By Priya Bhattacharji

The triangulated relationship of female sexuality, patriarchal control, and honour dates back to the era of Homer, the Mahabharata, and Ramayana. The sexual non-conformity of a woman and its subsequent threat to a community has existed as a trope across time and cultures.

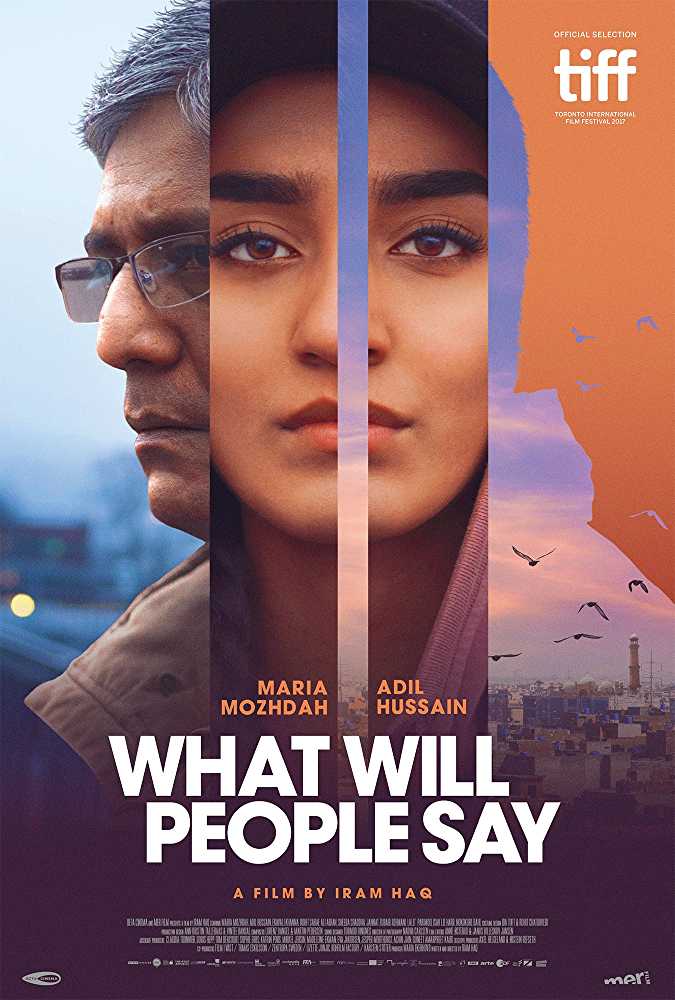

In Iram Haq’s Hva Vil Folk Si (“What will People say”?), the stigmatization of female desire is told through the turbulent story of a high school Pakistani girl raised in Norway.

The film, currently doing its rounds in the film festival circuit, stirs the long-standing issue of female sexuality and its potential danger to patriarchal social norms. With the wide-spread sharing of its trailer on social media, the film appears to have found an overwhelming resonance. Staying in a country with an embarrassingly high violence rate against women, the film hits a little too close to home. Through some brilliant casting and well-paced storyline, it powerfully narrates the aching tale of a teenage girl, struggling with cultural and societal norms.

Partially inspired by the Pakistani-Norwegian director’s life, the film invariably juxtaposes the ‘conservative’ East Vs the ‘liberal’ West to accentuate the tension. While stark cross-cultural differences form the crux of the film’s plot, the fear and control of female sexuality create a compelling sub-text.

The storyline is familiar: Nisha (played by Maria Mozdah), a lively and academically sound Pakistani, lives in Oslo with her parents. She appears to have been born and brought up in Oslo with little affiliation to her Pakistani roots.

During heated arguments, she’s reminded to be indebted to her parents for moving countries solely to provide her and her brother ‘a better future’. The only real cultural exposure to Pakistan is through food and music played at family get-togethers. Nevertheless, her brother and she, who’ve been long exposed to Western lifestyles, are expected to inculcate Pakistani values.

The real conflict of the film sets in when the father stumbles upon Nisha’s Norwegian boyfriend in her bedroom (in his house). His territorial instincts grant him the right to assault and abuse the boyfriend. The fear of a defiled daughter and a soiled reputation in society lingers heavily on the entire family.

The “Log kya kehenge?” (What will people say?) syndrome kicks into play, for the need for collective acceptance precedes individual turmoil. With the intent of rejuvenating Nisha’s sense of morality and tradition, she’s packed off to Pakistan with coercion. The father is convinced that leaving his daughter in the disciplined care of unfamiliar relatives and customs will purify her.

Nisha’s journey of suppression and subordination is hardly sublime. The reining in of cultural oppression is formidable, one that drastically changes her dancing, grinding Oslo high-schooler ways. With some resistance, she finally accepts her fate of a fully clad all-girls school-goer in Pakistan, domesticated and demure.

Through Nisha’s family, the nexus of patriarchal control is made recognizable. The extremely society-conscious mother and aunt, who regularly (and sanctimoniously) chip in with ‘log kya kehenge?’, serve as a reminder that patriarchy has no gender. The father (played by Adil Hussain) indulges in the role of protector for the family as well as the preserver of tradition. The brother is shown being raised in his father’s shadow.

What’s remarkable about the film that it does not excessively vilify or victimize any character. ‘Log kya kahenge?’ is the unconscious control mechanism, while ‘kya muh dikhayenge?’ (how will we face society?) is the ultimate threat to Nisha’s family. While they regard her sexuality as a source of ignominy, the film displays the problematic power dynamics inherent in a patriarchal society. With a palpable sense of turmoil and chaos looming throughout the film, Haq picks on the unbearable rigidity of these norms.

From male aggression to female nit-picking, everyone’s coping and struggling to live up to its dictates. The daughter is torn between expectations and individual desires that brew mild rebellion. The father is torn between ‘what’s best for his daughter’ and his own emotional attachment to her that leaves him bewildered. The manner in which personal anguish is repeatedly squished by societal norms questions the purpose of moralism and tradition.

The superficial notion of ‘marriage’ prevalent is laid out in tragicomic ways. The first time Nisha is found with her boyfriend, her family is ready to accept her if she marries him. The second time, Nisha finds love with her first cousin. Not only is their love denigrated by the police, the family is convinced it is Nisha’s worrying sexual appetite that’s corrupted the boy. Again, marriage is suggested as the swiftest cover-up. The third time, Nisha’s family tries to settle her down with a ‘well-placed’ boy to alleviate from her ominousness. In Nisha’s milieu, marriage is a ‘rational’ transaction with little concern for individual desires.

In the end, Nisha, an ambitious individual, a loving daughter and sister, becomes a mere object of exchange to invalidate her disgraced position in society.

What’s heart-wrenching is that Nisha’s human value diminishes as the film progresses. From an individual with unlocked potential, she is reduced merely to a site of honour which the family is dedicated to upholding at any cost.

Nowhere are her desires or needs considered, except for one fleeting moment when her cousin (who later turns into a love interest) asks her if she likes paan or not. This story of subjugation reminds us these problems aren’t specific to Pakistan, but to any society where ‘what will people say’ precedes ‘what an individual wants’.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.