By RAHUL DESAI

Director: Ryan Coogler

Cast: Michael B. Jordan, Sylvester Stallone

In ‘Rocky Balboa’ (2006), a film widely considered as the more official and appropriate series concluder than the utterly negligent ‘Rocky V’, Robert Balboa – Rocky’s son and ‘heir inapparent’ – is a white-collared yuppie determined to escape his father’s considerable shadow. Till he can afford to leave the city and pursue a career somewhere else (a move that is incidentally hinted at, in CREED), Robert considers his family name to be a liability of sorts. He becomes a corporate slave by choice; it’s perhaps the most logical way he can distance himself from the champ’s overbearing legacy. The film that encapsulates his second-hand struggle is only a sweet, endearing, good-humored extension of the Rocky legend; it respects timelines, and comes very close to disrespecting time itself, by letting a tragic 60-year old widower enter the ring for one last hurrah.

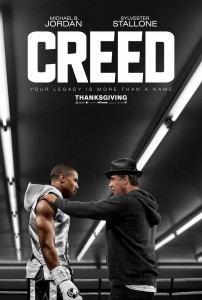

‘Creed’, at least in context of the now 69-year old Stallone, respects time and mortality far more. However, this ex-champion and harbinger of underdog greatness is almost incidental to this particular story. This isn’t about Rocky Balboa, yet it is about a man who lives his life.

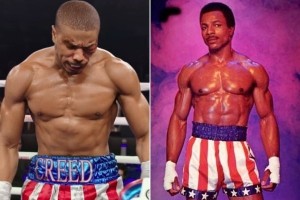

It begins with one Adonis Creed (Michael B. Jordan), the illegitimate son of Rocky’s deceased friend and former rival/champion Apollo Creed, in this ‘Robert phase’ of denial. He works at a desk, but unlike Balboa’s son – who perhaps mutes out his inherent fighting DNA in his surge of rebellion – Adonis acknowledges his destiny. He doesn’t fight it; instead, he fights, and nurtures a secret pro-career on weekends in Mexico. Because, unlike Robert, Adonis never knew his father, and therefore, has nobody in particular to run away from. He hates Apollo for human reasons, but loves him for boxing reasons. It is in his genes.

Only, he emulates Junior Balboa in his desire to step out of these broadening shadows, to create his own chapter – which is why he goes by the name of Adonis Johnson – and legacy in the very same arena. This is arguably far more difficult to accomplish. Ask a certain Rohan Gavaskar or Abhishek Bachchan; they’d tell you all about how a famous last name is a double-edged sword. Adonis knows that even if the name gives him easy access, it won’t give him an independent identity. Once his surname becomes public knowledge, he will not be able to hide from it.

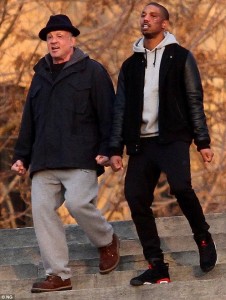

This, in a nutshell, is what Creed is really about – a young fighter with daddy issues, who chooses instead to adopt the life of his hero and ‘uncle’ Rocky Balboa (the only boxer to defeat his father) in spirit, tenacity and graph.

As fighters, they’re on opposite sides of the spectrum, but as men, Adonis wants to be on Rocky’s side. He doesn’t really need to idolize someone like Balboa; it’s like AB de Villiers clutching onto Rahul Dravid for inspiration. He is probably far more talented and gifted than Balboa once was, and signifies everything that Balboa didn’t: speed, depth, skill, rhythm, agility and swagger. In short, he has inherited all that Apollo represented, but doesn’t want to be him. And so he hangs onto Balboa not so much for the game as its disciplines, and the less magical aspects of the game, in an effort to become a perfect amalgamation of Apollo and Rocky – the dream warrior. At this rookie stage of his career, his success will explain why polar opposites like Djokovic and Boris Becker form a good tennis partnership, or why even Apollo was such a crucial addition to Rocky’s coaching staff after Mickey’s death.

Somewhere during the two-plus hours of Creed, nostalgia and wistful smiles give way to unfamiliar, original emotions – feelings that one doesn’t usually associate with watching a franchise spinoff. The symbolic training montage invokes, for once, not the ‘eye of the tiger’, but the modern, chest-thumping sounds of a cub let loose in the wild. The crescendo-specific conclusion of the adrenaline-fueled crack-of-dawn street-sprint doesn’t occur at the top of the iconic 72 stone steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; a circle of wheelie-whirling mean bikers surround the heir apparent instead, as he roars out to the real, less-than-statuesque, withering Balboa peering out through his bedroom window. The much-hallowed ‘heavyweight’ category is replaced by the more practical and revered pound-for-pound status. The villain is not quite a villain either – a top-ranked Liverpool working-class hero, who is on the verge of a life crisis himself.

Paulie is dead, Adrian is dead, Robert is far away, and Rocky is desperately, quietly looking for reasons to live and exist. He is, in fact, the same age (69) that actor Burgess Meredith was when he played Mickey – the grumpy, crass gym trainer who Rocky stalked and harassed into coaching, 40 years ago. Adonis stalks Rocky too, and convinces him to become the battle he lacks. He knows that he has had a more privileged upbringing than most in his field – after stumbling through foster homes, he is raised by Apollo’s wealthy and generous widow – and thus needs Rocky to simulate for him that illusion of hardship, difficulties, trouble and challenges. Rocky is his dark shadow, the crippling reminder of reality he must wake up to every morning.

On the way, he falls for his neighbour – an attractive, sexy singer with her own reasons to ‘seize the moment’. Like Adrian, she will cheer for him, but it’s difficult to imagine the same kind of loyalty, love and commitment between them in this day and age. I wouldn’t be surprised to see Mr. Jordan wooing another woman in his next outing as Baby Creed – though I’d like to believe that his Uncle Balboa would berate him for doing so.

Yet, if you look back, this journey feels familiar, the rise looks inevitable, and the life beats are recognizable. This film takes us hurtling down the same path, without quite letting on that this is actually a skilful, visceral reboot of the 1976 story.

It takes Rocky’s legend forward by finally ending it, and recreating it in a more likely, contemporary environment. Rocky exists here, but you’d be forgiven for hoping he didn’t. Nobody wants to see time and health take its toll on heroes. Nobody wants to see them as human, frail and soft as Rocky becomes. But this is necessary; it is necessary for Adonis to see this, and it is necessary for us to recognize that Rocky is not forever. He shouldn’t be, especially in this era of repetition, remakes, reactions and remembrance.

Director Ryan Coogler, whose first (and previous) film was a Sundance indie darling, the biographical ‘Fruitvale Station’, reminds us that a franchise film need not fully rely on its inheritance. Even if another face symbolizes the same tale, it could work. It can be a showcase of good filmmaking too – a platform for craft, grammar, style and technique – which could set it apart from an equally predictable ‘Southpaw’, or a texture-heavy ‘Cinderella Man’, or a tone-heavy ‘Million Dollar Baby’. He teases with background score cues, constantly dropping in heroic strands of ‘Gonna Fly Now’, before belting out its post-modern hip-hop interpretation.

He knows that cinematic fights revel in their lack of respect for physics, technicality and endurance (any real boxer would have been killed if they had copped half of Rocky’s punishment), and puts immense soul and humility into the brutality meted out to Adonis’ rookie strides. He plonks the camera into the ring in a kinetic, spasmodic Wrestler-meets-Black-Swan-isque fashion, giving us the more memorable on-screen boxing bouts in recent memory – certainly far more compelling than the recent Mayweather-Pacquiao title bout.

But Coogler’s most remarkable achievement is something that goes beyond merely making this fictitious universe come full circle. It goes beyond Rocky finally finding someone to pass on his baton to, and beyond being able to create a film that acknowledges the importance of energy in clichés.

Coogler manages to make life come full circle too.

This, in every way, is its own film, and yet, 40 years after the founding film’s Oscar success, it hands old Sylvester Stallone a real shot at a ‘supporting actor’ nomination. For being Rocky Balboa in his own franchise, but in a movie that doesn’t star him, and isn’t written by him; hell, it doesn’t have him in its title.

Who’d have thunk it?

(Director Ryan Coogler is 29 years old. Furthermore, a fair amount of melodrama and tragedy is involved at the precise moment I discover that he was born a month after me)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.