By Pranav Joshi

There is an inherent dichotomy to Indian historical folklore and the myths they give rise to. Tales of bravery, virtue and sacrifice infused with the magical, enigmatic nature of antiquity command a subliminal pull over listeners across generations. For these are admired as gateways to a heightened reality where man can either embrace his divine, civilized character or give in to primal, self-destructive urges to annihilate the forces of good. And it is this shared culture of recognising the perennial struggles we have been plagued with over the ages, in different forms and contexts, that enable us to embrace legends that transcend our flimsy bond with reality.

The medium of film, with its infinite capacity for visual splendour and pure immersion, affords the means to reconstruct, consummately explore and establish these worlds lost in time by giving flight to the creativity of their authors. Though the opportunities to infuse wonder in historical re-imagination are manifold, grounding it in substantial dramatic conflict helps in making it accessible and simultaneously thought-provoking. Yet a formula arises in place of erstwhile innovation which imports the lore and the legends as they are, but nuance and depth are lost to ostentation. It can be argued that the established grammar of grand historical dramas in Bollywood inhibits a thorough exploration of the ideologies, fears, vulnerabilities and concerns which are hidden behind veils of allegory and cryptic verse or prose. While the occasional deviations from historical accuracy are often condoned as a staple approach to make engrossing cinema, a patent disregard for the quotidian aspects of the past also does not necessarily deprive a film of its potential lustre.

Taking seminal period dramas like Mughal-e-Azam and Pakeezah as precedents of the larger-than-life form of mounting these stories, the films can hardly aspire to contain factual truth. Yet, they eschew rigorous, almost pedantic adherence to fact and theory to offer something more profound – the ostentatious, sophisticated yet emotionally rich and astute experience of an imagined history during the Islamic period of rule. Characters like Madhubala’s Anarkali or Meena Kumari’s Sahibjaan do not merely embody virtue and integrity as part of an alien tapestry of affected identity. The stark truths of the world they perceive, especially its inequalities and prejudices, emboldens them to seek their own fate, or at least be self-aware enough to rise to the occasion and become a poignant portrait of human endeavour.

In a fairly recent, equally politicized fictional depiction of arguably the most famous Mughal emperor Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar, director Ashutosh Gowariker wove a fairly straightforward narrative filled with messages of goodwill – tolerance, love, the power of honesty and the eventual triumph of good over evil. Where the film lacks in complexity though, it more than makes up in its dignified adherence to movement and rhythm and is powered by incredible cinematography, precisely in the depiction of its songs. The epic then, becomes the musical form and the story of an inherently just king who learns to rules over subjects with equanimity becomes archetypal and is treated as a necessary contrivance to sustain the illusion of the benevolent, all-inclusive myth.

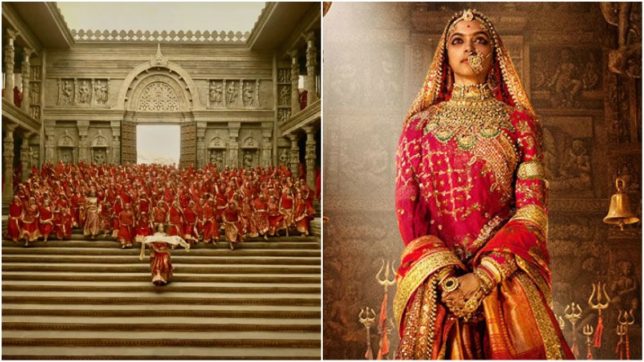

Bhansali’s Padmaavat, the most recent and controversial attempt of re-inforcing the cinematic myth, adapts Malik Muhammad Jayasi’s 16th Century poem, which owes its philosophy of fatalistic obsession and hedonism to Sufism, translates it on screen just in letter, not in spirit. The premise is followed closely – Padmavati (Padukone) is a warrior princess from the enchanted Buddhist land of Singhal who falls in love with the stoic Raja Ratan Singh (Kapoor) and accompanies him back to his kingdom Mewar. A courtier banished by Ratan Singh soon reaches the palace of the Delhi Sultanate ruler Alauddin Khilji (Ranveer Singh) and enthrals the debauched, power-hungry king with tales of Padmavati’s beguiling beauty. With no way to mollify his raging desire and obsession, Khilji lays siege to Mewar, defeats Ratan Singh and his army only to find that Padmavati, along with the women of the palace, have committed Jauhar (mass immolation), thereby choosing death over dishonour. The film on the other hand, in its quest for resolution, ignores the power of the epic and lets the underlying complexities – Rani Padmini’s tragic decision and Khilji’s obsession with equating absolute, material beauty with power and knowledge – subsume within the pre-occupations with grandiosity.

A Persian couplet’s intricate calligraphy itself seldom evokes the lyricism and profundity residing in its expression. Similarly, Padmaavat consciously ignores the need for subtext even while it carries on with the mythical dimensions of its plodding narrative and becomes a banal costume drama. With the characters played by the three protagonists being reduced to shallow personifications of the overt themes arising from the poem, the film simply ends up being a hokey and banal translator, not an enhanced transcreation, expanding the horizons of historical fiction. The potency of the material is also partly stifled by a refusal to acknowledge the multi-faceted, daunting and ambiguous nature of evil and the treatment of the antagonist betrays hesitation on part of the filmmaker to capture the real essence of the poem. Ranveer Singh, in treating Khilji’s lack of scruples and behavioural decadence as neurotic, self-absorbed eccentricity, also seeks to further downplay the raw terror of the character’s ruthlessness and completely detaches it from the psychological reality of the Faustian path he wilfully treads on. While Ratan Singh is depicted as an obdurately principled man, the flagrant shortcomings of his character are hardly lent any empathy, almost as if his doomed fate does not warrant a more earnest exploration of his psyche.

A faint glimmer of light is provided by Jim Sarbh’s perceptive, intimate portrayal of Khilji’s eunuch slave and army general Malik Kafur. Cloaking their relationship in enigma, Sarbh’s Kafur appears to be as outlandishly demented as his master. Yet his covert assertion of his identity and orientation manifests in the way he panders to Khilji’s whims, normalizing the latter’s erratic deliriums in the process and unconditionally extending solidarity when the need arises.

The biggest blow to the film’s credibility and intent comes from the portrayal of Padmavati herself. The blandness of her love story coupled with attenuated dramatic presence and impact reduce her to mere emblematic illustration. Apart from a bravely mounted rescue of her husband, her vitality is undermined to vicariously indulge Khilji’s outlandish notions of sensuality and this critically suppresses the intended impact of the overall tragedy. Being an operatic filmmaker whose bold, painted strokes of melodrama populate richly composed frames, the director, through Padmaavat, seeks to establish himself as a contemporary thespian of historical fiction on film, enriching the medium with the lavishness of his magnum opuses. Yet a repetition of style and a lacuna of cinematic invention hampers his vision to the extent that a certain song ‘Khalbali’ adds little to the proceedings and feels like an insipid rehash of the war-mongering victory cry of Bajirao’s ‘Malhari’, although bereft of the latter’s emotional alacrity. An episodic, humdrum structure also ends up borrowing significant time until the final act, rather than evoking the proverbial ‘calm before the storm’.

The cataclysmic event of Jauhar, unfortunately the mainstay of the film, is also not the eerie, angst-ridden wail of hopelessness it intended to be. The violent defeat and sorrowful demise of Ratan Singh, shot with a certain fluidity uncommon in Bollywood for the titular battle between good and evil, results in an emboldened Khilji rushing to the gates of Chittor. What strains credulity here is that a man feared as nothing less than a demon on Earth, who has no compunction for his blasphemy, cowers in fear at the sight of veiled women screaming ‘Jai Bhavani’ and advancing with hot coal to drive him out. Padmavati, having coldly declared her desire to commit Jauhar in the presence of her now deceased husband, addresses a group of women so perfunctorily that the women’s tacit assent to commit the horrific act shatters the film’s illusory authenticity beyond repair. Bhansali here, along with cinematographer Sudeep Chatterjee, prefer to visually overwhelm by showing groups of women marching on in slow motion, to an ear-splitting background score. Deathly silence and its soul-crushing, nightmarish effects are glumly traded for bombast, almost distancing the viewer from the sheer helplessness and misery of fighting the instinct to survive.

Moulded as an ode to Rajput honour and grit in a token voiceover, the film not only fails to do justice to the medieval social mores which might have informed Jayasi’s poem, nor does it act as a testament to the vigour of stories which stand the test of time. Where it should have burned with fiery indignation and sorrow, it only proffers dying embers, existing in the mere shadow of a legend it could have been.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.