The fact that Vishal Bhardwaj has a special relationship with Shakespeare is well-known. He has made three films based on the plays written by Shakespeare—Maqbool (based on Macbeth), Omkara (based on Othello), and Haider (based on Hamlet). The strong leading women characters in the three films, namely Nimmi (Tabu), Dolly (Kareena Kapoor), and Ghazala (Tabu), are uniquely compelling in their own way. There is a kind of perceived duality in his female characters, and Bhardwaj uses certain symbolic elements, particularly in Omkara and Haider, to accentuate their mysticism and enigma.

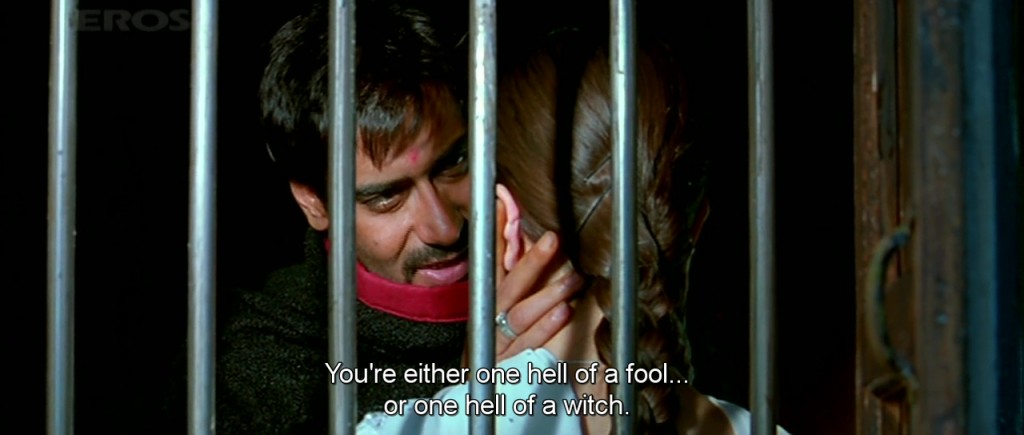

In the early moments of Omkara, there is a scene where Omkara (Ajay Devgn) is walking towards Dolly. Raghunath Mishra (Kamal Tiwari), Dolly’s father, comes in his way, and tells him, “Bahubali, aurat ke tariya charitra ko mat bhulna. Jo ladki apne baap ko thag sakti hai, woh kisi aur ki sagi kya hogi.” The film’s script as well as the subtitles translate this as, “May you never forget the two-faced monster a woman is. She who can dupe her own father will never be anyone’s to claim.” It is noteworthy that ‘two-faced monster’ is used to describe Dolly. When Raghunath says this, he is looking at Dolly, who is seen standing behind the tinted glass of his car. Just like Raghunath comes in the way of Dolly and Omkara in the scene, the same words would later come in the way of Omkara’s ability to trust Dolly. Dolly’s father germinated the idea of her untrustworthiness in Omkara’s mind at that moment. Omkara will later look at Dolly through the tinted views of her father. He would see two faces of Dolly, and is not sure which one is her true one—the one that loves him, or the one that is having an affair with Kesu (Vivek Oberoi) behind his back. In fact, at a later point in the film, Omkara jokes about the two faces of Dolly when he tells her, “Ya toh tu bahut badi lool hai ya bahut badi chudail.” Whenever he looks at her, there is a thought that crosses his mind that either she is a fool to fall in love with a man like him, or she is a witch who does black magic beneath the veneer of her beauty. When Omkara kills Dolly, he says the same words, “Tariya charitra.“

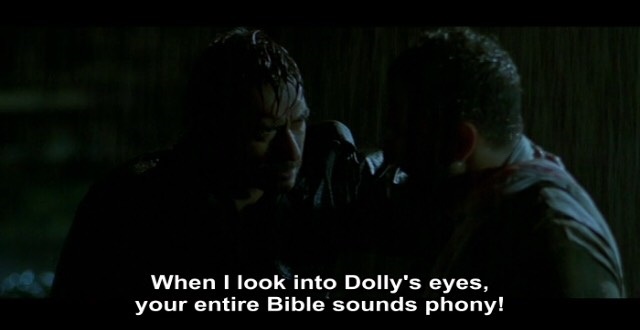

In addition, we see that Dolly’s father uses the word thag to describe her. Thag means to deceive or to dupe someone. This thagna is also used in the song Naina Thag Lenge where the lyrics say that one must never trust his eyes, as they will eventually con him. Looks are often deceptive, and what appears to be true is quite different from what is actually true. At a later stage in the film, Omkara questions Langda (Saif Ali Khan) on the verisimilitude of his account of Dolly’s relationship with Kesu. He is suspicious that whatever Langda tells him about the stories of Kesu and Dolly, there is never any third person present to validate Langda’s words. He feels doubtful of Langda because whenever he looks into Dolly’s eyes, he only sees the love for him and Langda’s account of Dolly and Kesu’s affair sounds crooked to him. Teri saari Ramayan kapat lage hai mujhe. Langda plays his cards and manipulates people to convince Omkara of Dolly’s infidelity. Omkara was, thus, unable trust the love that he saw for him in Dolly’s eyes, and kills her because one must never trust the eyes as naina thag lenge.

Vishal Bhardwaj effectively uses a swing as the symbolic representation of the two faces of Dolly, or more aptly, the two shifting faces of Dolly in Omkara’s mind. There is many a scene in the film where Dolly is often found sitting on a swing. After Omkara is angry with Kesu for his violent outburst after getting drunk at a party, Kesu asks Dolly to talk to Omkara for his forgiveness. In the particular scene, Dolly, dressed in pure white, is seen on the swing outside, with Indu on one side and Kesu on the other side. She is happily enjoying herself on the swing, and tells Kesu that she will talk to Omkara so that he can forgive Kesu. In the song Lakad Jal Ke, we see that Dolly, dressed in white, is sitting on a swing again and Omkara is standing beside and watching her. The camera pans the entire view when Dolly is circling on the swing. The lyrics of the song imply Omkara’s jealousy and suspicion. Lakad jalke koyla hoye jaaye, koyla hoye jaaye khaak. Jiya jale toh kuch na hoye re. Wood burns and turns into coal, the coal turns into ashes. When the heart burns, nothing happens. The burning of Omkara’s heart led to killing the very person he dearly loved.

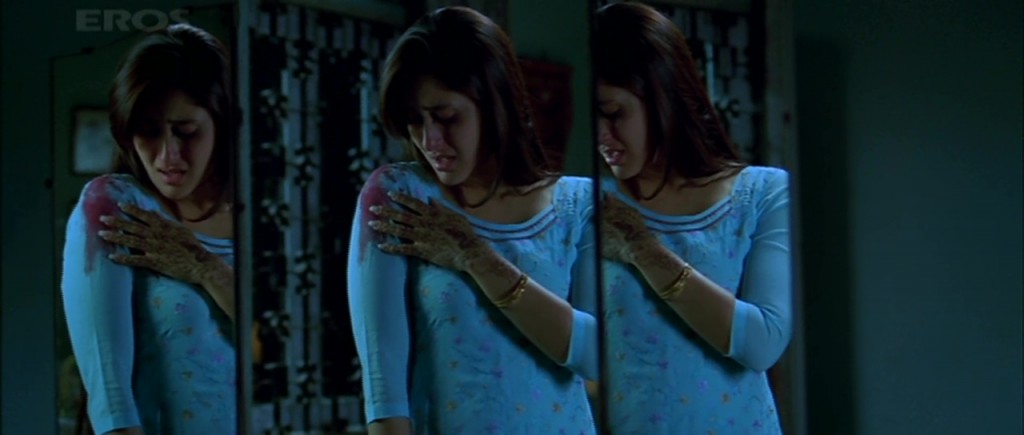

At a later point, we again see Dolly and Omkara lying next to each other on the swing inside Omkara’s house after a night of passionate lovemaking. Dolly is dressed in black and white, while Omkara has his black shawl with the red border draped over his body, and the swing is red. Omkara caresses her and sings a lullaby to her, whose words say that he makes an unbreakable promise, like King Dashratha’s, if she wakes up. Dolly opens her eyes, and asks for Kesu’s forgiveness. Hearing this, Omkara storms out of the room. The same scene is repeated in the last moments of the film where it takes a much sinister turn, making it one of the most hauntingly memorable endings in films. It is the night after the wedding of Dolly and Omkara. They are again lying on the same swing as before. Dolly is dressed in her bridal red saree and makeup, while Omkara is wearing white. Now convinced of Dolly’s infidelity, Omkara puts a cushion on Dolly’s face and suffocates her to death. However, only minutes later, he gets to know the truth from Indu (Konkona Sensharma). Realizing his monumental crime, he starts singing the same lullaby, which he sang earlier, to wake her up, but this time, his Misri Ki Pudia will never wake up again. Consumed by guilt, he shoots himself and dies. Dolly’s dead body remains swinging on the swing, and Omkara’s dead body is seen below her on the floor. The film ends with the shot of the two dead bodies and the unforgettable sound of the creaking swing, in a way, signifying that Omkara’s emotional upheaval, swinging and seesawing between trusting and doubting Dolly, eventually, led to the end of their story. The swing, where Omkara sang a lullaby for Dolly’s innocence, like that of a little child, becomes the deathbed for Dolly’s lies and manipulation, like that of a shrewd woman.

There is another swing-related scene in the film where Dolly and Omkara of them are lying in the swing, and he tells her his life story, and the reason as to why he is known as a half-caste in the village. She replies that even if the crescent moon is half, it is still called as the moon. The swing is their area, and shifts from being a place of trust to being a place of suspicion. It must also be said that the color palette of the above-mentioned swing scenes. Dolly and Omkara are dressed in white, red, and black, the colors that represent emotions, such as love, purity, doubt, and manipulation, among others.

Many notable film scholars have elaborated on the motif of the swing in the film with other interesting interpretations. In Singing to Shakespeare in Omkara, Poonam Trivedi writes, “With the dead lovers laid out on and below a swing, its visual underlines what the song hauntingly echoes—the tragic swings of fate.” In Deconstructing the Stereotype: Reconsidering Indian Culture, Literature and Cinema, Kaustav Chakraborty writes, “The fact that the bed is depicted as a swing invokes the interchangeability of child-like vulnerability and sensuality, and the oscillating attitude that her lover shares toward her, as father-figure/protector and killer.” In Constrained Women in Omkara: Marriage, Mythology, and Movies, Rebecca Dmello observes a caste subtext in the swing and opines, “In Omkara, however, there is a deliberate and intriguing physical disconnection of the two main characters. On some level, the spatial disorientation is enhanced by a swing in motion. The separation through the use of the swing also has a pronounced effect in representing the disparity between the castes of the two characters. Dolly, who is a Brahmin, is elevated even in death while her halfcaste husband languishes below her. Bringing the caste disparity to the fore in the last scene, Bhardwaj highlights the suppression experienced due to the insecurity that arises as a result of the caste system.“

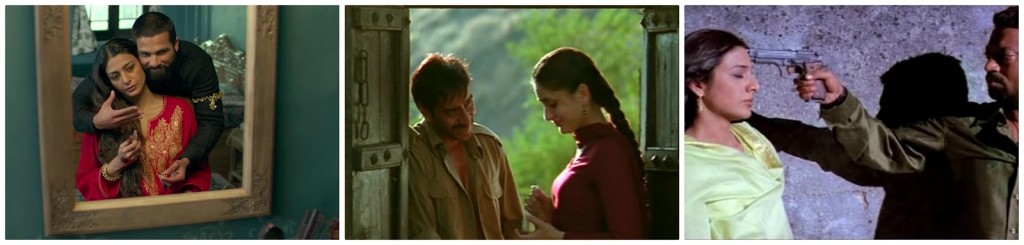

Vishal Bhardwaj makes a similar comparison of this perceived duality of the woman in Haider as well. Like the two faces of Dolly in Omkara, Ghazala was also shown to have two faces. At one point in the film, Ghazala walks into her old house that was destroyed by the Indian Army to meet her son Haider (Shahid Kapoor). When she enters the house, there is a broken mirror on the wall, and in that mirror, we can see two faces of her. On seeing her mother, Haider remarks, “Do chehre hain aapke. Yeh baayein vala masoom hai, ye daayein vala chor” She has two faces literally in the scene, and metaphorically in the film. There is something mysterious about Ghazala that throughout the film we are not sure whether she was complicit in the murder of her husband or was she only a victim. In the beginning of the film, she is teaching a poem on house—What is a home? It is brothers and sisters, and fathers and mothers, it is unselfishly acts (sic) and kindly sharing, and showing your loved ones you are always caring—perhaps, pointing to the unhappiness in her marriage because her husband was always busy and she said that had no wajood in his life, so, sometimes, we wonder if she was a victim as well. We also see that she is sleeping in the same bed with Khurram, and we wonder if she did something terrible, too.

At an earlier stage in the film, Haider comes back from Aligarh and goes to his uncle’s house and he stands behind a translucent purdah listening to the conversation between Ghazala and Khurram. The purdah was what defined Ghazala’s mysticism, that we cannot see her clearly. There is something hidden and enigmatic about her, like the view from a purdah. There are quite a few scenes in Omkara as well where Dolly is seen behind the purdah, reflecting Omkara’s cloudy vision. However, the difference between the two faces of Ghazala and Dolly is that the audience is well aware of Dolly’s innocence all along and the viewer knows that it is Langda’s manipulations that are pumping doubts in Omkara’s mind (there is literally a hand pump scene in the film where Langda keeps instigating Omkara about Dolly while taking out water from a hand pump), while in the case of Ghazala, it is not only Haider, but even the audience is not able to fully make up its mind about her character till the end. As Ghazala says, “Kuch bhi kar lun, villain to main hi rehne vali hun.” Whatever she does, she is going to be called the villain.

Curtains in Omkara and Haider

We don’t see an explicit mention of the two faces of Nimmi in Maqbool. But there are shades of duality in her character, too, as Baradwaj Rangan eloquently puts it here, “When Abbaji begins to shower attention on another coquette, when Nimmi realises her days as mistress are numbered, she garlands herself, like a sacrificial goat, and asks Maqbool to kill her—or kill Abbaji. At times like these, it’s difficult to discern if Nimmi truly loves Maqbool, or if he is, to her, merely a weak-willed instrument of redemption.”

Even though Vishal Bhardwaj takes the material from the Bard, he adapts them to an Indian setting with a realism and a rootedness. It never feels fake. The combination of the elements of the Bard and B(h)ardwaj, Hindi cinema’s Bard, make these three films as some of the finest films of all time in Hindi cinema, and its characters, especially, the women, as some of the most memorable ones.

Books In Movies:

Godaan by Munshi Premchand

Book Recommendation:

Shakespeare’s Othello because a post on Shakespeare will be incomplete without mentioning his writing.

Other Reading:

1. On Haider—Link

2. On Omkara‘s script—Link

3. On the Sacred and the Profane in Omkara—Link

4. On the Constrained Women in Omkara: Marriage, Mythology, and Movies—Link

Dialogue of the Day:

“Chaand jab aadha ho jaave hai na, toh bhi chaand hi kehlave hai.”

—Dolly, Omkara

[You can read more of the author’s work on his blog here]

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.