In an industry replete with stubborn old-school directors refusing to embrace change and evolution, Hansal Mehta is a rare creature. The proverb ‘ageing like fine wine’ only applies if one is already great to begin with. With movies like ‘Dil Pe Math Le Yaar’, sex comedy ‘Yeh Kya Ho Raha Hai’ , ‘Woodstock Villa’ and doomed underworld tale ‘Raakh’ to his name between 2000 and 2010, even Mehta began to wonder if he had a voice at all.

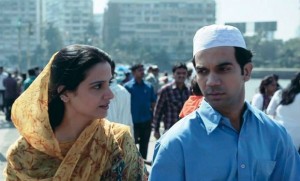

But with Shahid (2012) – an honest, hard-hitting biographical drama on slain lawyer Shahid Azmi – Mehta not only reinvented himself, but literally resurrected his own filmmaking career 15 long years after he made his first. He has been around since the early 90s, but many believe that he has only now really started telling stories.

He looks back, every now and then, if only to examine how that ‘dark phase’ made him the artist he is today. Now, after the well-received ‘CityLights’, he awaits the release of his bravest film so far, ‘Aligarh’, which premiered at the 2015 Mumbai Film Festival. In his own words, he is “making up for lost time.”

Here, Hansal Mehta speaks to CHINTAN BHATT extensively about his journey, his mistakes, lessons, Rajkummar Rao, Manoj Bajpayee, film criticism, independence, politics and a bit more.

How was the ‘Aligarh’ screening at MAMI? What were the reactions like?

HM: It exceeded all expectations. I was a bit concerned when MAMI told me that the screening will be held at Regal cinema. So that was the first scare: the cinema hall is old, so the quality of projection, sound was a concern, and that it was such a big hall with a capacity of over a 1000 people. But there were lines and queues outside the theatre. It was sold out way before the screening and the quality of projection and sound was very, very good, so that exceeded all expectations. And secondly, the response that the film got was very consistent with what we got in Busan, London and everywhere we went. People have been overwhelmed, moved and they feel it’s a very important film.

I was watching Chhal the other day and some of your other work, Dil Pe Mat Le Yaar, and I could just catch the trailer of Raakh (2010)…

HM: Raakh is best forgotten…

But there seemed to be energy in those films. Can’t quite point it out, but a different kind of energy. How do you look back at those films?

HM: At every stage in life, I can look back and say that I tried everything. Dabbled in different genres, and I continue doing that. I am constantly exploring, challenging the way a script can be approached. A script is written; there is a conventional way to approach it, and there is a challenging way to approach it, and I am trying to find the challenging way. It’s always been the case. So when I look back at ‘Dil Pe Mat Le Yaar’, ‘Chhal’ and even ‘Jayate’ (1997) – from a 26-year-old debut filmmaker, Jayate had a lot of silence, it held back a lot. And I could have approached that same film in a very different manner. That was the age of loud melodramas. And I approached it from a completely opposite direction. It was not the popular way. I have challenged this popular method consistently. And right now, I am on my 12th film and I have not done badly. I have not made path-breaking cinema, but I have tried different things. There have been indifferent films in between, but I tried. I have also made a B-Grade sex film, a sex comedy.

The stories you have chosen have been varied. Does the selection of ‘Ye Kya Ho Raha Hai’ and ‘Shahid’ come from the same place or you think you have evolved into selecting different stories now?

HM: I don’t know. As for ‘Yeh Kya Ho Raha hai’, I think your state of mind drives you to make your choices. I was a young filmmaker who was in a bit of a desperate situation, so my desperation drove me to some of the choices I made. And having said that, I stand by those choices as they served the purpose at that time. They fulfilled my need for money, or the fact that I was trying to break into a more mainstream space. So, they provided me an inroad into that mainstream world. I cannot completely disown them.

But you can be objective about them?

HM: I am completely objective. I know that I was not cut out for them, and I did not make them well. I made some terrible films. So I am very objective about the fact that they are terrible films.

Given that your choices and films have been so varied, has your process working with actors evolved over the years?

HM: It has evolved. Over the years, I have begun to understand myself, the essence of human interaction and human behaviour much better. I am able to communicate with actors perhaps based on their process. I am more sensitive to an actor’s individual process.

Adapting to them?

HM: Adapting to an actor’s own process. And then directing the actor based on his process, based on his comfort and mind space on location.

Can you give me an example?

HM: Manoj (Bajpayee) does a lot of preparation, but he doesn’t necessarily want you to be a part of it. So he asked me for an Assistant Director. It’s not that he wants me to do a workshop everyday or sit and read the script 20 times. He asked me for an Assistant Director who was a Maharashtrian boy. His name was Asmit. So Asmit would spend 2-3 days in a week with him, up to an hour with him some days, and Manoj would speak to him in Marathi, and that was it. And then Manoj would spend time with his makeup man, talking to him in Marathi, observing him. That was his process: doing things, observing people around him, watching videos of Professor Siras. He was watching videos of some other Maharashtrian poets and doing his own homework.

The only thing that has not changed is that I improvise. And the character is growing, building in my head. On set, if suddenly I feel the location has that organic energy, I put the actor who is playing that character in a situation he/she is not prepared for, and that challenges the actor and pushes him/her to explore the characterization deeper beyond the script. That’s what I do, but I think I do it better now. I have perhaps seen more (of) life now to put it on film now.

You do that with your crew as well?

HM: It’s always that way. We shoot in very claustrophobic, crazy locations, which are not shooting-friendly. So my DOP has that constant challenge of building a visual style, given the limitations of locations. The biggest problem I always work with is the budget. Films are always made at a budget less than they could be made at. So the first challenge is that the production crew is always under pressure, and the rest of the crew automatically falls into that well of pressure. I work under budgetary challenges, as I don’t see that as a major pressure. Another challenge is that I shoot a lot of material not necessarily part of the script – like that whole moment in Aligarh where Professor Siras is listening to Lata Mangeshkar; it was not scripted. It was something about that room, and that moment, something about that character’s loneliness that I wanted to explore. I think that moment is one of the highlights of my career. Also that courtroom scene in Shahid has also been a highpoint in my career.

Those courtroom scenes in Shahid – they looked more authentic than anything else we have seen in that space before.

HM: Well, the film ‘Court’ had its own take on courts, but yes I can boast about Shahid, because if you look at those court scenes, they are conventional Hindi scene drama. Even if you read them, that is what they are: a sense of reality, but they are not real. They are still melodramatic, but how do you make melodrama real, because melodrama is actually engaging. I have grown up on Bollywood movies, I have grown up on masala. So I just try to make this ‘masala’ more edible.

Those courtroom scenes merged the melodrama with the production design, visual style, and even acting, which was so distinct and real, because it fed off the atmosphere.

HM: That’s the thing. It’s about the marriage of all these things. Even ‘CityLights’ on paper was a hardcore Vishesh Films melodrama, and my challenge was that I shot it without lights. The first thing I told the cameraman is that there will be no lights on set. It was shot in actual locations. I made the actors travel by train, lead a tough life and suddenly it created a sense of reality. I borrowed from real life. It’s just that we made them larger than life. Misery is not melodrama; it is something happening around you. Our films make them larger than life, and make them hammy. Here, of course, it is softened by the fact that you have actors like Rajkummar (Rao), Manoj Bajpayee. They understand that challenge, and you cannot pose such challenges to dummies. My improvisation – creating all this material, subverting the material at times, taking a written piece into different directions – poses challenges to the editor. He reads it, sees the material and says, “FUCK, THIS IS NOT IN THE SCRIPT!” So it’s a challenge for him, and I give him the freedom to shape the narrative. But it’s a challenge because he is constantly on his toes too; he does not have a piece of paper to rely upon.

The last few films are based in such specific worlds – not the exact world you come from. How do you prepare for them?

HM: It’s a world I have lived in. That’s what I am saying: my recent work is better than previous output as I have seen more of life. More experiences, more joys and tensions. I have met different kinds of people and I have learned to merge my life experiences into characters and their behaviour. I sort of connect the two. I have spent a lot of time now in our roots. Like ‘CityLights’ was rooted in a place I have spent time in. In Rajasthan, in a village, it is rooted there. Shahid is a character I have spent my childhood with – who, all of a sudden, after 1992-93, were labeled as terrorists, and as anti-nationals. I have seen their lifestyles and I found them no different from mine, except the fact that the mother covered her head or wore a hijab. We played cricket together, but after 1993, things did not remain the same. So I borrowed out of snatches of inspiration, snatches of imagination, snatches of their lives.

I grew up in Ahmedabad – a city with extreme polarizations, divided by a river with the majority and minority living on either side. And when I used to ask my mother growing up why she would have a problem with a Muslim, she wouldn’t have an answer to that. Just that there is a problem.

HM: I grew up with that too. I remember my Naani telling me, “MARRY ANYONE, GET A CHRISTIAN BUT NOT A MUSLIM”. And I wondered, WHY? And the irony is – this is the subversion – I married a Muslim. Not because she said not to do it – I love my Naani like crazy – but this was the prejudice. And I have grown up with that. Your life gets richer by experiences. And I think somewhere through failure also – there was a period of massive failure between 2001 and 2008. 7 years of constant failure. And going lower and lower, and I think that taught me a lot. Because failure takes you to weird places. And after 2008, I just stopped. And you sort of relive those moments, that time. I spent time in court in that failed period. I was standing in the court like an ordinary criminal accused for some silly dispute with other people who are accused of murder. It was just for few hours, but it just put me in the middle of that action and I think I borrowed from all that. I am constantly, shamelessly borrowing. From my father’s life too – I lost my mother in 2012 and it left my father very lonely. Just a month before their 50th wedding anniversary, my mother passed away. And it left all of us very empty. But it left my father very lonely. So somewhere in Aligarh, I transposed his loneliness into Siras’s life.

Coming to editing, you and Apurva Asrani were both in a bit of wilderness and then came back and are creating a good body of work. Can you talk about that association?

HM: I always liked working with him because he challenges me. I normally challenge people, but he challenges me. He is very argumentative and I realized that impacts the work we do together, because he is argumentative and does not give up. We had a very pleasant experience doing ‘Chhal’. That film I thought was very interesting, an interestingly styled film, and very interestingly edited. After that he disappeared, I disappeared. We didn’t fall out, but we didn’t work together after that. He also left for some place. When I came back, I was actually working on something else, and got back in touch with Apurva. I asked him to look at that script and be ready to work on that, but then Shahid came along and I put his name on the poster without asking him. He was living a very peaceful life in Bangalore, so I think I got the chaos back in his life.

What are your views on the state of film criticism currently?

HM: There was a time when I used to be very affected and take it personally. But now I don’t take it personally. A bad review upsets me, but I just feel that criticism itself is not balanced. But having said that now, everyone is a critic. There is very little qualified criticism. You have people like Baradwaj Rangan (The Hindu) standing out in the crowd. He did not write a very good review for CityLights, but I even went on his blog, commented and complimented him on the review, because his review keeps me alive, and his opinion of my film helps me introspect. But I don’t see that type of criticism anymore. I used to enjoy Khalid Mohamed’s reviews when he was actively reviewing. I still enjoy whenever and wherever he writes. Criticism is also writing; there is an experience you are recounting in that many words. And those words have to be fun to read. It has to be a great read. I am not finding a lot of that. The fun of reading reviews is gone. There are key phrases like “film is long in the first half, picks up in the second half”. It is a silly template. They just divide a film into first half and second half. How can you divide a film? Their understanding of editing and cinematography as a craft is also very poor. They refer to sun soaked beaches and note that “the cinematography is brilliant”. It’s the sun! There is much more to the craft; the overall mood that the cinematographer creates and evokes within you, the emotional impact of his work, the mise-en-scene that the director creates. Nobody really understands all that. Editing for them is always “the film should have been shorter and tighter”. Editing is not about taking the scissors and chopping things off, yaar. It’s about building the narrative. Every film has its own needs. I wish the critics understood the processes involved in filmmaking better, and then came from that place to write about it. And I wish they wrote better.

But there are people who stand out. Rahul Desai is a young critic whose writing I enjoy. I don’t agree with him. Critics are there to disagree with. But I enjoy reading him. I enjoy reading Raja Sen. He writes well; he is fun to read. I disagree with him all the time, very violently too. But that does not mean I don’t enjoy reading him. At least make the read engaging and enjoyable. You are using so many words and its not engaging? It means you don’t understand the different departments of filmmaking well enough. I am against that template-driven critique, and then trade gurus turning critics. So film criticism is now very bastardized. Earlier there were fewer people like Khalid Mohamed & Iqbal Masood, and few really good writers who kept that art alive with their own biases. I don’t have anything against that bias. Critic’s bias is part of his experience – which he recounts on paper. He goes with that bias; he is a fan of a particular kind of film or a particular actor or filmmaker. And from that place, he recounts his experience. I have nothing against that. It is something personal. At least there is something personal in your recounting of the experience. I find this talk about being objective very shitty too. Nobody is objective. I am not an objective filmmaker, so why should the critic be objective?

What about your selection of stories? Do you hear a story that touches you and then find your viewpoint in it, or you see something which affects you and you try to find your story in it?

HM: I think it’s a very instinctive process. You get attracted to a story by instinct, and then you start working on it. Now if you persist in the process of writing it, working on it, pitching it, the entire process of making it, then that story stays with you. There are so many that you abandon – some midway, some where you write 10 pages and then you start drifting away. Some get made, and some remain on your hard drive. Like Aligarh was an idea that came to me from Ishani Banerjee. She wrote an email, I saw it and it attracted me. Within a week, she was in Bombay and she was signed, and she was already making plans to move to Bombay. I had already spoken to Apurva to look at the idea and mould it into a script. And there was no producer in sight at that time. There was nobody really to put money into the film. My friend Shailesh who had made ‘Tanu Weds Manu’ said he will invest in the development. So we invested in the development and persisted, not really sure if it will get made. Who will make a film about an intellectual gay professor? But it got made. I moved around with Shahid for a year ever since he died and nobody was really attracted to the idea. The first question always asked was “Who Will Play Shahid?” which was enough to dissuade, because nobody wanted to make a film with me. But I persisted and reached a point where I said I will make it at any budget – give me any money, give me 5 lakhs & I will make it, I will make it with an I-phone. I didn’t care. It started with Canon 5D on which half the film has been made. Rest of the film has been made with cameras that were available on that particular day or during that particular schedule. It was made on a process over 11 months during which shooting was fragmented into 2 days here, 3 days there. It was finally some 39 days of shoot spread over 11 months.

Do you think looking back those shortcomings enhanced and affected the film positively?

HM: Yes, that made the film special. There is nothing more pure than the process of making the film. After that, everything gets soiled. It gets soiled by the way people see it, by the way it is criticized, by the way you peg it to the public in your marketing, so it slowly becomes soiled when it becomes a product for consumption. But I have learnt to accept that, to savour the beauty of that process and separate what happens to the final product, because that is often out of your hands. So ‘CityLights’ remains very special to me because the process was beautiful – the amount we travelled, it gave me insights into my own city, it allowed me to work with wonderful actors, and it was also a challenge that there was a new girl who was not a trained actor with a major role. Even in ‘Dil Pe Mat Le Yaar’, the process was incredible. We were trying new things. We used something called the ‘Bleach Bypass’ process on film. We didn’t have DI or anything at that time, and we were trying to explore a new visual style of telling that film, and unfortunately not many people have seen the film on celluloid. I don’t have a print anymore. But the celluloid version shows you how that process is used to tell that story. So, that remains special to me. I learned so much about film and how chemical reactions help you tell a story and how the amount of silver nitrate on your negative helps you tell a story. This process is irreplaceable. My film might be 60% of what you expected it to be, but for me it is special, it is pristine. In Chhal, we perfected the process when we used it there. There was a conscious attempt to keep the camera off-balanced.

I remember seeing Chhal when I was very young and the style in that film was not something we had seen before.

HM: Yes, the camera was always at a Dutch angle, it was never straight. Today when I think about it, I wonder if I was mad; throughout, we saw the film from this canted perspective. There was this bleach, and I never bothered about the smoothness of the camera movements. We would shoot and then Apurva would take different takes and put them together as one scene. It would be a combination of different takes, no continuity, and jump-cuts all bound together by music. And then I worked with somebody who had a big name in the commercial circuit. I worked with Viju Shah who was hardcore into the commercial space with Mast, Gupt and other such films. He made a really phenomenal, dark kind of soundtrack. That process is irreplaceable. The fun I had making music with Viju Shah; he was a maestro. The first electronic composer, much before Rahman or anyone came into the industry. That process of working with him will never come back. Even in ‘Yeh Kya Ho Raha Hai’, it was phenomenal to work with Shankar-Ehsaan-Loy just after Dil Chahta hai, and with Javed Saab. There are memorable things you take away from work that wasn’t necessarily great. For Chhal, I remember I took two struggling music directors to meet my producer and he kept refusing. He kept saying no and that it was too risky, and they came with guitars and kept singing for hours and pitching. I worked with one of them, Jeet, on Citylights. And his partner was Pritam. I was trying desperately to sell them saying that these guys are damn good. And both of them are now big names. When I was in my low phase and we were looking for new heroines, I remember I used to keep seeing her on TV as a model and I kept going to producers telling them that there is this model called Vidya Balan, and I want to cast her as my main lead. And they would say “AREY YAAR, SHE IS VERY BEHENJI”.

Even the actress, Prabhleen (Sandhu) in Shahid, was remarkable in the film.

HM: That was again good casting. Mukesh (Chhabra) did the casting. Mukesh was a virgin at that time. He had just done (Gangs Of) Wasseypur, some other small film, and was working out of a small room. For every audition, Rajkummar had to go there. The actors auditioned with Rajkummar and he did scenes with them, just to make sure how Rajkumar and the actor looked in the same frame. Now we don’t have that kind of patience or energy anymore. So nearly 6 to 7 actors auditioned with Rajkummar. And somehow it felt forced, even though they were good actors. And this girl Prabhleen came along; she was a totally instinctive choice. Prabhleen is connected to the producer of the film, Sunil Bohra. There was this fear, you know, that “Producer Ki Girlfriend ko cast kar liya”. But he himself told me not to cast her. But I still called her and the first shot she gave in the audition, I looked at Mukesh and Rajkummar, who signaled saying “terrific!” She was not from any acting school, and didn’t have modeling work to support her, so that’s the thing. Your instinct drives it. Even in Chhal, Prashant Narayanan was not in the list for that role. I wanted to cast Aditya Srivastava for that role, an actor I really admire. For some reason Aditya could not do the film, because he was committed to some other film. He backed out at the last moment. Then I approached Atul Kulkarni, who really did not take fancy to the script. I kept pushing the producer for Irrfan who was not really a known face at that time, and my producer kept pushing back for Irrfan.

One night we were having dinner and we met Prashant. He just came and told me that you will never take me in your film and all that, and walked away. Next morning I called the producer asking him, what about this guy? The producer was okay with him because he was very popular on TV at the time. I messaged Prashant, and he asked me to send him the script. And he asked if I was sure this is the character I want him to play, because nobody had offered him a lead character. Kay Kay was my choice from day one too. I had done TV with Kay Kay. When I chose him for TV, that was also instinctive. I chose him on a whim. I saw him from his pictures in a play, and I worked with him first in 1995. He had never faced the camera then. Even for Aligarh, Mukesh Chhabra asked, what about Manoj? And Manoj is my oldest friend, yet he was not in my mind. You have the more typical choices in today’s times. And the difference between Aligarh – the way it is now and it would have been had I followed conventional wisdom – is Manoj Bajpayee.

I was watching Mani Ratnam’s interview and someone noted that there was so much craft in his earlier work, Iruvar, and all those earlier films, which has sort of given way to issue-oriented dramas instead. He said it’s part of growing up; he is more affected by issues around him now. For you too, there is such a huge change of craft from the films before “Woodstock Villa” and the ones after that.

HM: I always wanted to do that. I wanted the camera to observe and not be so obtrusive. Once you know how to use a camera, how to build a scene using it, you can misuse that craft. You move it too much. There is so much technology at your fingertips. You can put a jib, fancy dollies, you can really play. It is mistaken for good filmmaking. And I succumbed to that. I was getting work, and they wanted me to replicate Chhal. But when producers said that – what they meant was something slick, very stylized and I also took that seriously. So I played with technique which does not tell a story. I got back to my roots and observed.

Slightly off topic now, do you think the extreme polarization and negativity on display in the country recently was always there and is only now coming out, or do you think it is a recent trend?

HM: It’s always been there. This a polarizing force and there is a pseudo polarizing force. The Congress unfortunately all these years has been this pseudo-secular force that secretly polarizes, but from the outside it follows this very socialist kind of agenda. So you are confused. A film like Shahid is confusing at that time, in a sense that, you know, even with all these things, we treat everyone as equals, we give them so much, and we do so much for the minorities. And when a polarizing force comes into power – which is the extreme right wing or the extreme left wing, suddenly those differences crop up. It will happen if the left wing also comes in too; the rich and the poor balances will suddenly shift. Right now, it’s all for the rich and nothing for the poor. In left wing, it will be all for the poor and the rich will feel suffocated.

True. For example, I was just noticing that in the Delhi Odd-Even car debate, so many from the richer, affluent classes are opposing it majorly…

HM: Yes, but I see a positive side to it as an artist. There is a constant persecution if I raise my voice; there is a rabid force that completely attacks you. The establishment encourages that rabid mentality, trolling and all. But the result is that this voice of dissent becomes very loud and clear, no matter how many people are opposing it. Earlier, that voice was muddled.

Bollywood is so clearly split with political views, but isn’t that good that everyone is open and clear where they stand, instead of it being muddled?

HM: Yes, yes, it’s for the first time in my stint of 22 years that there seems to be a political stand. Otherwise we have been really sissies. We run like a herd after anybody who is ruling. Even now, not enough people are raising their voice. Few people like me are seen as left-wingers. I am not. I detest the Congress as much as I detest the BJP or the RSS. I am anti-establishment. I hate the establishment. I detest the establishment and its attempt to divide the common man and treat him like a servant. And making policies that are anti-common-man. So I support neither.

It is just assumed that you support Congress.

HM: And I detest that. I find them terribly elitist, pseudo intellectual, pseudo secular, smooth talking fakes. With the right wing, there are at least learned, well-spoken individuals whose minds are completely brainwashed. They are the Indian Taliban, in a way.

Are you optimistic?

HM: I survive on optimism. Been making films for 18 years. In 1997, I made my first film. In 2017, I will complete 20 years of making movies. I have been around since 1993 making ‘Khaana Khazana’. So it’s almost 22 years and I have survived. And in the clutter of all this hatred, people like us have survived, and that’s the vibrancy of this country. I am optimistic not with the current establishment; I want a new establishment to take over, and I am supporting that. There has to be a third alternative – not these jokers. Otherwise, it’s just one replacing the other. There has to be something new, a new ray of hope. And it will emerge if people like me, who are likeminded, continue to voice their opinions fearlessly. Fear will stop everything and there are enough fearless voices.

What do you think of returning awards as a protest?

HM: It’s a symbolic gesture, that I will return my award as a mark of protest. I will raise my voice. I don’t think it’s my business to comment on somebody else’s sentiment. It is a result of that person’s sentiment and gesture. I just speak for myself. I cannot just say what is right and what is wrong. What is right for me is wrong for you. I respect them for raising their voice and at least doing something that is symbolic, if not necessarily effective.

Recently some filmmakers who had made mostly Indie films tried their hands at making big budget films, and it got mixed reactions. Why do you think that transition is not happening successfully?

HM: It’s a battle of expectations, I think. You expected something from that independent filmmaker, and it is unfair to load somebody at heart (who is) a filmmaker. He is making movies, trying different things, so this is part of his journey. It’s a leap of faith he is taking every time he makes a film. I have observed Anurag Kashyap’s journey from ‘Paanch’. He made his debut as my writer in ‘Jayate’. I have observed his journey since even before ‘Satya’, when he was struggling to understand how to write a screenplay. He has always taken a leap of faith. ‘Paanch’ did not release and he made a ‘Black Friday’. He made Gulaal, Dev D, Ugly and then he made a ‘Gangs of Wasseypur’ kind of film. He also made ‘Girl in Yellow Boots’ and then ‘Bombay Velvet’, so there is a constant leap of faith. Now this leap of faith is seen with a magnifying glass. It is incidental that you have a star in your film. If Anurag wanted to cast Ranbir Kapoor, Ranbir wanted to work with Anurag. The corporate backed Anurag’s vision and the star wanted to work with Anurag. I think it is unfair to cast aspersion on the person’s integrity towards his craft. It is okay to not like what he has done, but see it with the same lens. Don’t change the lens when a person makes that transition.

I think this arises from the urge to compartmentalize everybody.

HM: We do compartmentalize, we don’t look at it through the same lenses. Watch Anurag Kashyap for Anurag Kashyap, and within that body of work, if you don’t like his films then it is okay. Nobody else has taken that leap. It was Anurag and it was an ambitious leap. And Anurag has always been an ambitious filmmaker. Gangs of Wasseypur first came to me. If you read that book on it, the first chapter in it is how it first came to me. I wanted to make it but could not find the means, and could not find the producer. I had spoken to Manoj about it. And then the writer Zeeshan went and narrated it to Anurag. Anurag called me, and I just told him to go ahead and make it yaar, I don’t have the means, don’t keep these boys hanging. I never thought it would turn into two parts. I thought the material was less for even a single feature film, it was that limited. There were incidents, there was no story, and we were struggling to make a film around those incidents. He went and made a five-and-a-half-hour film out of it. There is a lot of audacity in what he does, and we have to credit him for that. Even Bombay Velvet was audacious, if not entirely effective.

Do you think the Indie filmmaking here is getting better with time?

HM: You know this word “Indie” – I have a problem with it, there is nothing like Indie. It is a state of mind. My films have been considered as Indie too, whether Shahid or Citylights or Aligarh or the one I am making now, but all my films have in some way or the other been acquired or funded by studios. So they don’t qualify as independent in that sense, but they are independent spirited, independent of formula, independent of the safe route that the businessman will take while investing in a film. So it is independent, and for me that is Indie. The studios have monopolized the whole distribution sector. So we are far away from making those Indies and releasing them successfully. We are very far from that. Numbers don’t support that. Masaan, with all its cinematic merits, did not recover its cost. There is a spirit with which we make films, and you have to marry that with the system that is prevalent right now. Use that system to tell independent stories. And I have been doing that since 1997 actually. I call myself a self-proclaimed “father of Independent films”, much before (Sriram) Raghavan or Kashyap or anyone. Before they came in, I was making those films. Jayate was very, very independent. So was Dil Pe Mat Le Yaar or Chhal; they were not backed by NFDC.

There was a time when those (type of) films got made only by NFDC. Nobody else was making them, and filmmakers in that space were also the same. There was Govindji (Nihalani), Shyam benegal. The same lot that made parallel cinema in the 80s was making films in the 90s too. There was no new voice. There was Sudhir Mishra who was transitioning from the 80s to the 90s. In that sense, when I look back, I realize that I was the first one who did all this at a time when nobody was making it. And it was destined for failure. Audiences were not prepared for it. I was not prepared to slog it out for many years. Still, for those 6-7 years, I struggled to tell those stories and I did manage to make those films. When I look back, I realize that I did manage to break through the clutter. It was a time of the Gadars and the Lagaans, and before that, there were the Sunny Deols, Guddu Dhanoas, Kuku Kohlis, David Dhawans. Then Karan Johar had made his debut, Aditya Chopra had made Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge, Sooraj Barjatya was the God. In that environment, I did make those films.

It is easier now. There is a system willing to listen to you. This system is willing to put its money into new writers. At that time, the system was completely resistant. For Jayate, we had nearly 150 previews to show to the distributors, and I remember distributors walking out of the theatre, quietly sneaking out and not coming back, or leaving without meeting me after the preview. And me desperately trying to call them, but nobody answering. It was a very, very dark phase, nobody even wanted to touch these films. The comment used to be “AREY YEH TO NFDC JAISE FILM HAI”. And NFDC was, at that time, the bastion of films that never got realized and nobody saw. (smiles)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.