By TANUL THAKUR (@Plebeian42)

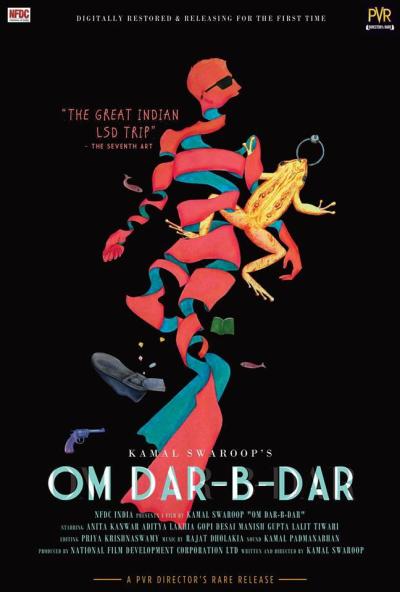

For a movie to truly befuddle you right from the outset, it has to usually play with one of the three elements in its arsenal— the film’s world, its inhabitants or the structure. If you end up tweaking or distorting one of those three elements considerably, you have a film, which has a mind of its own. But Om Dar-B-Dar manages to delight and endlessly frustrate you even while, for the most part, keeping all its three elements sane. To begin with, the film’s world isn’t unhinged, soaked in fantasy; it’s set in Ajmer. Moreover, neither are its characters aberrantly whimsical nor does it toy with the idea of time so much that it becomes difficult to keep track. So what really makes Om Dar-B-Dar so loony? Loony enough that it has become the film, especially over the last few years— finding its way into cinephiles’ laptops through peer-to-peer sharing to cultivate a shared understanding of what is it actually about.

Any film, whose primary strength lies in being esoteric should accomplish something right at the outset— its ability to intrigue. If you think about it, it’s quite fascinating. You don’t clearly understand what’s going on, but you can’t take your eyes off the screen either. You keep running around in circles, frustrated yet fascinated, tired yet not wanting to give up. The first half of Om Dar-B-Dar had a similar effect on me. And for a reason. Because for the first 50-odd minutes or so, most of the film’s frames are packed with contradictory, conflicting elements. For instance, at a get-together on a terrace, the conversation about a man landing on moon is soon taken over by a conversation centred on archaic, silly religious customs. It’s this tug of war—between the progressive and the regressive, between the future and the past, between the logic and the faith—that Swaroop most excels in. It’s this dichotomy that informs most of the film’s first half.

Similarly, many of the scenes are pulled apart by two different forces, giving the film a certain strained texture. In many scenes, the audio is divorced from the video making us aware of a singular relationship between the two, and what it means for two disparate things to co-exist. For instance, the radio announces about the imminent moon landing while the camera contrastingly lingers on the mosques and temples, giving rise to a unique heady concoction. But it’s hardly a rule that binds the film. In fact, the film is unfettered, constantly jumping hoops with irreverence. So if one scene is a queer juxtaposition of science and mythology, the other scene is about women emancipation— the female characters cogitate more than once whether women can go to Everest; the distinction between being free and independent. And as if these untied, unrelated threads were not unruly enough, the film also talks about the hegemony of the rich and the shame that’s associated with being a lower— either caste wise, or financially. It’s a mad chicken race, all right, but it doesn’t exasperate you. In fact, some of the scenes are so oddball and bizarre—especially the one where a character address Rajiv Gandhi as Raju and exhorts him to ban googly in cricket—that you welcome their stay. Or, the one where an eager, sexually aroused Jagadish (Lalit Tiwari) is moments away from fornicating but can’t seem to untie his pajama’s strings. These scenes keep the film real, make it rooted, while the subsequent scenes keep pulling it away to fantastical realms. It’s difficult to not be enchanted by the constant confluence of extremes.

However, the film changes its course considerably in the second half— not only does it become increasingly dream-like, but also abandons lampooning us the way we are: one step chained to tradition while the other itching to leap forward. It also become a little uninteresting, although, here too, Swaroop keeps overwhelming us with difficult-to-fathom images, but they appear progressively unhinged. This portion of the film perhaps needed another element to keep it continuously intriguing—and I precisely cannot pinpoint what—maybe the oddball humour or the clever juxtaposition. All of that is missing here, and it might have been intentional to make the film increasingly dark—a nod to loss of innocence—but it doesn’t quite aid the film. Also the film moves from Jagdish’s story to Om’s story quite haphazardly and concentrates solely on the latter’s for the much of its second half. And given the second half’s entirely inebriated, divergent nature, you are always at a distance from Om.

In the case of abstract movies, I, as a viewer, am not primarily fixated on knowing what the movie is about—as long as it engages me enough via the mini-films in it—but I definitely want to be sucked in enough to want to know what is it about. Much like the exuberance of youth this film points to, as indicated by its title, the film itself is restless, and while most of the times you would want to keep running alongside it because you want to keep the conversation going; after a point you just become exhausted and stop catching up. The film was, anyway, running a different race.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.