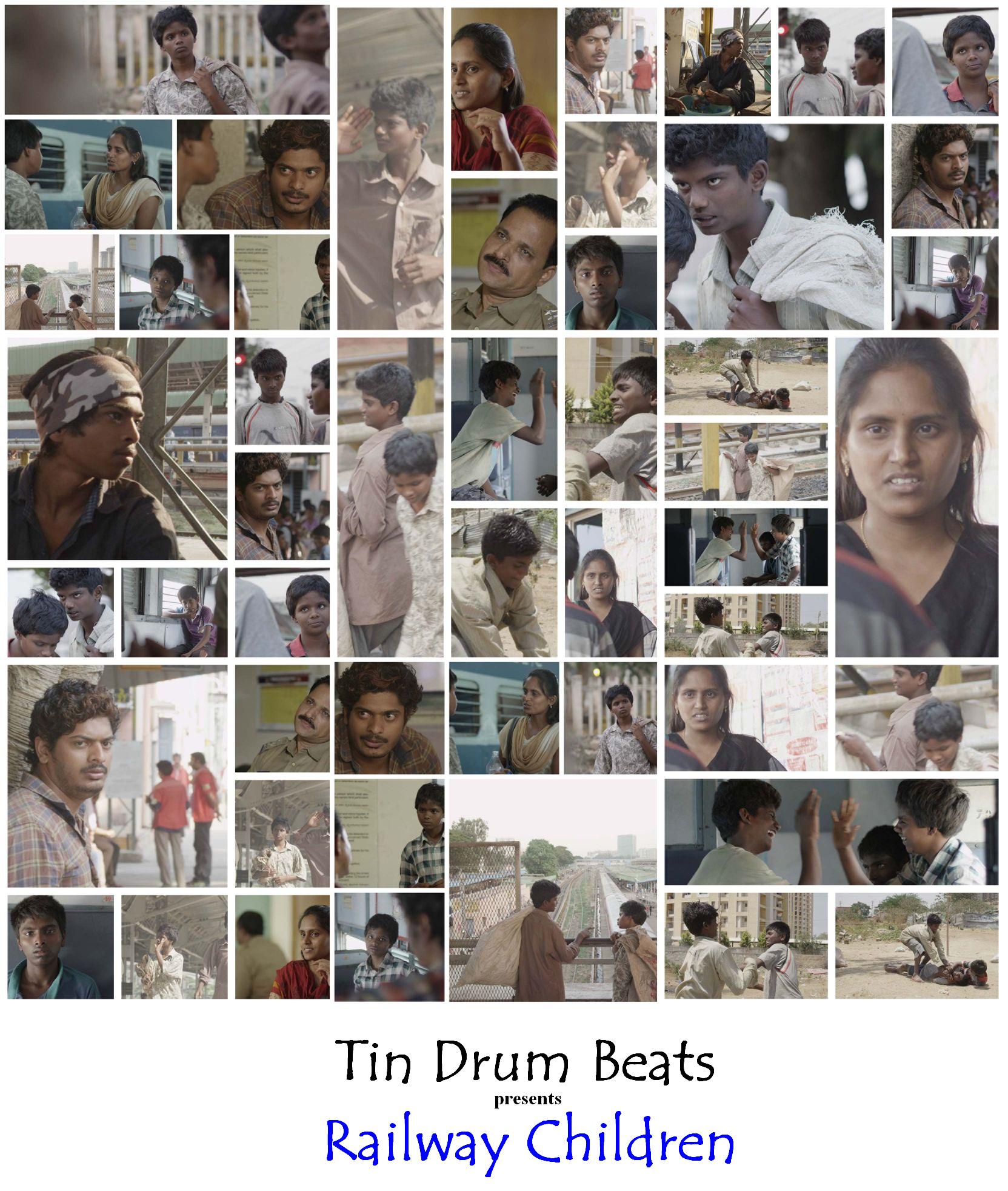

Perhaps the best part of the Mumbai Film Festival is the sheer amount of versatility and variety sections like India Gold include in their line-up. One of these films, Railway Children, is made up almost entirely of children and non-actors, and tells the endearing story of two resourceful railway-platform-dwelling runaway boys slowly learning the ways of their environment.

Snehita Kothari has a brief chat with its director, Prithvi Konanur, about his sophomore film, its children and the overall result of their efforts.

How did you get into the movies?

PK: I am an engineer and have worked in the IT sector for a few years. When I was working in Europe, I started dabbling in screenwriting. My first screenplay (a horror/thriller) was optioned by a UK-based producer for a Hollywood project. While that didn’t happen, I went to New York Film Academy (on his recommendation) to do a diploma course in filmmaking. On returning, I made the short film A Conditional Truce. That’s how I’m here.

Please tell us about your film, Railway Children. When did you decide to make it?

Railway Children is a docudrama that tries to take a peek into the underbelly of the world of runaway children. It also focuses on rehabilitation.

I was introduced to an NGO which was working in this field. When I heard their stories and read the book Rescuing Railway Children by Lalitha Iyer and Malcolm Harper, I realized there is an original story to be told here. It had to be a film.

Any challenges?

There were many ups and downs. The biggest challenge has always been the money, as you may have heard before!

How did you go about shooting on platforms and trains?

With plenty of preparations and rehearsals. We didn’t want to waste time once we were there.

How challenging is it to work with adolescent non-actors? How did you prepare them?

They always come with an open mind. Their innocence is actually a luxury for filmmakers. They’re quick learners and they don’t carry baggage or bad/pre-conceived habits. I conducted an exhaustive workshop for many days to prepare them for the role.

How did you develop the story?

I didn’t have to do much to develop the story. The story was already there. Multiple stories. And all of them, real stories. These are real people, real children dealing with real life. So, it becomes comparatively easy to write such a screenplay.

How did the story change from what you conceived to the final product?

The final product is not different from what was originally conceived. However, the details of the final product are widely and wildly different from what was originally conceived, because actors were given enough space to improvise. So dialogues, smaller details, actions and even one plot point changed completely.

How much do favourites and influences affect a voice or style of filmmaking? Can you tell us about your influences?

Very much. And not just subconsciously, but also consciously. One of my inspirations is the Persian filmmaker, Asghar Farhadi. I also like Girish Kasaravalli’s films.

Do you think the audiences of today have started giving preferences to realistic cinema?

I wish that were the case. But we see a lot of such films becoming commercially successful. In India, I think this is partially because ordinary Indians are not exposed to world cinema or the cinema world. They’ve been trained to think in a certain way by our popular cinema.

And another point that adds to this is, film appreciation is not something that our students learn either formally or informally.

Does it bother you festival films do not generally have a viable commercial market?

I think it is changing. Slowly but surely, film markets are opening up at Indian festivals too. Another important thing is, among the educated Indians who are exposed to world cinema, a new appreciation for such films is developing. So, that will surely provide a market for such films.

What is the one reason audiences should watch your film at MAMI?

I’ll give you three: performances by the actors, performances by the actors…and performances by the actors.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.