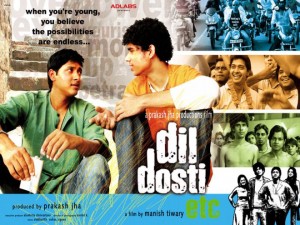

Pawan Sony, the ‘specialist’ screenwriter behind some of the more interesting titles in Bollywood over the last decade (Dil Dosti Etc, Sixteen) is a journeyman. He focuses solely on cinema, and has become the go-t0 man for quite a few directors who need the right person to pen down their ideas.

Here, CHINTAN BHATT speaks to him about his early days, Dil Dosti Etc, Sixteen and the changing landscape of the Hindi film industry.

Can you tell me a bit about your background before films?

PS: Writing is the only thing I wanted to do ever since I can remember. I started off in Delhi — first as a journalist, then as a documentary writer/maker. And in 2004, I decided to move to Bombay to pursue a serious screenwriting career.

How did Dil Dosti Etc happen?

Manish Tiwary, the director, had posted an ad looking for writers on a mailing list (the internet was relatively new back then) called webcinema.org. He used to work with the United Nations, and was based in Rome. He would visit India quite often, and was thinking of leaving his job and getting into filmmaking. I met him, we gelled well together. Dil Dosti went through quite a transformation; it started off with an entirely different idea from what it turned into. The story just evolved over those three years.

How do you mean “different”?

The basic idea was to make a film about a personal journey set against a Mandal Commission protests that had happened in the early ’90s. The characters, story and background were different. We worked on 3 or 4 drafts, but we were not too happy with the politics of it. So we changed it and made it into a more accessible story about a wager between the two young protagonists winning college presidential elections and sleeping with three women in a day.

So it eventually became a mishmash of who you are and what you want to make? The film comes across like that, where you’re still trying to find a voice with that brand of humour. It gained quite a cult following later…

Not really. A lot of it came from our own experience. We were from Delhi University; it wasn’t quite an autobiographical film (smiles), but we had known and met a lot of those faces and people. I sincerely think that it was our most innocent film yet. We didn’t know how markets in Bombay work, so we wrote the kind of film we really wanted to make. After so long in Bollywood, I don’t think we’d be able to make such a “free” film again.

But they say that the Hindi film industry is waking up to new voices and new kinds of films. Would it still be harder to make that kind of film?

Even if I personally wouldn’t be able to, I’m sure such films can be made today. I don’t think it’d be harder than earlier. But it’s becoming tougher for small films because of huge marketing costs involved. The mainstream folks still do manage to make bigger films that are a little unconventional with content and form. They subvert a lot of mainstream formulas, but we’re still not in the same league as the Marathi film industry.

So our fundamentals haven’t changed?

I think so. The trend is the same: three films of a certain kind do well, then one flops, and there is a change of formula. This cycle keeps repeating itself. Black Friday, Dil Dosti Etc, Manorama Six Feet Under came out, and it felt like things would change and that there was a viable parallel stream for a while. Then again we went back to the same commercial tried-and-tested stuff, before Bheja Fry and a few others changed the financial model. These are the usual phases that the industry goes through. Most dawns are false, but there’s still a little hope every year.

The crew for Dil Dosti must have been small, given you all were not from Bombay. How did you manage?

I was also the associate director on the film, and was responsible for casting. Even after Dil Dosti, I’ve always been the kind who likes to be completely involved in a film after writing. I’m no longer an associate, but I’m involved right from the casting to the shoot to the edit process. It depends on a lot on your rapport with the director eventually. This is something I’ve learned to do over the years, which is why I’m fairly respected in my capacity as a collaborator. I’ve heard things about how poor writers never find out what happens to their script after they finish, but that doesn’t happen to me.

And you did Fast Forward after that. Sounds like a very different experience from Dil Dosti…

I came in at the last moment. They were going on floor, but they weren’t happy with the dialogues. I came in to write the lines. We changed the dialogues, I wrote a few scenes accordingly. So I wasn’t really involved from the conception stage. But the experience was good, what with it being a masala film…

I think that’s perhaps your most masala project so far?

Yes. Have you seen the film?

No, I tried to find it though.

Thought as much. Nobody has seen the film. (laughs) It was actually not a bad film. It didn’t get a good release. We needed to do it with stars, because audiences go to smaller films with a different set of expectations. It took one-and-a-half years to release, and it was a dance film. Back then, not a lot of dance films came out, so people were already a bit circumspect. But I’m proud of that film for what it was.

Where did the idea of Sixteen come from?

The idea belonged to Raj Purohit, the director of the film. He had done a series called School Days in Delhi in the late 1990s; it was a huge pop-culture thing back then. When we met, he mentioned that he had directed a lot of school kids during his time in Delhi, and I had my own interactions with kids around the same age. We were familiar with how they were evolving and behaving, which was different from the way we were at age 16. So we thought it was a good and relevant film to make.

You mention that you grew up in the world of Dil Dosti Etc. So was Sixteen essentially an outsider’s look into the world of a 16-year old? Is it more challenging that way?

It can work either way. When you grow up in a certain world, things become slightly easy to capture and reproduce on celluloid. But it all depends on an ability to get into your character’s head, no matter where he/she is from. To see things through their eyes. You can even start with a vague understanding of their surroundings. But if you know them well, the environment sort of takes shape around them, and authenticity and detailing begins to define itself. There’s always a bit of research, but you must know the mind inside those faces completely.

There are very few coming-of-age college/school films in India compared to, say, Hollywood. Why do you think that is the case?

I’m not quite sure. It could be a casting issue, because it’s tough to find competent and ‘starry’ teenagers to carry an entire movie. It’s not exactly an early choice of career for them. But again, if one such film hits the jackpot, you could just see a flurry of them hit the market. Over the last few years, everyone I meet wants a ‘youth’ film, but it’s a little difficult to pinpoint what aspect of youth they mean. In such a diverse country, youth could mean anything, none of which is really portrayed sensitively on screen.

Even Dil Dosti and Sixteen sounded and looked different, and it felt like it was your voice coming through rather than how it really was. Do you think you can look at Sixteen a little more objectively now?

I actually don’t watch my films after they release. Every time you see it, you have a different feeling about it, and find new flaws and mistakes. The general reaction of “what the hell was I thinking?” is common, and it’s really not easy to revisit old work. So it’s hard to answer your question now, given that I haven’t been able to re-watch it — and form evolving opinions about it — since its release.

How did Issaq happen?

Manish Tiwary and his wife Padmaja were writing the script, and I got involved. The basic idea was to focus on Romeo and Juliet; Manish is from Benaras, so he wanted to explore his own world. It’s always interesting when great literature is set against contemporary, relevant environments.

What do you think went wrong with the film?

More than one thing, obviously, but I don’t think it will be professional of me to talk about it. But there were clear mistakes. We’ve moved on.

You take a while between films. So what do you do apart from writing?

In fact, I only write — and I take a lot of time to write. That explains the long gap (laughs). There’s nothing else I do. I do a bit of advertising here and there, but no television or anything.

What are you working on next?

A few exciting projects — a biopic and some other things. But they haven’t reached a stage where I can talk about them. They are in a different space from Sixteen though. I’m growing more ambitious as a writer. Definitely an exciting time for me.

Do you find yourself attracted to certain kind of scripts or ideas?

At one level, all my films have been friendship-oriented. This happens sub-consciously; not like I decided to do a female buddy flick just because I did a male one. Love, and its ambiguous natures, as well as death, are other recurring themes: the whole slightly less conventional initial attraction-to-love phase. You only look back and realise this, and not while you’re working on them. A lot of times you recognise this after reading particular reviews, too.

Any writer you admire or have been influenced by?

On a personal level, I’ve been influenced by a lot novelists instead of screenwriters — like John Irving, Salman Rushdie, Ben Elton, who’re some I really look up to. I come from a literary background, and I’ve always been a heavy reader. I strive to imbibe literary qualities in my work.

Maybe that’s why your films are pretty character-heavy?

Yes, probably. Characters are the most important things; they’re what drive your films to the end. The greatest action and song sequences may not make sense even individually if you don’t care for those faces involved.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.