Documentary: Death Of A Gentleman

Trailer:

In 2011, two young journalists set out to make a documentary on the love of their lives — the game of cricket. Jarrod Kimber, who many of you will now recognise to be a very popular Cricinfo contributor, and Sam Collins, the web editor of thewisdencricketer.com — both purists and lifelong fans — joined forces in order to explore a rather numbing transformation of cricket. They wanted to find out the reason — if there was any — why the oldest format of the game, test cricket, seemed to be in a state of decline. For them, this demise may have not existed, but they couldn’t ignore certain trends: T20 and franchise cricket had exploded onto the scene, India had just won the ODI World Cup and were about to be thrammed senseless in test matches, while three major countries (India, Australia and England) seem to have been playing far more cricket than other nations. There had to be some connection.

So they became detectives, the kind who really hoped not to find anything wrong. But what they found over the next two years shook their faith in far more than just the game.

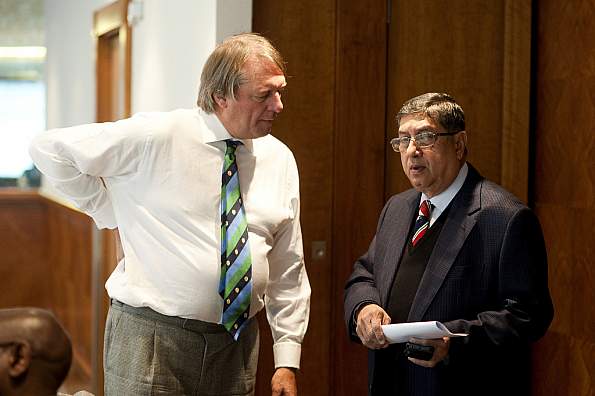

Collins (L); Kimber (R)

‘Death of a Gentleman’ is a startling chronicle of events many fans are vaguely aware of, but never bothered to really explore. These two obsessive journalists took it upon them to diagnose the game, and started by joining their friend Ed Cowan — a long-time Australian domestic cricketer — who was making his test debut against India on Boxing Day, Melbourne. They wanted to share Cowan’s childhood dream, and recognise why exactly test cricket meant the world to him. And to them. Australia won the series 4-0, and Cowan, at 28, was at the cusp of a long career. All was good.

Soon after, murky events started dotting the administrative landscape. For some reason, the BCCI, ECB and CA, three of the “daddy” cricket boards, began bullying the ICC. In fact, they wanted to *become* the ICC — by proposing that a large chunk of TV rights went to just them, and the rest would be distributed scarcely among the other “smaller” nations. This meant that these 3 countries — and primarily, the BCCI, considering their IPL stake and the fact that their Chairman N. Srinivasan was also the Chairman of the ICC now — would control World Cricket, schedules, finances, and the general life of the cricket fan. Kimber and Collins spend two years in this documentary trying to make sense of why this “villainous nexus” is taking place. They also explore the ‘Big 3’ rejection of the famous Lord Woolf report, the rejection of cricket as an Olympic Sport (which, in turn, prevents smaller and associate nations from playing the game professionally), the impeachment and eventual whistle-blowing ways of Lalit Modi, and the 2014 “secret” Dubai meeting that decided to hand over reigns to the bullies.

They didn’t quite reach the stage where a newly-reformed ICC, led by Shashank Manohar, scrapped this arrangement in favour of balanced and independent governance in early 2016.

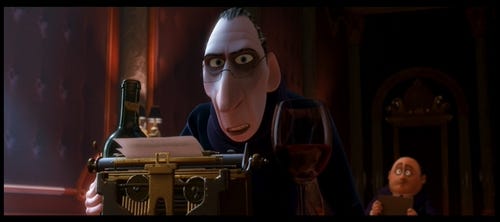

What the makers do is present everything you have ever read in newspapers in a coherent and elegant manner. They dramatize it like they would, a real film, and pinpoint events with the limited penetration usually awarded to snooping conspiracy theorists. By using Cowan’s career as a simultaneous metaphor for the decline of the “gentleman’s game”, the film doesn’t hide its romanticism and dryly presents its one-sided and sincere pursuit of the truth. Most of their interviews are self-explanatory, especially the ones with Srinivasan and ECB Chairman Giles Clarke; they deflect, lie, go on auto-pilot, lose their cool, get arrogant, defensive, cocky, embrace the next-question-please mode and generally look like men out to get away with a crime. Or at least, that’s how “moral cops” Kimber and Collins are treated — like nosy journalists who’re crossing the line time and again. By the end, they’re the ones made to feel like criminals, which says a lot about the general functioning of powerful profiteers.

Clarke (L); Srinivasan (R)

All through, though, the makers’ — as they put it — “become a part of a ’70s paranoia movie.” They track down discrepancies and are ignored and humiliated by their own kind, but somehow manage to get just enough change-of-heart voices to speak on camera. Everybody knows it, but nobody wants to talk about it. Their general mood can be captured by this one evocative scene: Cowan’s wife, in the stands, watches nervously as the stodgy batsman approaches his maiden test century in Durban. This is 6 months in the making; he wants it, he deserves it. He pulls a ball, and there it is. Mrs. Cowan, meanwhile, her hands covering her mouth, watches silently, enjoying her own personal little space at the back of a stand. The camera focuses on her — speechless, almost trembling, recognising this culmination of the many struggles and sacrifices they have have undertaken as a family over a decade. She doesn’t cheer, doesn’t scream, she just watches — nobody in particular. She watches as a man finally realises his dream.

This is the beauty of test cricket — it feels heavier, and feels more important and precious. This is a moment that many athletes live for; they strive to experience it in many sporting arenas, the purest form of what they set out to achieve. It is, both, a personal and public moment, with entertainment and feeling derived out of the fact that its intimacy is actually a shared virtue. Kimber and Collins recognise this moment, and they love watching it. We all do. It’s the backstory, the build-up that matters. This isn’t a moment that can be created by design, which is what the Srinivasans and the Clarkes are out to do. They, too, believe in the purity of these moments, and they probably tear up while watching it too, but they then set out to artificially recreate as many of these moments as possible, on their own terms. The sanctity of the moment doesn’t feel the same with a maiden IPL century, or a successful auction, or a test win on home soil. It can only happen with maiden test centuries, away wins, World Cup wins…the “big” ones. No matter who you are and where you come from, there’s an underdoggedness to this moment. These days, however, it’s nothing more than a fleeting second of success. Somewhere along the line, according to Kimber and Collins, the administrators have lost sight of why they got into managing the game; they’ve lost sight of the fact that scripts cannot be written.

And they’re right. Their documentary becomes more of a campaign by the end — as demonstrated by its website and petitions. Perhaps they know that not much will change, and that moving backward is now the only form of evolution. In any case, to experience their dismay, and to wake up and recognise that not all we see on TV screens is pure and ‘free-spirited’ anymore, ‘Death Of A Gentleman’ is a timely watch.

(Available for viewing on TVFPlay for Rs. 99)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.