By RAHUL DESAI

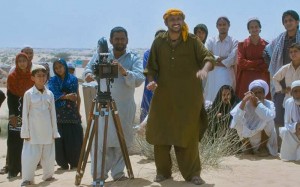

A week after a film named Filmistaan released in 2014, I met Inaamulhaq at a coffee shop in Versova.

I didn’t know the guy; I had just seen him in this little film that had garnered generally positive reviews. It was therefore odd that he sought out the one mainstream critic who hadn’t rated the film very highly. He was interested to learn that I was doubly disappointed by the film’s tepid final act after a thoroughly entertaining setup. “There’s nothing more tragic than a vibrant satire losing its way,” I had concluded, rather mournfully.

But he was actually worried about something else.

“Can you tell your newspaper to do a piece on me?”

I got wary – oh no, not this again. I’m a critic, not a reporter.

“No, no, not a vanity piece. I’m happy for the film and all, but there’s a problem.”

He shifted in his seat, not knowing how to present his bittersweet predicament without sounding absurd.

He thinks – and writes, as I later learn – in chaste Hindi. So he rattles off his situation, and I couldn’t help but note how similar he seemed to his sweet, passionate, film-pirating character, Aftaab from the film. A bit antsy, a bit distracted, bursting with nervous energy. I mentally congratulated director Nitin Kakkar for casting this man.

“You see, I’m not being offered any film roles.”

That’s perfectly normal, I thought. Good actors are rarely offered the roles they deserve.

“…because of my character Aftaab, the Pakistani Bollywood buff who helps the protagonist (Sharib Hashmi). All the directors here think I’m a Pakistani actor. They think I’ll have visa issues.”

It took me a millisecond to realize that he was serious. And another second to realize that, somewhere, deep in my consciousness, I too had assumed – while watching the quirky film’s events unfold – that he came from the other side of the border.

So here was an actor who was perhaps so convincing…that it had begun to work against him.

I told him to be patient, and perhaps hire a PR agent to push this well-meaning ‘correction’ to various publications. I felt a bit sad that I couldn’t help him at that point – considering he had waited two years for Filmistaan to get made and then secure a limited commercial release in theatres.

To be fair, it did arrest a lot of attention within the circle. He sounded even more excited when he spoke about how gracious and full of praise Vidhu Vinod Chopra was about their little effort. He always seemed like the kind of artiste who aches to use his hands to make swaying gestures, but was probably told by someone early in his career not to.

“He called us to his office and told us he’d do anything to help. Who does that these days?” he exclaimed, with a twinkle in his eye.

When I looked up the film on the internet to read some more reviews, I was happy to learn that Filmistaan had won the National Award for the ‘Best Hindi Film’ a year ago. I hoped, sincerely, that Inaam would play his cards right. Especially after seeing its lead actor, Sharib Hashmi, in an utterly unforgettable flick called Badmashiyaan later that year.

That’s the thing about being a reviewer day in and day out. When you spot a spark, or a potentially decent new face out of nowhere, you feel like doing more than just compliment them. You feel like doing more than just reaching out. That evening in 2014, I felt a little helpless, but also quite confident that this bubbly little man would find his place under the sun. It was just a matter of time.

I wasn’t wrong.

After a relatively quiet 2015, I had assumed that he had perhaps gone full throttle on his day job of television writing. (“Even here, I don’t sell my soul anymore. I can’t afford to. I write in the children’s space; things that I can look back on later with no shame.”)

And to my pleasant surprise, like most unconventional faces, he popped out once again from the wilderness – as the evil, theatrical Iraqi Major in Akshay Kumar starrer Airlift.

Not surprisingly, he was part of the year’s first acclaimed film.

There is a bit of Colonel Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz in Inglorious Basterds) in Major Khalaf bin Zayd – the power-drunk hustler, who assumes greater importance than is assigned to him by Saddam Hussein (who is never seen, but his power is sensed).

Like Landa, he is in his own little battle bubble – as if he were able to examine how deliberate he behaves only to make his victims squirm. The similarities don’t stop here. He even attempts to cut his own sweet deal with Kumar’s businessman character during Iraq’s brutal ransacking of Kuwait. He doesn’t quite care for the war much – always seen outside the line of fire, within the confines of large, creepy mansions assumedly barking orders to his rowdy soldiers.

“He is just a greedy chap looking to make a quick buck”, Inaamulhaq explains – as we sit down at another coffee shop in Andheri, days after Airlift hits screens.

“But I consciously based my act a bit on Saddam’s oldest son, Uday Hussein, or at least the way he has been portrayed in The Devil’s Double and a few documentaries. I read up a lot about the war, and zeroed down on his eccentric, flamboyant persona.”

Many viewers have lapped up his outlandish Hindi accent, especially because his counterpart is a subdued, sober un-Akshay-ish superstar, who reins it in to provide a stark hero-v/s-villain contrast.

“It was so easy to go wrong and become a hamming caricature; a tight rope I walked. Admittedly, for some, I fell from that rope,” he chuckles, remembering that film critic Mayank Shekhar referred to him as “an Andheri actor” in his review. “Remind me to ask him what that means if we ever meet.”

I assure him it’s not that bad a thing.

The fine actors, those who have created a niche for themselves in mainstream Hindi cinema over the years, now reside in the burbs, mostly around Andheri. As if on cue, he mentions the now-famous likes of Nawazuddin Siddiqui and Manoj Bajpayee – as senior contemporaries whose space he would like to co-inhabit.

He is still shifty, still restless, and is on a high only artistes whose work is thrown at the mercy of the world will understand. He resists the urge to check his phone for the hundreds of Twitter mentions and congratulatory texts. For now, he can only find solace in the vibrations of the constantly beeping device.

“You won’t believe where I’m coming from,” he says, breathlessly, not waiting for me to make a wild guess. “I haven’t had the time to enjoy all the attention yet because…I’m in the middle of writing a TV pilot episode!”

I wince.

“No, I can’t back out. It’s a commitment, and also, it puts food on the table. It always has.” he answers, in prompt response to my sympathetic gaze.

“I try to write for serials that aren’t your usual run-of-the-mill soaps. It’s very easy to get sucked into the TV-writing culture though. The money is obscene. I was once a creative consultant for The Great Indian Comedy Show, being paid upto Rs. 3 lakhs a month. I had almost reached a point of no return. That kind of money is addictive. I had to remind myself that I’m here to become an actor – and I left everything to find a better balance.”

He admits that it simply isn’t feasible to be a struggling actor in Mumbai. A day job, or inheritance of any sort, is a must.

“It’s what kept me from taking up silly bit roles after Filmistaan. If I had nothing else but acting, I’d have agreed to everything in desperation. I can’t blame those who do. Survival is difficult. Fortunately, having a family – a wife and a 5-year old son – has tempered my idealism.”

This sort of explains why he wasn’t seen on screen for more than 20 months, despite winning 5 ‘Supporting Actor’ trophies (“There’s no space for them in my 1-BHK!”)

“It’s not that I’m choosy. Fortunately, being a writer, I have a sense of identifying solid scripts. I knew when I was being conned, or when the filmmakers could back their words with true vision.”

For some reason, he had trusted Raja Krishna Menon almost impulsively.

But they met in peculiar circumstances – where Inaam was a writer pitching his script to Menon, the director. Some time later, after Menon watched Filmistaan, he was convinced that whenever he’d make his next movie (after Baarah Aana), Inaam would be a part of his vision.

“Perhaps it was meant to be. When he approached me for Airlift, I was back home in Sahranpur (Uttar Pradesh) mourning the death of my father. I told him to carry on. I had no idea when I’d be back. But he waited for me – he waited for his villain – for a month, till I came back to Mumbai.”

He didn’t need to, but Inaam believed that he owed Menon an audition, a glimpse at what he was in for.

“I had to show him if he was right or wrong to choose me. I asked for a few days to prepare. I didn’t want him to make a big mistake.”

It’s 2016 now. Only a few hours ago, Inaamulhaq had experienced a heady feeling most upcoming actors live for.

He was recognised by a random bunch of moviegoers outside a multiplex. “My friend suggested I should wear Major’s fake moustache so that this happens more often. No way I’d do that. What’s wrong with this face?”

Like countless other aspiring actors, he had once stood outside Mumbai’s VT Station back in 2000, fresh from the National School Of Drama.

And like many, his backstory is an underdog film on its own. Only, he doesn’t care if people know that. In fact, he prefers they don’t. It doesn’t matter where you’ve come from, he repeats through the evening – because the audience doesn’t (and shouldn’t) care either.

“I didn’t like the fact that the media went to town with the whole Nawaz-being-a-watchman angle. Everyone has his/her own struggles. Everyone’s path to fame is different. It’s almost disrespectful to Nawaz, the performer, that he is looked at through the poverty-porn lens. It’s almost like they want people to remember his poor beginnings whenever they see him shine on screen…” he trails off.

Evidently, he hasn’t had a happy relationship with the fickle shores of entertainment journalism. He rightly points out that his own background isn’t mentioned anywhere – though, suddenly, some mainstream publications are exhibiting immense interest in him today. The same ones had rejected to print a word about him not too long ago. But he also can understand that they will turn the way the tide flows.

Before we get into the murky Media-Net discussion, I steer things into flashback mode. I know he’s not the type to exploit his difficult childhood for a role. “Maybe at the end of my career, while writing a memoir, it’s fine to reflect on the details. It was pretty straightforward otherwise. Being from an orthodox Muslim family, it came as a shock to my folks that I spent my time rehearsing for plays instead of taking typing class – the norm back then.”

You can almost imagine Inaam’s childlike enthusiasm, in tact even today, refusing to be stomped out by traditions. He is God-fearing, he is religious, but not in a way that would interrupt his progress. “Only when the local papers mentioned my admission into NSD, things changed. It was a prestigious thing for a small town. Yeh ladke mein jaan hai, josh hai, they thought.”

But the acceptance rarely mattered when he found himself stuck in the deepest, darkest ruts of B-town.

He has no qualms admitting that he was one of the writers of Ramgopal Varma’s Not A Love Story, for which he wasn’t given credit.

I’m amazed that he speaks about it with a cheeky grin. Maybe it wasn’t too funny when it was happening. The power of hindsight, of course, does wonders.

“There’s this thing we call the ‘RGV-tax’ here. For every person he screws over, he also returns the favour. For example, I got the dialogue-writing gig for Buddha Hoga Tera Baap through him. And this is consistent. Every newcomer pays this RGV tax – like an unofficial industry-integration exam.”

As we walk out towards the parking lot, he points out to a newer, bigger car.

“I’ve graduated a bit, as you can see,” he smirks. “But the basics remain the same.”

He goes on to speak proudly about how he has enrolled his child into an International School without a syllabus and exams – a practical, viable alternative to the one-dimensional Indian education system. I find myself nodding vehemently. We discover that our artistic careers are, perversely, results of an inherent disillusionment with the mug-happy courses we pursued (Science), and its lack of relevance in everyday lives.

“I don’t want my child to go through the same nonsense,” he remarks, grudgingly courting the irony that he writes for a living now. He too believes that education, these days, is a state of mind.

As I catch him sneaking a peak at the Airlift billboard above him, I finally ask him the question I had scheduled this meeting for.

“How does it feel to watch your performance with your family? Your friends? It must be awkward…”

He almost blushes. He knew this was coming. And he knows what he feels about this.

“Well, my friends liked it. I’ve watched many shows with them.”

He leans on his car, carefully measuring what he is going to say next.

“But my wife…”

Here it comes.

“My wife says it that my ‘acting’ was too visible. You see, you have to understand…” he smiles that infectious smile, the kind a narrator flashes when he is about to rock a punch line. “At home, she isn’t used to seeing me frighten people. I am usually the one being frightened…by her!”

I bid him goodbye; he watches as I struggle through heavy traffic to reach the other side. “It’s funny how rickshaws slow down and hinder your progress just as you are about to cross a road. So much like life.” he laughs, before driving away into the sea of red braking lights and bumpers.

There is much truth to this parting shot. Hopefully, it won’t take another 20 months before I find myself introspecting over his anecdotes.

(Chidiya, the next script that has chosen him, is a children’s film. You can look at his website here.)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.