By Pranav Joshi

Director: Navjot Gulati

Rating: 3/5

Balcony views, square areas, negotiating middlemen, capricious buyers – a common sight across Mumbai’s hysterical real estate market. It is a world which is said to grant utmost mobility to the aspiring middle class, provided they have the bank balance and the required status to crown themselves as proud owners of “signature residences”. In this material realm, money supposedly is not the only stepping stone to the keys of a brand-new apartment – furnished or non-furnished.

Acceptance by nosy neighbours, towering society secretaries and all-seeing, ever-wise, retired residents is as crucial as meeting the deadline for the next monthly instalment. Only, the former entails no passage through countless “agniparikshas” of social conformity. In a city which allegedly thrives on the dichotomous relationship of anonymity and indifference, reports often spread like wildfire of deliberate prejudice or xenophobia – even in cosmopolitan, seemingly progressive localities. The media professional being denied a rented flat because he is a Muslim, a young 20-something IT engineer in a housing society being forced to appear before a presumptuous, parochial de-facto court of permanent society members because she dared to call her male colleagues to her house for a birthday celebration – front page news in the local papers reminiscent of the cracks in Mumbai’s glass façade of being “maximum city”.

What leads to this unbridled state of near repulsion, enough to deny a diligent tenant his home? Those in defence of such unnerving practices claim the right to control who does and does not stay in their vicinity. They say that the walls separating flats are not enough to ensure that breaches in social norms do not walk into their own doorstep.

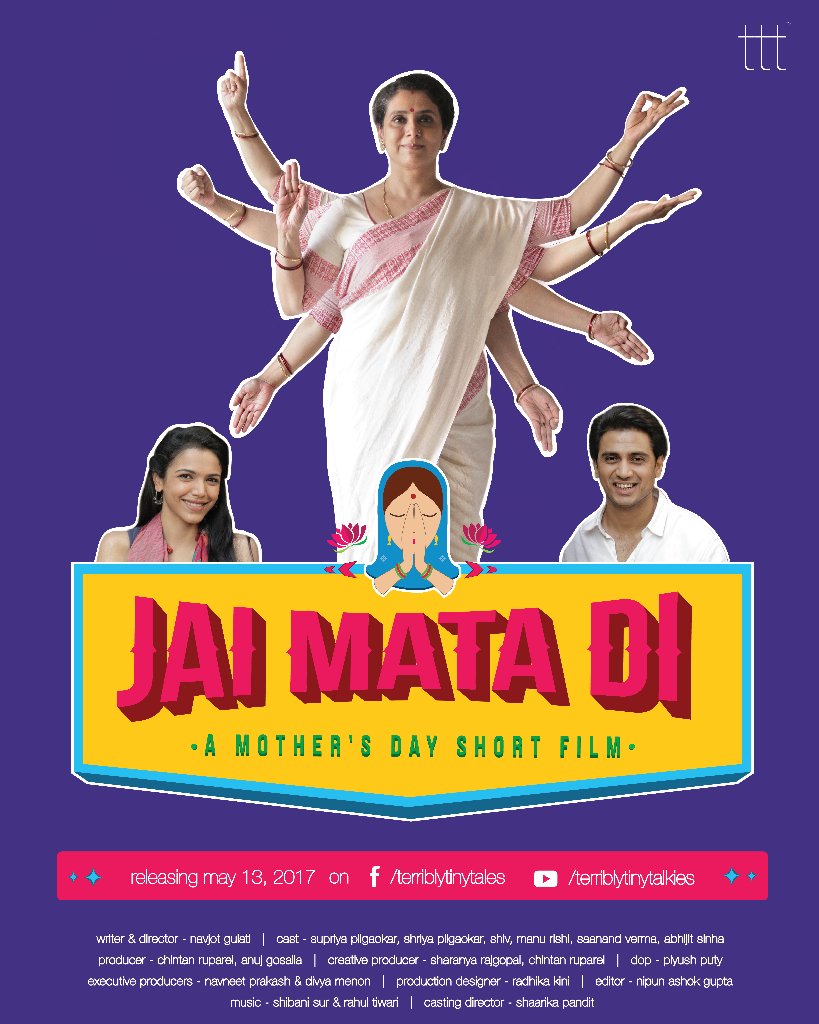

Jai Mata Di, Terribly Tiny Talkies’ latest short film offering, does not preach the ambition to break down these walls of conformity. Rather, it advocates just walking through them, with the cloak of smugness and invisibility. Navjot Gulati’s film rather cheekily confronts social mores by circumventing their vile manifestations using fraudulent identities and incredulous powers of persuasion. Shiv Pandit and Shriya Pilgaonkar play the average, unmarried couple hunting for the perfect house to begin a serious phase of their deepening relationship. A broker (Saanand Verma, adhering to type) is eager to clinch a deal as he advertises the lack of meddlesome neighbours and an abundance of pristine views from an nth floor flat. Sensing the amicable mood of his clients, the broker warns them of possible confrontations with the society secretary (Manu Rishi) and his officious ways of ensuring that his residential complex is free of unmarried couples and bachelors.

The film hinges on the couple’s pursuits in acquiring a flat they have set their sights on. While Rishi creditably humanizes his character as the nosy, conventional low-level bureaucrat deciding the suitability of flat buyers and tenants, the climactic scenes he shares with the couple call for abnormal degrees of disbelief. Unthinkably masquerading as brother and sister, the couple brings their alleged mother to furnish a non-existent familial bond in the eyes of prying residents. The secretary inexplicably buys their story and admires their mother’s culturally sound outlook.

Played with great vibrancy and wit by Supriya Pilgaonkar, her character is the major catalyst lending this film a certain relevance beyond cursory nods to liberalism. She is neither the voice of compromise or open hostility to a regressive mindset, but the closest impersonator of the voice of pseudo-pragmatism – the benevolent opportunist. In the context of her occupation, the title of the film evokes the abstract, all-pervading geniality of “Mata” – slyly deviant from all the excessive religiosity but still an outlet of relief for vexed people leading ordinary lives.

As the film reveals her penchant for appropriating motherhood across communities for young, harrowed couples in similar situations, one cannot help but think that the freedom afforded to her through the anonymity she wields is a fantasy. She ultimately weaponizes it as a service which, in reality is a necessary mirage for many millennials today, who need to keep up façade after façade merely to ensure they don’t lose their homes lest they defy authoritarian invasions into their privacy.

Watch film here:

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.