By Rahul Desai

Notice some of the best male performances in Hindi cinema in 2018. Vineet Kumar Singh in Mukkabaaz, Ayushmann Khurrana in Andhadhun, Nawazuddin Siddiqui in Manto, Avinash Tiwary in Laila Majnu, Varun Dhawan in October, Gajraj Rao in Badhaai Ho. None of them, except Khurrana’s character, have grey shades. They are “protagonists” in the true sense – generally good guys whose battles are either internal or against the sociopolitical transgressions of a wider system. They can afford to position themselves as heroes: proverbial underdogs, passionate artists and lovers and athletes.

But what about the heroine? The pretty women who exist in context of the brave heroes – is there such a thing anymore? As long as India’s star-power culture is alive, there will be. But it isn’t quite the same: Deepika Padukone in Padmaavat, Jahnvi Kapoor in Dhadak, Sara Ali Khan in Kedarnath, Shraddha Kapoor in Batti Gul Meter Chalu, Tripti Dimri in Laila Majnu, Katrina Kaif in everything. They rarely top acting lists or inspire reels of feature space. The “popular” award categories are designed for them. The Madhuris, Sridevis, Kajols and Kareenas have already done whatever there is to do. Being a placeholder today is almost nostalgic, and not as novel as being a narrative device.

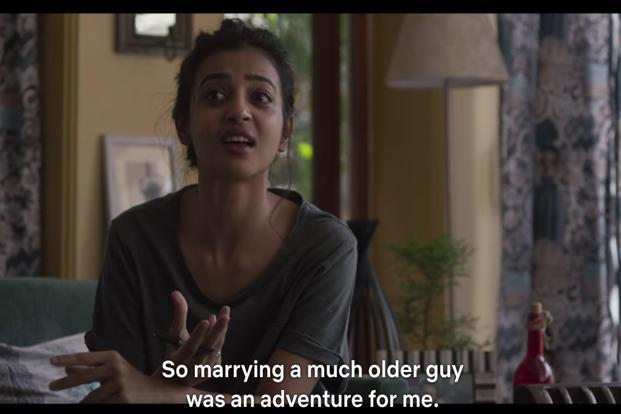

Note, in contrast, the five finest female performances of 2018. Alia Bhatt humanizes the cold-blooded spy in Raazi; Tabu frightens as a manipulative murderess in Andhadhun; Taapsee Pannu is the mercurial small-town heartbreaker in Manmarziyaan; Radhika Apte is a study of new-age morality as a delusional teacher intellectualizing her affair in Lust Stories; Anushka Sharma is hypnotic as the bloody-thirsty demon cursed with feelings in Pari. These characters are not the most agreeable human beings. Three of them are killers – of men, dogs, old ladies, but mostly men. The other two kill the idea of male agency – Manmarziyaan’s Rumi leaves in her indecisive wake the rubble of old-school romance, while Kalindi’s psychological toxicity in Lust Stories is destined to traumatize the boys she ensnares.

The Hindi film heroine has rebelled. In turn, the villain has disappeared. It’s hard to pinpoint the exact moment the pink ribbon snapped: I suspect it was somewhere between the frustrating traditionalism of the Bhansali epic, the adventures of Kangana Ranaut, the fading star of the Khans and the half-written Ranbir Kapoor heroines. You could also connect this trend to the reverberations of the #MeToo movement, the monetization of gender-inclusive storytelling, or the general democratization of commercial filmmaking.

The result is the “woman-oriented movie”: a term that, in most cases, is euphemism for the anti-heroine. The anti-heroine is, quite simply, the kind of girl that heroes’ mommas have nightmares about. She doesn’t have the time to be an underdog, athlete, artist, partner; love, too, only weakens her. Operating in a man’s world has made her complex, strong, wrong and unapologetically volatile. Inspired by Vidya Bagchi in Kahaani, you see Raazi’s Sehmat Khan and Andhadhun’s Simi go one step further and thrive on the “weaker sex” label. They exploit the preconceived notions of the male gaze. Nobody is conditioned to expect a pregnant lady, fragile teenager or bored housewife to drive the plot of life.

When they do turn out to be ruthless and clever and homicidal, the surprise experienced by the men around them is weaponized by the movies that occupy them. It is reflected in the surprise of the audience seeing these particular actresses, many of whom have spent a chunk of their careers playing the classic heroine, going grey – which only adds to our inverted perception of their performance.

Perhaps it isn’t surprising that it takes nothing less than a Hindi film actress to play the ‘bad girl’ today to arrest this nation’s attention. It took the horrific actions of bad boys to trigger our damsel-in-distress radars and view women as survivors. This is just them amplifying the language of survival. Even in applauding them, we are in fact judging them. An analogy lies in the situation of Neena Gupta’s Priyamvada in Badhaai Ho. She is invisible to the community as the timid 50-something woman conforming to the stereotypes of the aged heroine (obedient daughter-in-law, tender wife, indulgent mom) of the household. It isn’t until she exhibits a semblance of sexuality by getting pregnant that the world gasps in recognition. Nobody bothered when she spent her adulthood propping up her husband’s family, just like nobody bothers with the bland dutifulness of conventional heroines. Only when they transcend the plurality of Indian womanhood do they stand out. As cautionary tales. As individuals.

Some call it rebellion and others, living. Some call her the narrative device and others, the narrative. Heroines are a colourful manifestation of the movies, but anti-heroines are a sobering embodiment of life itself. The term “anti-heroine,” after all, is only euphemism for a woman.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.