By Pranav Joshi

Human imagination can be interpreted as the boundless manifestation of intellect. A profundity bearing an ingrained sense of the self, anchored in a shifting world. Cinema generally seeks to define the contours of this thoughtfulness and its emotional impact.

The horror genre in film, on the other hand, specifically toys with the perception of fear. Fear, it can be argued, first and foremost negates our sense of security — robbing us of our desire to exercise absolute control on our senses. An unexplained voice, a shadow in the dark, a memory you never knew existed or even somebody’s unnerving company can poison the lulling sense of safety. Such is the mind that it can conjure the most hideous monsters emerging out of swaying hedges or eerie, calm lakes.

If for a moment we dissociate ourselves from the psyche of self-preservation, the very act of experiencing fear seems to be a gateway to a heightened sense of reality. What if our spectres, spirits, demons and banshees wanted just that? To force us to seek what lies beyond, even if the path is ridden with nightmares or sadness? But we cannot possibly make that irreconcilable agreement, because we say the premise is evil. For it would mean that our mortality mattered no more. And that is something we cannot deal with since we cling to life and hope for fate to turn our fortunes.

What then is the function of a true horror story? Film after film just resorts to elevating heart rates with contrived shocks and scares, using mere distractions while taking refuge in shallow myths and archetypes. They seldom delve deep into how these nightmares get a life of their own because they seek to stupefy and not truly unnerve their audiences. Cinema has the potential to evoke dreams residing in the deepest abyss of fear as it penetrates into fragile, emotional troughs — killing joy, love and empathy.

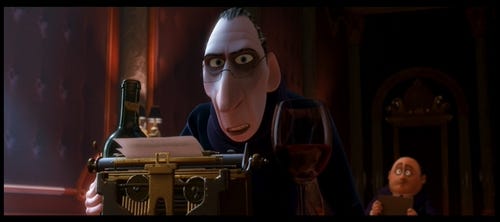

The uncertainty of facing inner or external horror is beguiling in itself – bringing out either the best or the worst of us. Jack Torrance, from The Shining (1980), lost his battle with sanity as his conscience choked in the pernicious, isolating atmosphere of the Overlook Hotel. Rosemary, from Rosemary’s Baby (1968), has a more complex journey, navigating the perils of motherhood and choice, while challenging her sense of reality with evil at her very doorstep. The VVitch (2015) on the other hand is a vivid, vociferous cry for the inevitable death of human compassion when grappled by forces beyond time and form. While some films dare to reveal shrouded echoes of psychological instability, others draw upon external agents of sorrow, angst and even violent retribution. Stories of revenge-seeking souls abound in Japanese folklore, mainly of wronged women returning as the undead to exercise judgement on heartless, abusive husbands, looking at patriarchy with utter disdain. Kwaidan (1964) delves into myths firmly entrenched in the supernatural by evoking dread and despair at the dysfunctional aspects of Japanese society.

The paranormal world’s essence is thus more than shapeless whispers dousing candles in dark, shadowy hallways. Its diabolical energy has never ever been chained just to the creaky door or the rattling window. Nor does it reside only in a possessed girl screaming at the top of her lungs for escape. Instead, it rears its head up when we long to escape torture, denying us relief and provoking our beastly nature. It lends an unprecedented glimpse into crevices where even reason falls victim to timidity and disorientation. Like all other worlds we relentlessly find confounding, it prompts us to ask unsettling questions. But one question we should avoid is, “Who made that noise on the table across the hallway?” The answer to that question cannot resolve the intangible sense of foreboding. It will merely establish boundaries of shape, voice and origin.

Instead, we can ask, “Are my senses more than mere conduits of survival?”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.